This is Section 6 of a series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

“Order and simplification are the first steps towards mastery of a subject.”

― Thomas Mann (1875-1955)

Section 6. Determining the Proficiencies

Introduction

Quite unlike any other social institution, universities are charged with ensuring that the most people possible gain the greatest benefits from their expert knowledge, research capabilities and innovations. It is not a burden to be underestimated or sidestepped in any way; it remains a seminal part of any university’s DNA.

The opening five parts of this series have laid out the multidimensional approach required to achieve this goal and derive impact from universities. We have established and framed the need for universities to identify and attract potential partners with whom they can work in addressing societal needs, and we have explored the far-reaching complexities involved in shaping engagements that benefit universities, their prospective partners and our communities.

Section 6 of the series now considers the specific university activities that must be carried out in-house to reach these lofty and worthy goals, activities underwritten by a masterful command or unequivocal expertise, without which universities cannot effectively manage the exchanges that ultimately lead to societal benefits.

Now comes the point in the process where a university must examine the nature of the expertise within its walls and ask ‘how do we get this done, what do we need to be good at?’ Now comes the point where a new order is placed on proceedings, a crucial act of determination that ultimately informs and guides how a university operationalises its organisational direction. Now comes the point where a university must identify its critical proficiencies.

Identifying critical proficiencies

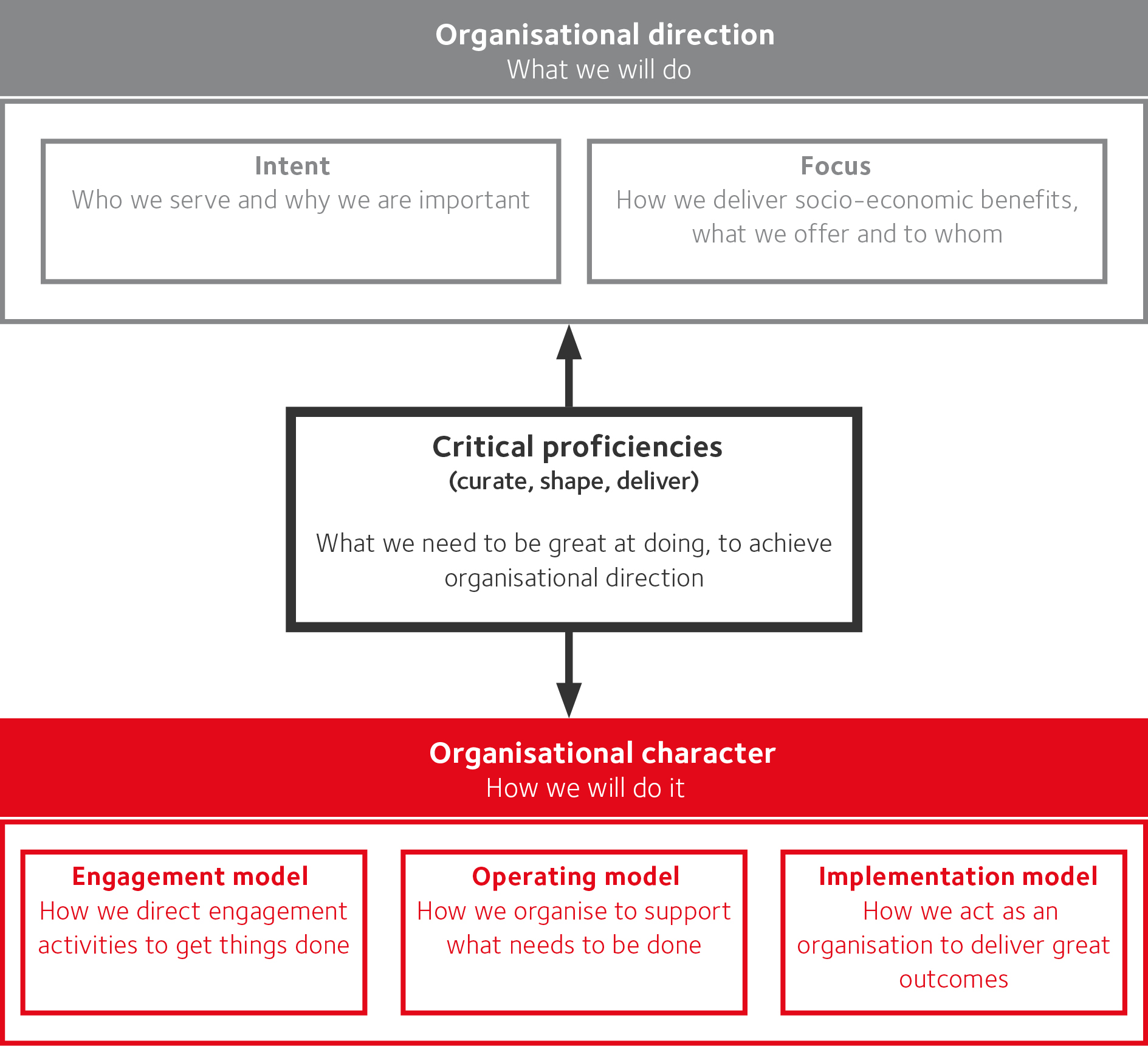

Earlier sections of this series explained the roles of ‘intent’ and ‘focus’ when setting organisational direction for universities. Establishing ‘intent’ is critical and involves two components; viz., a clear understanding of major trends and demographic shifts (see the ‘North Stars’); and the articulation of purpose (see ‘Spheres of Impact’). Determining ‘focus’ is equally critical and involves the development of a well-honed framework to optimise the delivery of socio-economic benefits (see ‘Understanding the Knowledge-Capital Value Chain’) and in light of that, discerning a spectrum of opportunities universities should pursue (see ‘Opportunity Spectrum’). Intent and focus are especially important when operating in dynamic and competitive environments as they help catalyse purposeful action.

The organisational direction which is set through these actions is a necessary condition for a university to thrive. But while it is necessary, in itself it is an insufficient condition. Along with setting organisational direction, careful consideration must also be given to the implementation of organisational direction and aligning various organisational activities so that great outcomes are achieved. Organisational character is required to support the achievement of organisational direction.

How universities get a sense of what is required at this stage starts with identifying those key factors that universities must master to achieve their organisational directions. These factors, can be called ‘critical proficiencies’.

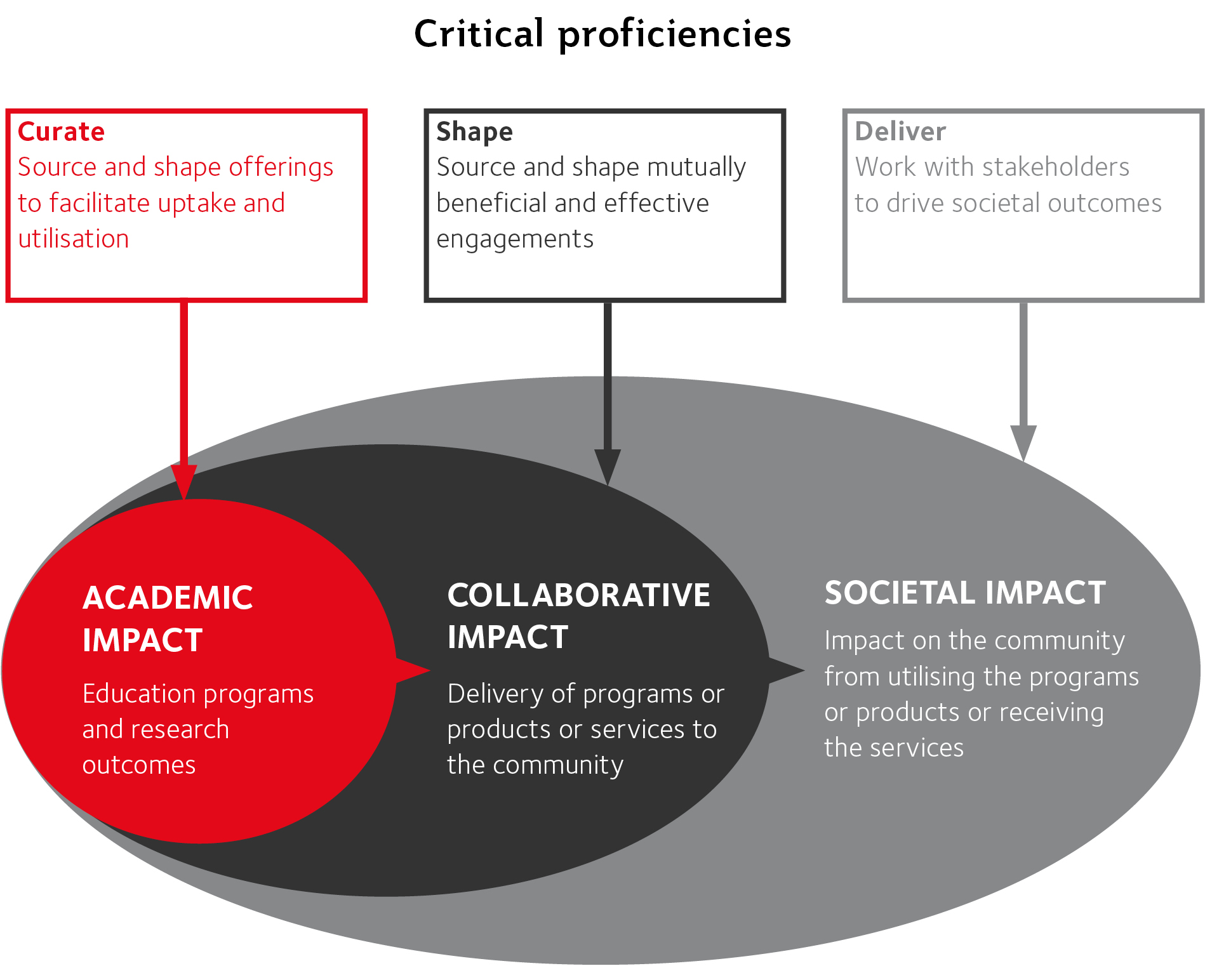

To understand a university’s ‘critical proficiencies’ and why and how they are relevant, it is helpful here to recall the ‘Spheres of Impact’ framework explored earlier in the series. There, it is proposed that to derive impact from universities an outward focus on major societal needs is needed along with an ability to shape education programs and research outcomes to address those needs. To truly ensure our communities derive the greatest socio-economic benefits from each opportunity, it was proposed that collaborations with many other organisations are required. Through the prism of the ‘Spheres of Impact’ framework, it becomes clear that universities deliver great societal impact from their academic impact through collaborative impact.

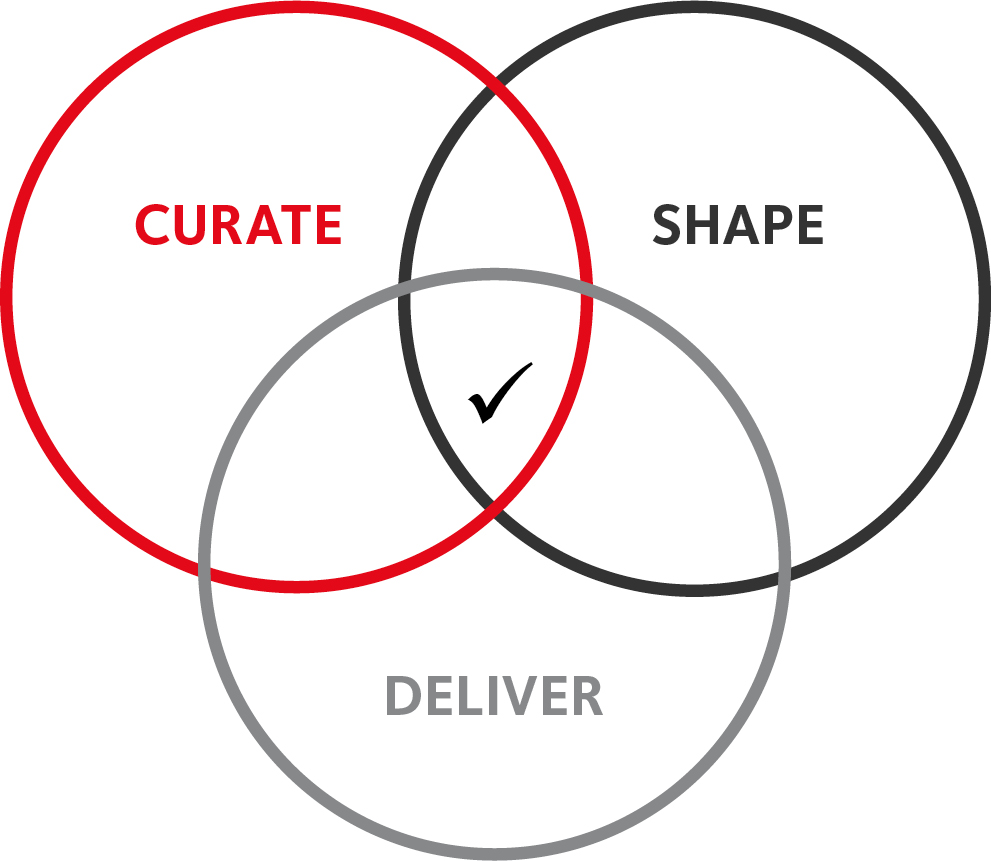

Building on the ‘Spheres of Impact’, it can be asserted that universities must become proficient at curating opportunities, at shaping successful partnerships and at working together with other organisations to deliver benefits. This important operational link between the ‘Spheres of Impact’ framework and the ‘critical proficiencies’ is illustrated below and each proficiency is explored individually in the following sections.

Proficiency 1: ‘Curate’

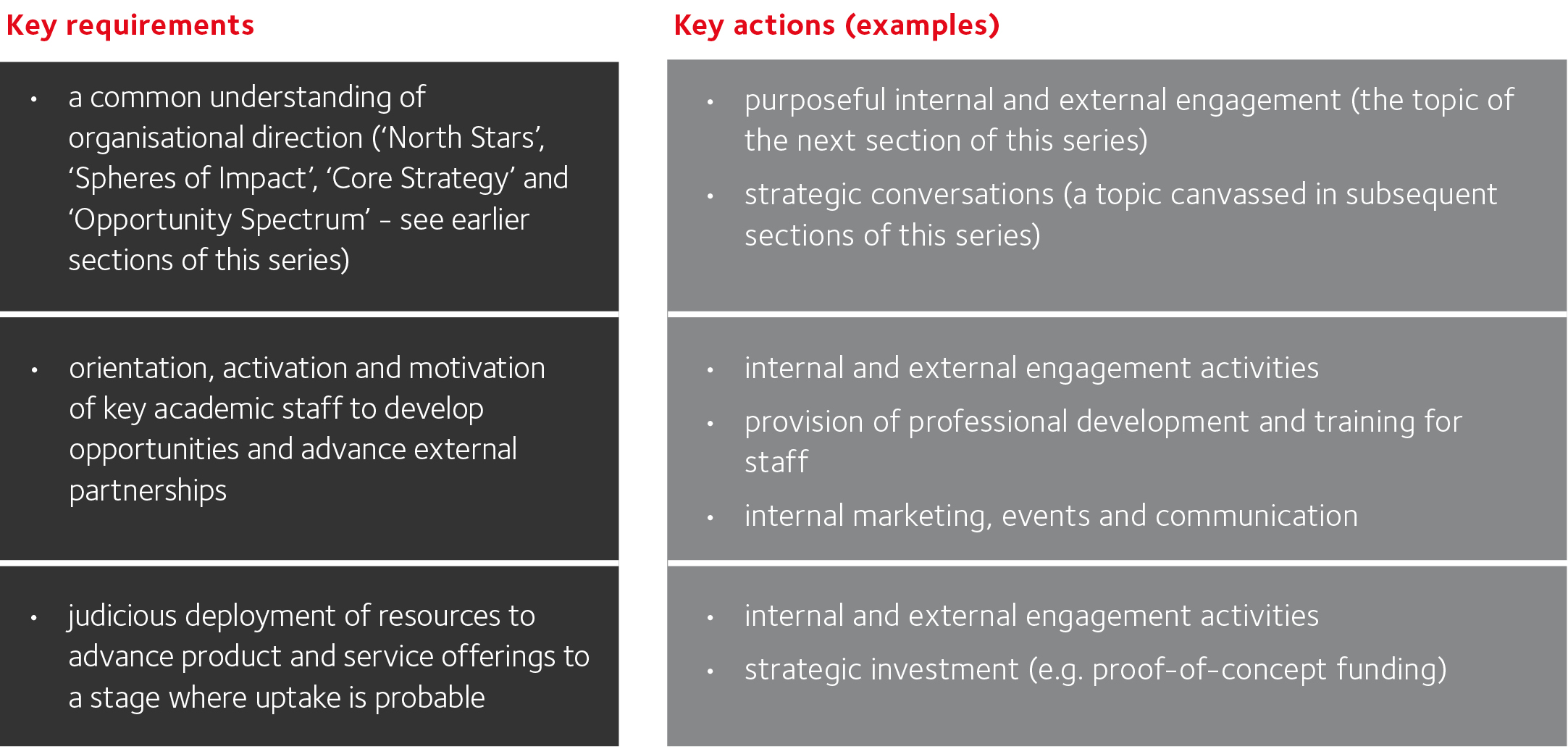

Organisational direction sets the context within which the curation of opportunities occurs. For each ‘north star’ (e.g. the changing natures of workforces, the rise of innovation and entrepreneurship, or societal challenges that require solutions), a university must derive a spectrum of opportunities it can pursue and to which resources can be directed. All universities must therefore become specialists in sourcing, selecting and organising institutional offerings that are likely to facilitate uptake and utilisation by others.

The challenge here is to identify potential or intended outcomes and end-users of scholarship and research early in the process of program and project planning, and then design approaches that maximise the likelihood of translatable outcomes. The key is to target and go after attractive opportunities with competitive offerings through the suitable alignment of associated activities and resources. The outcomes from this alignment are the conversion of knowledge into products and services that, through innovation, make tangible and measurable contributions to social and economic well-being.

In short, by being proficient at curating opportunities, universities can start to successfully derive impact. The following table provides examples of some of the key requirements and activities that a university must master to curate opportunities.

To position offerings competitively, universities must become adept at examining internal environments (e.g. organisational resources such as knowledge, innovations and research capability) and external environments (e.g. markets served, paths-to-markets and competitive landscapes). This examination, which requires purposeful engagement with internal and external stakeholders, is especially pertinent when curating opportunities and is among the examples of key actions listed in the table above. Purposeful engagement is the fulcrum for mobilising resources to deliver profound societal impact and a crucial standalone topic that is discussed in the next section of the series.

Proficiency 2: ‘Shape’

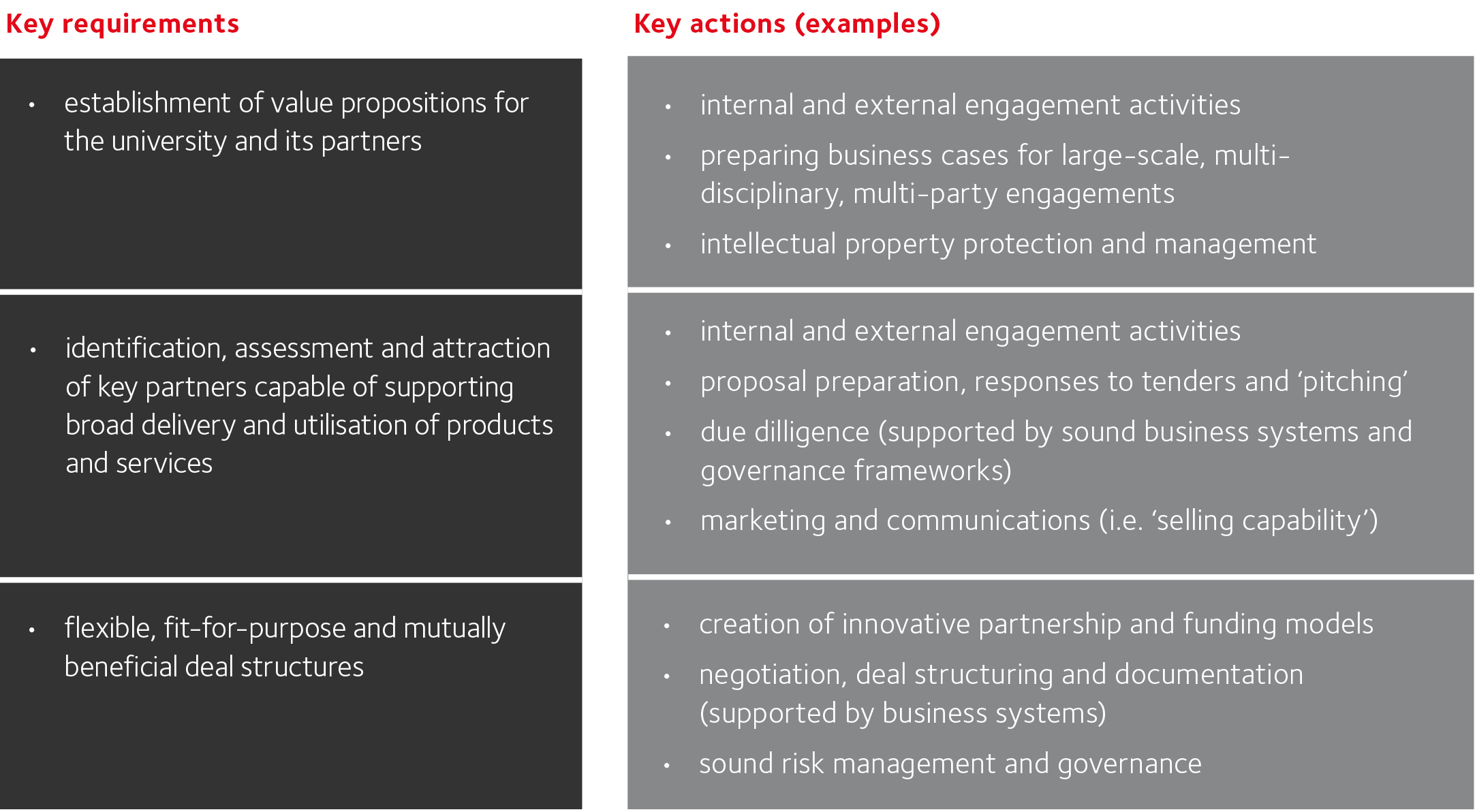

For successful partnerships to occur, universities must be able to initially source potential or likely partners and then establish value propositions for those partners and for themselves. There are three main aspects to this.

First, as universities operate in competitive environments, the value propositions offered to partners must be differentiated or be more valuable than alternatives in the marketplace. Such a value proposition exists when the benefits derived by a partner (which, conversely, are the benefits to be provided by a university) exceed what that partner is required to pay for those benefits (which, conversely, are the funds or consideration to be received by a university for providing the benefits). Typically, there are many external organisations (including other universities) offering bundles of benefits and price points to potential partners. Therefore, the ability to position offerings competitively, often through differentiation, is required on the part of universities.

Second, universities too must benefit from the partnerships, and must be able to do so in the context of competitive environments. The benefits received by a university from a partner (e.g. funds or other forms of consideration) must exceed the cost of providing the benefits (e.g. in the form of products or services) to that partner. If not, a partnership will not be enduring and therefore cannot sustainably deliver societal benefits. Operating in circumstances where universities cannot cover costs or where provision of products or services is too risky means that the likelihood of sustainable social dividend is low. In a competitive environment, an ability to shape offerings that are on economically sound footings, is required on the part of universities.

Third, entering engagements with third parties involves risks to a university. There are risks associated with an engagement itself (e.g. risk of financial loss), but also beyond an engagement and more broadly to a university (e.g. risk of impaired reputation, impacting other university operations). Risks may be mitigated, however, through judicious selection of partners, and the professional management of associated partnership terms and conditions. Universities, therefore, must not only become skilled at positioning competitively and economically, but also be adept at partner selection, articulating the scope of the partnership (i.e. what is to be provided) and negotiating and documenting the associated terms (i.e. the basis upon which provision occurs).

Accordingly, all universities must become proficient at shaping mutually beneficial and effective engagements for socio-economic benefits to materialise sustainably. An exercise in moulding and forging an engagement with a partner, this capacity to shape, is another critical proficiency required by the university if impact is to be derived.

The following table provides examples of some of the key requirements and activities that a university must master to shape enduring engagements. With its stock rising in this context, the need for purposeful engagement is again highlighted here.

Proficiency 3: ‘Deliver’

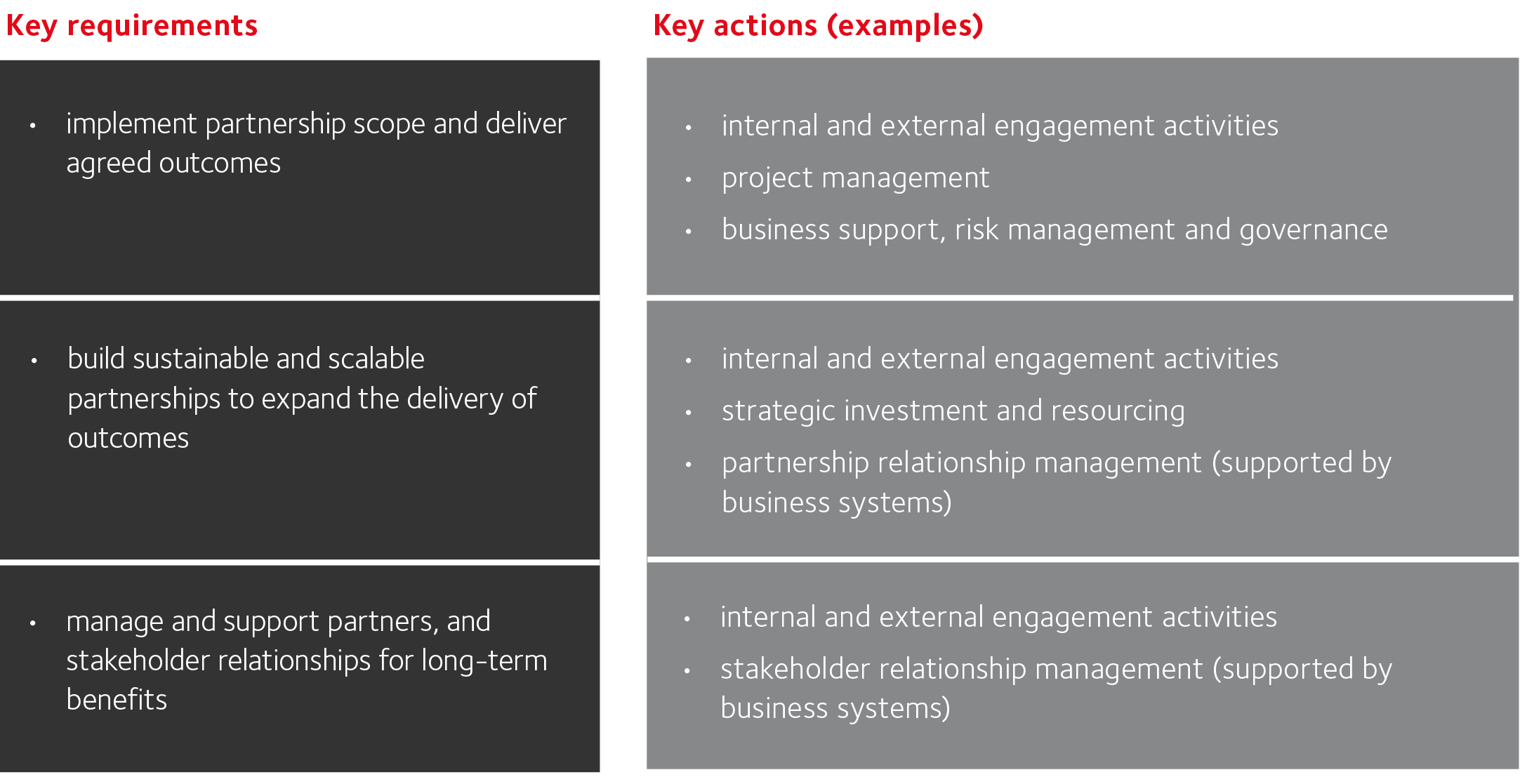

Only through the successful delivery of products or services to the community (and their utilisation by the community) can socio-economic benefits materialise. Deciding which opportunities to pursue, finding the best partners and then structuring mutually beneficial engagements is achieved by the curation of opportunities and the shaping of engagements. But these are only two steps along the road to final delivery.

Once an engagement is established and agreed, universities must also be adept at implementation, especially in the context of aforementioned changing environments. Internal and external environments change over time, introducing challenges and risks, and actual outcomes inevitably vary from expected outcomes. Moreover, because of the nature of exchange between universities and partners, the interests of both parties can diverge. Typically, there are shared returns (or benefits) and risks and these need to be balanced between counter-parties. Accordingly, universities must have expertise in critical elements of delivery including risk mitigation processes, contingency planning and project management. Unless universities deliver on the ‘promise’, reputation, finances and ultimately social dividends can be impaired.

Next, if universities are to truly drive socio-economic benefits along with their partners, they need to establish partnerships which are enduring. This requires universities to think of partnerships beyond the remit of one particular engagement. Enduring partnerships may involve the continual delivery of outcomes. They may involve scaled delivery models (over time) so that products and services can reach the broadest number of end-users in need. They may also involve a broad number of interactions across the full gamut of offerings; e.g. sponsored research, research collaboration, staff exchange, shared infrastructure, scholarships, student placements and so on. Accordingly, universities must have expertise in building sustainable and scalable partnerships and partnership management capabilities to deliver greater benefits.

Finally, enduring partnerships also inevitably involve significant stakeholder management due to the multitude of parties that are involved when dealing with societal challenges. Stakeholders invariably involve those within universities and partners, but also those in the broader community. Universities must be adept at ‘winning votes’ and working in harmony with many stakeholders to deliver long-term socio-economic benefits. Accordingly, universities must have expertise in key stakeholder relationship management to deliver greater benefits.

The following table summarises some key requirements and activities that a university must master to deliver impact.

This ability to ‘deliver’ the products and services which drive long-term positive societal outcomes completes the triumvirate of critical proficiencies for a university.

Interconnectedness of proficiencies

Because the critical proficiencies are linked to the way socio-economic benefits are derived from universities (refer Spheres of Impact), they are interdependent in their connection to one another – all three are required to maximise socio-economic benefits. This link is demonstrated if we consider what happens in the absence of any critical proficiency.

For example, the curation of an offering, and the delivery of the associated solution, in the absence of mutually beneficial partnerships, is unlikely to maximise socio-economic benefits. The offering’s reach and supporting funding are likely to be rationed. The arrangement is unlikely to be sustainable and therefore unlikely to deliver major benefits.

Similarly, the curation of an offering, and the entering into of mutually beneficial partnerships, but not delivering as expected will not maximise socio-economic benefits. In this instance poor performance or unforeseen events are present. This arrangement too is unlikely to be sustainable and unlikely to deliver significant benefits.

Finally, entering into mutually beneficial partnerships that deliver socio-economic benefits, but which are not aligned with the resources or organisational direction of a university, or in its best interests, are not in the province of maximising societal benefits from that university. In this instance there is non-core business being conducted, which is unlikely to be supported in the long term.

Designing organisational character

With an in-depth understanding of the three critical proficiencies, it is possible to design the ‘organisational character’ – the engagement model, operating model and implementation model – required to support the achievement of organisational direction.

The critical proficiencies are the key factors that bind together organisational direction (what we will do) and organisational character (how we will do it) as illustrated and explained below.

Through intent and focus, universities can articulate who they serve, why they are important, how they deliver socio-economic benefits, and what they offer and to whom. This helps determine what universities will do. Then, in that context, determining what activities universities need to master to achieve their organisational directions helps to formulate the ‘organisational character’ required for implementation.

Interestingly and importantly, a change in organisational direction may precipitate a change in organisational character. Similarly, a change in organisational character can influence the achievement of organisational direction. Organisational direction and organisational character are inextricably linked. However, regardless of this interrelatedness and the constant changes to organisational direction or organisational character due to shifting internal and external environments, all universities that deliver impact consistently attain the three critical proficiencies, the glue that binds character with direction. Accordingly, the three critical proficiencies must become bellwethers for universities seeking to derive great impact for our world.

Developing critical proficiencies

Universities that thrive always create highly effective partnerships that are mutually beneficial. Together with partners, they develop meaningful solutions to problems and, in turn, deliver socio-economic benefits our world needs. Therefore, to thrive, universities must attend to the key proficiencies required to derive impact. Continually considering three questions helps this goal:

Question 1: How do we source and organise our offerings to facilitate uptake and utilisation (‘curate’)?

Question 2: How do we source and structure mutually-beneficial and highly-effective engagements (‘shape’)?

Question 3: How do we best work with our partners and stakeholders to bring about outcomes that are beneficial to society (‘deliver’)?

In summary, universities must work out ways to enlist and activate expertise, utilise research capabilities and advance innovations to a stage where they are able to address societal needs in partnership with external parties. They then must be able to shape mutually beneficial engagements and then work together with partners to deliver benefits.

The answers to the above questions must be known across the breadth and depth of universities’ organisational structures in order to thrive and a key activity here involves internal and external engagement which must be carried out in a manner that is consistent with organisational direction. We move next to Purposeful Engagement.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

Introduction image credit: photo by Sergey Zolkin on Unsplash