This is section 3 of a series on the topic of ‘deriving impact from universities’ in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

“A very little key will open a heavy door.”

– Charles Dickens, ‘Hunted Down’, 1859

Section 3. Spheres of Impact

Introduction

Meaningful direction for universities is best established around ‘North Stars’ – those major trends and demographic shifts that impact society. Universities must then couple this with a strong sense of purpose in order to establish ‘intent’ and galvanise shared action within its academic fold. But how is such a strong sense of purpose arrived at? What is the procedure through which that purpose is identified, agreed upon and then garners ‘buy-in’ from all quarters of the university populace?

A convenient answer might be located in the set of worthy social goals ingrained in the visions of most universities around the globe. A convenient answer, but not the correct answer. Such goals are undoubtedly worthy, with their lofty objectives around the production of social, cultural, economic and environmental benefits for our world. But the mere communication or promotion of such goals and objectives does not constitute a university’s purpose.

In order to appreciate the true meaning of purpose in the case of universities, it is necessary to understand how such benefits for society are derived from universities. How exactly are societal benefits obtained from the specific, unique resource that is the university? By first focusing our attention outside the campus walls and on the specific benefits for society that can be derived from universities, we can start to design a conceptual framework that will be central to this series. This framework, known as the ‘Spheres of Impact’, will ultimately facilitate the precise, purposeful type of thinking that is required to hone in on a university’s purpose. Only then can a realistic sense of purpose be imparted across the organisational structure, truly stimulating and releasing potential and yielding new approaches that enhance the ability to derive impact. Therefore, it is to the humble ‘Spheres of Impact’ framework that we now turn our thoughts.

How impact materialises

Ensuring that benefits for society materialise from universities (often described as ‘impact’) can appear at first glance incredibly complex, particularly given the diversity of environments and contexts in which tertiary institutions operate. It can appear complex because it is complex, but making the effort to make sense of this complexity is an important and ultimately far-reaching exercise. To do so, let us first pare back to some basics, leaning on three core yet relatively simple propositions.

Proposition 1

The first proposition is: Benefits from universities materialise through (a) the creation, (b) the provision and (c) the utilisation of education programs and research outcomes.

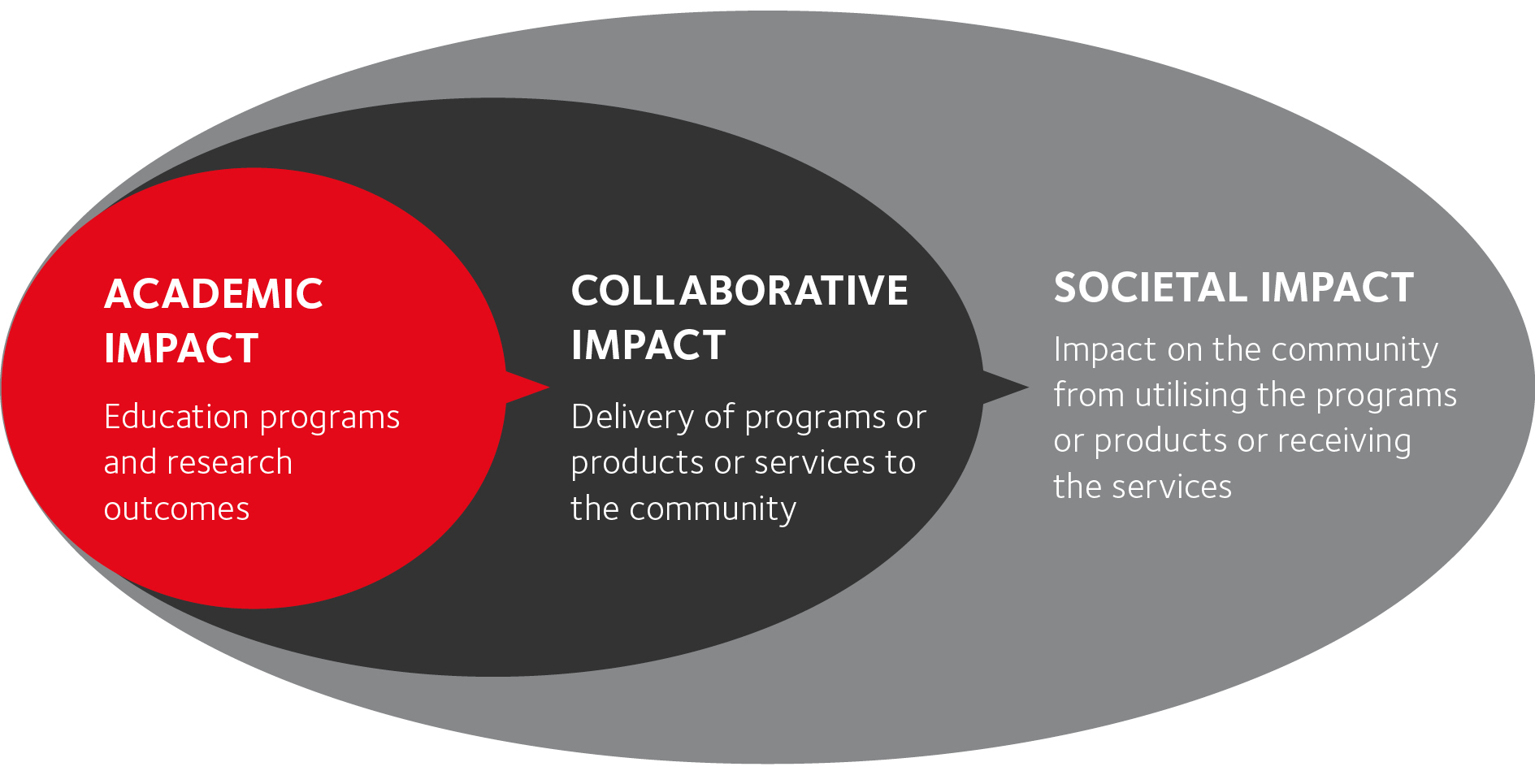

The creation of education programs and research outcomes (including products and services) are the result of ‘Academic Impact’ and when these are provided to the community for use and implementation, universities generate ‘Collaborative Impact’. Through the effective utilisation and implementation of those programs, products and services in the community, ‘Societal Impact’ is derived.

Despite the myriad differences that exist across internal and external environments, impact from universities manifest in these three key ways. From ‘Academic Impact’ to ‘Collaborative Impact’ to ‘Societal Impact’, to be recognised collectively as what we call ‘Spheres of Impact’.

‘Spheres of Impact’

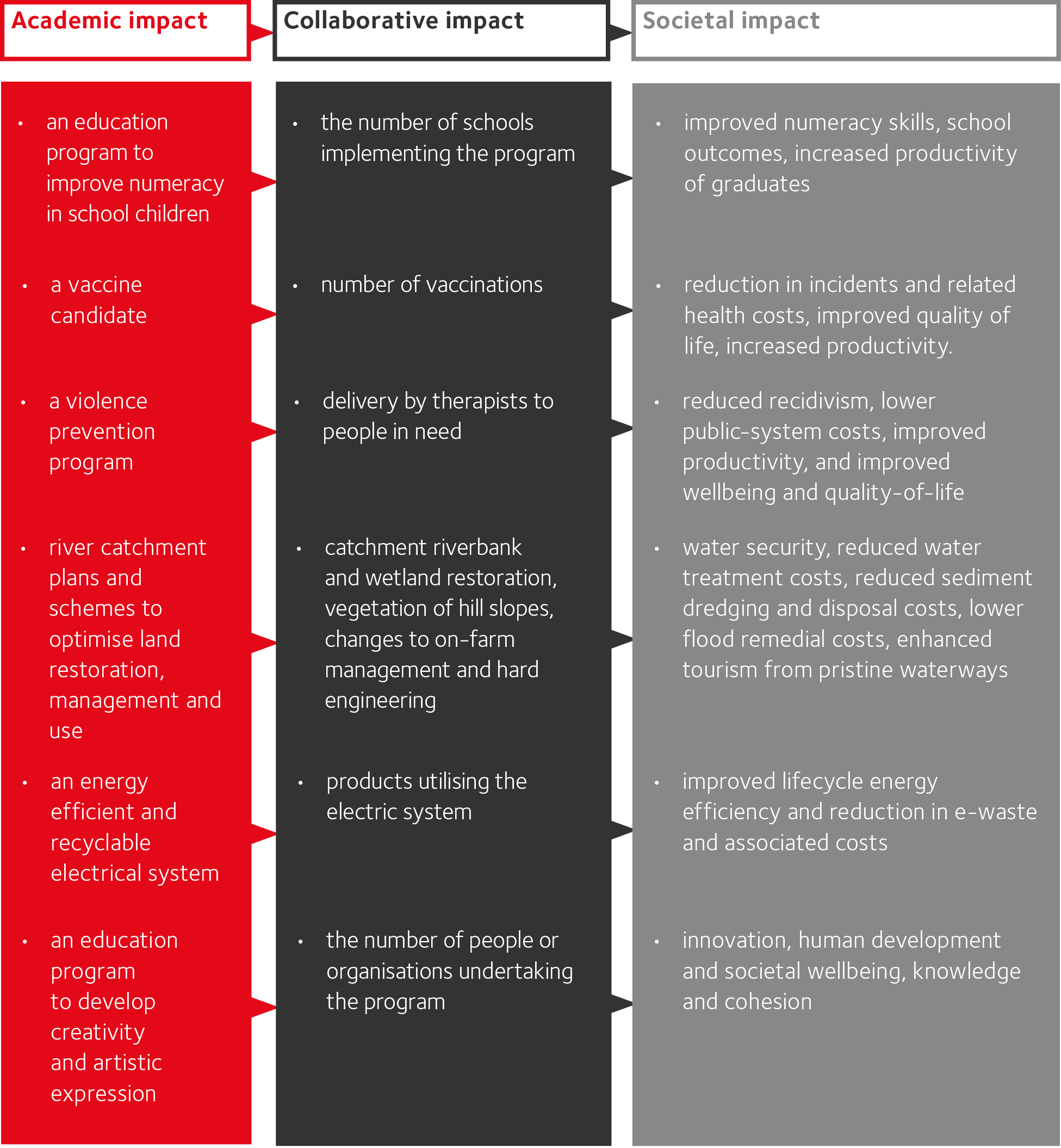

To help demonstrate the ‘Spheres of Impact’ concept and its range, the following table provides some examples from diverse fields – education, life sciences, social sciences, environmental sciences, physical sciences and the arts.

The examples illustrate that regardless of the diversity of underpinning disciplines, impact materialises in a consistent manner.

Proposition 2

The second proposition states: If the potential for great ‘Societal Impact’ is high, so too is the likelihood of ‘Collaborative Impact’ from ‘Academic Impact’.

An example is again useful to explain this proposition, taking the above mentioned vaccine candidate. Typically, a long-term, at-risk, multi-million-dollar investment is required to develop a safe and efficacious vaccine candidate and take it to market. Vaccinations can cost a modest amount per person to deliver, but across a national or even larger population the cost of investment can climb into millions, even billions of dollars. In such a case, and here we pare back to the basics, we must ask what is it that supports such a long-term, at-risk investment and allocation of resources?

Treating the outcomes of a disease may incur costs of tens of thousands of dollars per person. The eradication of that disease or a significant reduction of its effect through vaccinations can save the overall healthcare system a significant multiple of what it costs to develop and provide a vaccine, enabling a healthier and therefore more productive population to contribute so much more to society. The overall societal benefits are profound. It is the potential of such immense ‘Societal Impact’ that justifies the long-term at-risk investment in the development and provision of vaccines. You need look no further than today’s COVID-19 pandemic environment to observe up-close-and-personal just how profound the socio-economic benefits can be from a successful vaccine.

Like the first, the second proposition holds regardless of the diversity of underpinning disciplines (e.g. education, life sciences, social sciences, environmental sciences, physical sciences, the arts). The greater the potential ‘Societal Impact’, the greater the likelihood of ‘Collaborative Impact’ from ‘Academic Impact’.

Proposition 3

The third proposition states: Whilst the delivery of ‘Societal Impact’ can be provided within the confines of universities, partnerships and collaborations with third parties (viz., ‘Collaborative Impact’) are required to truly maximise ‘Societal Impact’.

In other words, a key component of maximising ‘Societal Impact’ involves ensuring that the most people get the most benefit from utilising an education program, product or service. Partners and collaborators are integral to ensuring this occurs.

Extending our vaccine example, without suitable partners outside the university domain to ensure the effective rollout of vaccines around the world, the greatest ‘Societal Impact’ could not materialise. Putting it another way, keeping a vaccine within the confines of a university to deliver (and I concede this is unlikely), strictly rations the overall benefits that can otherwise be derived.

The third proposition, like the previous two, also holds true regardless of the diversity of underpinning disciplines.

Approach to deriving impact

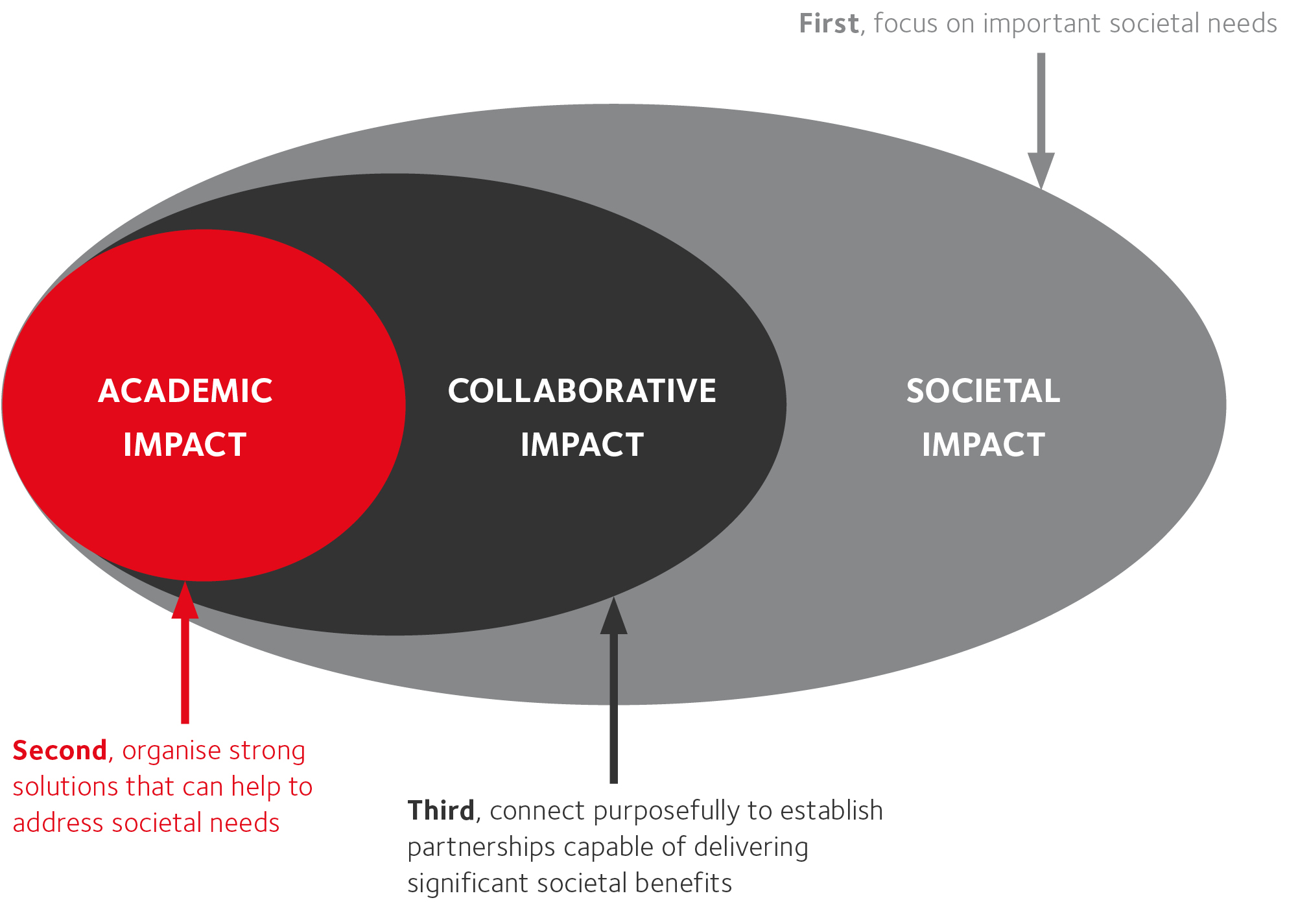

If the three propositions are accepted, universities can galvanise action – irrespective of the discipline – by utilising the following three-pronged axiomatic approach to best direct efforts toward deriving impact.

The first axiom dictates that universities must focus on the nature of significant societal needs. Only then, and this is the second axiom, can universities’ resources be best directed toward developing solutions (e.g. tangible education programs and research outcomes) that address those societal needs. Thirdly, universities must include in their solutions to societal needs those partners and collaborators that can ensure the most people in need obtain the benefits of the solutions. Once the natures of societal needs, university offerings and collaborative partners are determined, universities must then join these dots and purposefully connect each component (or axiom) with another to establish the best arrangements that facilitate the delivery of the greatest ‘Societal Impact’ possible.

Traditionally most universities’ efforts have focused predominantly on maximising ‘Academic Impact’. It is a focus driven by the reality that the best quality education programs and outstanding research outcomes attract quality students and build a reputation attractive to leading educators and researchers. And, without question, this remains a critical component of the value of universities.

Another aspect of delivering impact can be located at some universities where significant investment has been made into identifying the elements of ‘Academic Impact’ that have commercial potential and then translating them through ‘Collaborative Impact’. This so-called ‘technology transfer’ or ‘commercialisation’ has yielded mixed results to date, due perhaps to universities narrowly framing their approach around ‘a solution looking for a problem’ rather than tailored solutions for identified and well-understood societal needs.

Therefore, the challenge for universities is to suitably position education programs and research activities as knowledge-capital in a value chain, with an active intent to maximise the translation of outputs into impact. This requires a shift in perspective on the part of universities away from traditional approaches. The ‘Spheres of Impact’ approach is key to this shift as it helps universities to first investigate, understand and articulate the nature of societal issues, explore the unforeseen and unexpected possibilities alongside intended outcomes, and identify and understand end-users of education programs and research projects much earlier in the process of program and project planning. The ‘Spheres of Impact’ concept opens up the potential to design and redesign approaches that include the best partners and collaborators. It effectively opens the door wide to generating socio-economic impact, which after all is the common objective for all universities.

Articulating ‘purpose’

Understanding the ‘Spheres of Impact’ framework helps universities craft their purpose and with a strong sense of purpose, universities can galvanise shared action. Thus, by continually considering the following three questions, universities can work towards consistently articulating purpose:

Question 1: What is the societal need?

Question 2: How do we create solutions?

Question 3: How do we liberate benefits?

In summary, universities liberate socio-economic benefits by focusing on important societal needs, organising strong offerings to address those needs, and connecting purposefully with partners and collaborators to deliver outcomes.

The successful delivery of quality education programs generates high levels of expertise among graduates or within organisations who can contribute to society. The development of impactful research outcomes provides solutions to needs and wants in society. However, only through the broadest utilisation of education programs and research outcomes by end-users in the community do the most benefits materialise. The value to society can be profound.

Delivering profound socio-economic benefits is ‘the’ university value proposition. It is the reason for public funding and support for universities. To thrive, therefore, universities should seek to continually maximise ‘Societal Impact’ from their ‘Academic Impact’ through ‘Collaborative Impact’. This is a common purpose for universities seeking to maximise impact.

A well understood direction (framed around ‘North Stars’) coupled with purpose (framed around ‘Spheres of Impact’) helps a university establish ‘intent’, an important aspect of setting organisational direction. Therefore, the development of a framework to achieve ‘intent’ now comes into play and will be the focus of the next section – ‘Understanding the Knowledge-Capital Value Chain’.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

Introduction image credit: photo by Linus Nylund on Unsplash