This is Section 11 of the series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

“I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.”

– Jimmy Dean, country music artist (1928-2010)

11. Implementation model – people and teams

Introduction

In the midst of the conceptual blueprint that this series has carefully described, it is crucial that a university not lose sight of an important truth – a university is all about people. The most recent sections of this series, with their focus on how to build organisational character to match organisational direction, have led us towards this crucial human component. Universities aiming to derive impact can nominally position education programs within competitive environments and be seen to pursue research outcomes for society’s betterment. However, any university’s success in such ventures is due in large part to its people, and how they are brought together to collectively solve the problems raised and discussed in earlier sections of this series. An effective implementation model enables this process, granting universities the scope and leeway and quickfire flexibility to assemble teams in the face of opportunity, adversity and uncertainty. Teams of very different people are brought together to deliver innovation, new programs and ground-breaking research projects, drawing from the ‘organising functions’ of a university to get the job done. But how are the teams formed? What are the circumstances that guide or disrupt team selection? How does this fit into the broader, complex university structure? Building on the concepts of core processes and critical proficiencies, this section responds to these questions by introducing and installing a conceptual distinction into the deriving impact framework. It is this key distinction between roles and positions that underpins the potential for refreshed perspectives and effective agility that emerges in this section. To set the scene, we first reconsider the landscape in which today’s university must manage and find its way.

Understanding the operating landscape

Within the maelstrom of internal and external environments, the critical proficiencies and core processes associated with deriving impact do not change. These are the key factors that influence implementation outcomes. Two important propositions, therefore, are relevant to this discussion:

Proposition 1: the ‘constants’

As canvassed in Section 6 of this series, universities must become proficient at (i) curating opportunities, (ii) shaping successful partnerships and (iii) working with other organisations to deliver benefits. These are the matters at which universities must become proficient to derive socio-economic impact. Regardless of differing environments and organisational complexities, these ‘critical proficiencies’ remain constant. This is because socio-economic benefits materialise from universities in a fundamentally common way across all contexts. ‘Core processes’ – the key actions required to deliver socio-economic benefits – must also remain constant. Specifically, these are (i) source offerings, (ii) shape potential offers (and identify potential partners), (iii) decide which partners to work with, (iv) attract those partners, (v) structure enduring partnerships, (vi) work with partners to deliver outcomes and (vii) amplify activities to ensure as many people in need as possible receive the associated benefits. Crucially, these key actions are aligned with the ‘critical proficiencies’.

Proposition 2: the ‘variables’

Operating contexts for universities span three dimensions, namely (i) ‘defined operating context’; (ii) ‘complicated operating context’; and (iii) ‘complex operating context’. As detailed in Section 10 of the series, these contexts dictate different leadership foci and decision-making frameworks depending on how static, active or dynamic the environment. In other words, a leader’s focus regarding the management of people, deployment of resources and ways to make critical decisions must change according to the operating context. This influence of flux also extends to the individual staff members and the composition of teams set up to derive impact. The challenge, here, is to work out how best to harness the collective talents of staff members to drive great socio-economic outcomes, and key to this is the distinction we now draw between ‘positions’ of university staff and ‘roles’ of university staff.

Position and role

The following discussion demonstrates how a clear distinction between position and role can be utilised to ensure that appropriate staff resources are allocated to the actions required in order to derive impact, while also functioning as a means of recognising and rewarding the contributions and input of staff.

‘Position’ is described as the function, responsibility and authority-level of university staff within an existing organisational structure. Academic staff, for example, may hold positions which are senior, mid-career or early-career across an array of academic units such as faculties, schools or research institutes. General staff may hold positions which are senior, middle management or junior within the many ‘organising functions’ of a university such as teaching and learning support, research support, legal services, finance, and facilities management. Executive staff may lead central units or key divisions, groups or faculties within universities. Differing aptitudes and attributes, and varying skills, knowledge and experiences, are associated with the function of each established position.

‘Role’ is a task or job to which an individual may be assigned from time to time, as circumstances arise. A ‘role’ can involve responsibilities and tasks within or across various elements of a university; for example, a role on a steering committee assembled to address a university-wide issue. A ‘role’ may also be temporary and allocated to a specific situation; for example, a role of project leader on a team of staff assembled to undertake a once-off commercial research project. Each ‘role’ requires individuals with different aptitudes and attributes, and various skills, knowledge and experiences.

Universities, therefore, must be prepared to create or activate a role according to the circumstances or opportunities that arise. The attributes, skills and experience required for a given role must be identified, and can be matched with the attributes, skills and experience associated with a certain position. In this way ‘role’ typically requires a certain ‘position’ as a pre-requisite for assignment. Therefore, an individual holding a senior position may be assigned to a role where their expertise and skillset is optimal and required, but where they report to an individual in the role of project leader but whose position in the organisational structure is not necessarily classified as senior.

This example demonstrates an important flexibility that is created by the ‘position/role’ distinction. University staff can be assigned to roles that vary with the changing shape of a university’s opportunity spectrum (see Section 5). Such reassignments have no adverse implications for the positions they hold, either in terms of remuneration or reward. This model also enables a university to handpick people in different positions when forming multi-disciplinary teams to deliver practical and innovative solutions, and ultimately socio-economic benefits.

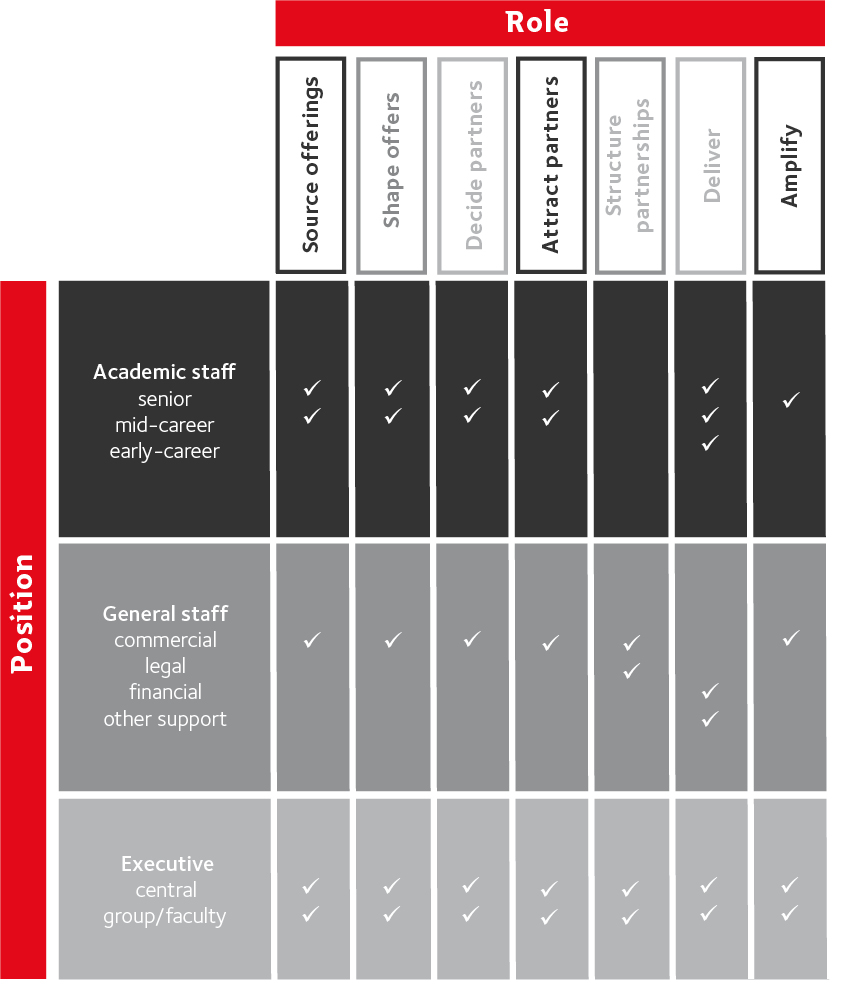

The following diagram (for illustration purposes only) shows various roles based upon the key actions required to deliver socio-economic benefits (viz., ‘core processes’) and the various elements within a university from which individuals in various positions can be drawn. These individuals can play key roles in some or several key actions. This mix and match approach framed around the core processes is integral to assembling the right teams for a given purpose.

Assembling fit-for-purpose teams

The process of selection and allocation must deliver a team fit for purpose, a group of individuals who can function collectively to meet the challenge at hand. The operating context in which this challenge is set must also guide the selection process as each operating context calls for a different set of skills, experience and attributes.

Defined operating contexts involve matters that universities do routinely. For example, many projects within a university are sourced, shaped and undertaken for an external partner by an academic staff member with the requisite expertise. Engagement terms and conditions are typically negotiated together with general staff who have requisite commercial experience. Performance is largely the responsibility of the academic staff member as is managing the ongoing relationship with the external partner, and the development of further projects.

Complicated operating contexts involve multiple options for universities, calling for judicious selection. Here, engagements are typically sourced and undertaken by teams involving academic and general staff members (with requisite expertise), often in partnerships with several third parties. Partnership terms and conditions are negotiated together with staff who have requisite commercial experience. Performance is the responsibility of the academic teams together with partners. Commonly, relationship management involves leading academic staff and also executive staff as a broad suite of university offerings are made available to partners or in partnership.

Complex operating contexts involve universities navigating unpredictable and constantly changing circumstances. A team of staff skilled at generating, testing and assessing opportunities, and rapidly marshalling resources in response to feedback is required. Opportunities are typically undertaken by teams of academic and general staff members (with commercial expertise), often in close consultation with executive and key stakeholders. Performance is the responsibility of the academic and commercial team, with oversight provided by executive. However, because of the dynamism of the environment, a team is responsible for continually navigating the environment with the aim of amplifying outcomes. Therefore, composition of teams is continually changing as required by the dynamic and capricious nature of a complex operating context. This represents a key difference with the defined and complicated operating contexts in the selection and allocation process.

Contribution to success

The ability to distinguish between ‘position’ and ‘role’ means a university can act efficiently and nimbly in seamlessly assigning the right people to the right circumstance at exactly the right moment. It also offers another twofold benefit around the allocation of resources and the attraction and retention of high-calibre staff. The distinction draws into focus the various contributions of staff – both academic and general – across the process of deriving socio-economic benefits, and it effectively calls for roles to be acknowledged and suitably rewarded whether through remuneration and/or promotion to new positions.

The selection of individuals from certain positions for certain roles also reiterates the importance of informing, positioning and prioritising opportunities. In this way, the ‘position/role’ distinction enables universities to prioritise the formation of teams around opportunities and partnerships that are likely to yield the most significant socio-economic impact. These opportunities can range from the many engagements associated with a relatively small proportion of cumulative revenues to a smaller number of large and significant engagements which are associated with the majority of cumulative revenue (and impact). Irrespective of which end of this operational segment spectrum, a mix of attributes and the skills, knowledge and experience of staff is paramount to success, and is enabled by a willingness and ability to adjust and adapt, guided by the distinction between position and role.

Moving towards an implementation model

The architecture of an implementation model capable of deriving impact from universities is inextricably linked to the matters at which universities must become proficient and to an understanding of the contexts in which universities operate. Further, the model is engineered so its four key aspects are synthesised to manage both variance and constancy. The first aspect, honing leadership focus and decision-making frameworks, ultimately prompts related and important questions for a university and the task of bringing its people together to powerful effect at the given time or circumstance.

Question 1: What key actions (i.e. ‘core processes’) are required at this time?

Question 2: What ‘roles’ and associated attributes, skills, knowledge and experience are required?

Question 3: Which individuals from various ‘positions’ must be allocated to those roles?

The response to these questions requires a recognition of operating contexts and their implications for both (a) leadership foci and decision-making frameworks and (b) the nature of people and teams. This is what enables extraordinary people to do extraordinary things. It is also important that the parameters for such extraordinary activity are agreed and delineated and understood. Within these parameters, the values of a university are established, recognised and ultimately flourish as they guide the behaviours of those within their realm. These values – the third part of the implementation model – will be the focus of the next section.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

Introduction image credit: photo by Bobby Burch on Unsplash