This is Section 5 of a series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

“Put first things first and we get second things thrown in; put second things first and we lose both first and second things.”

– C.S.Lewis (1898-1963)

Section 5. Opportunity Spectrum

Introduction

In today’s rapidly changing environments, intensifying competitive landscapes and challenged funding models, universities cannot be everything to everyone – it is an impossibility and needs to be recognised as such. Instead, universities must increasingly make judicious and far-seeing choices about the opportunities and possibilities that present. These business decisions address what consumers and markets to chase, what programs, products or services to offer, what partnerships and collaborations to pursue. These are hard decisions which require a clarity of thought about how a wealth of resources at the proverbial fingertips of a university is to be used.

Any temptation to stretch resources and ‘take on too much’ for the sake of it must be repelled if the end goal of greatest societal impact is to be achieved. There are resources in a university’s gift which cannot meet the societal impact brief as well as alternatives residing elsewhere. In a similar vein, the lure of the limelight must be eschewed if resources are to be utilised for little or no return, apart from a fleeting boost to a tertiary institution’s reputation and little more.

Shrewd decisions, informed by a real and living knowledge of the complexities at play, are required. These are the moments when universities demonstrate they are in tune with their public mandates. Therefore, a key opening question in the effort to gain a true grip on this decision-making process and its ramifications is ‘how do universities ensure the resource decisions they make and the opportunities they pursue are those that deliver the most benefits?’.

A resource allocation challenge

To answer this question, it is first useful to take a hard look at the nature of the decisions that universities – large, complex organisations – must make in relation to allocation of resources. Universities offer a diversity of programs, products and services (e.g. education programs and research outcomes) to an array of consumers just as diverse such as students and organisations such as government and industry–based collaborators. However, like most other organisations, a relatively modest proportion of opportunities taken up by universities in this respect contribute the most significant social, cultural, economic or environmental benefits.

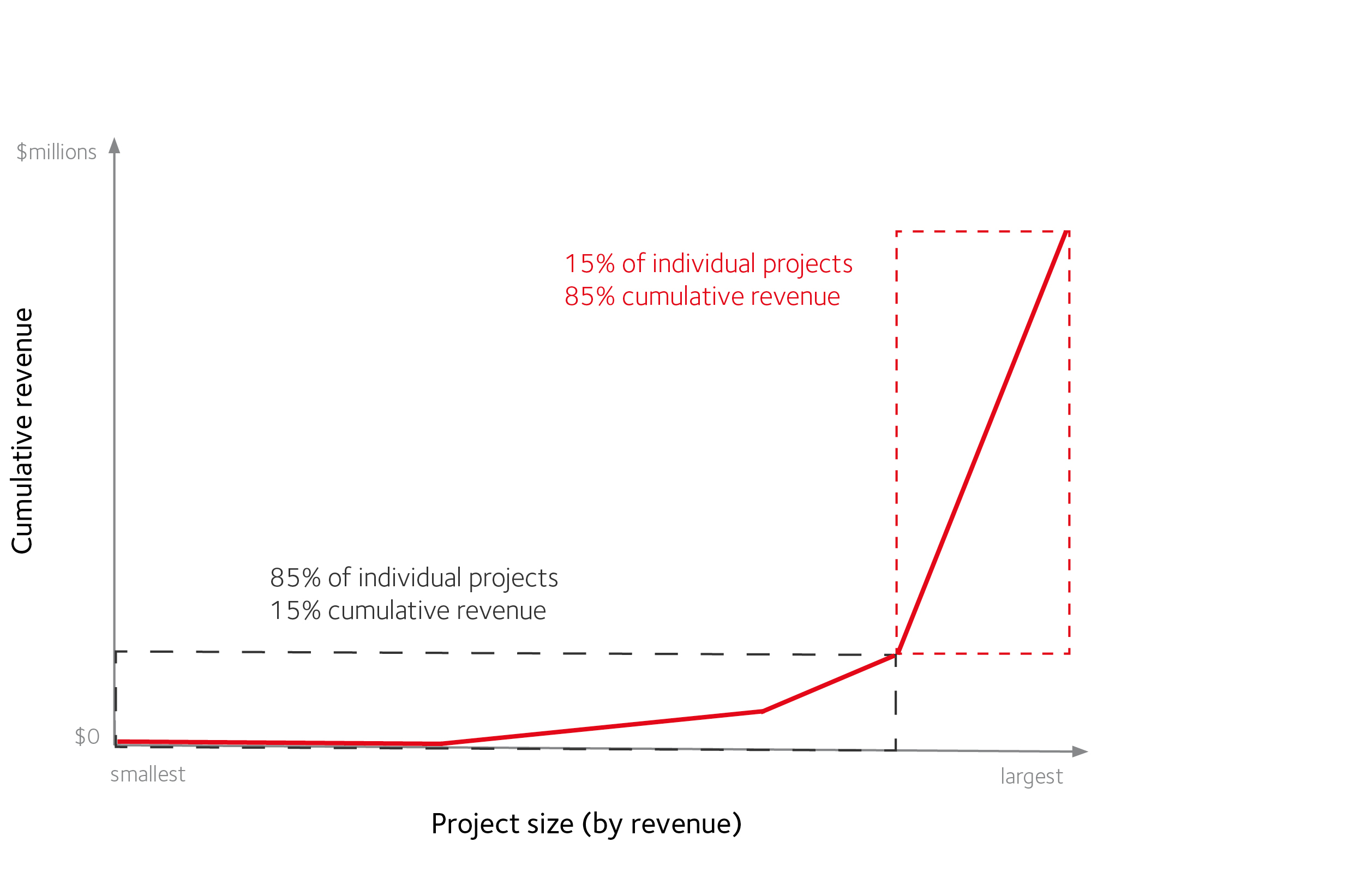

To illustrate this resource allocation challenge, the following diagram uses cumulative revenue[1] (vertical axis) obtained by a university from a suite of engagements ranked from the smallest (left hand side) to largest (right hand side).

This Pareto Principle-like issue is one not unfamiliar to most universities, in this case showing that around 15% of engagements are associated with 85% of cumulative revenue. These proportions can of course vary depending on the natures of activities (e.g. funding associated with various categories of student enrolments versus funding associated with grant applications versus funding associated with commercial partnerships). Despite these variations, the major challenge for universities here is to focus on the opportunities likely to be most impactful when making decisions on allocation of resources – those 15% (say) of opportunities that deliver the majority of impact. In dynamic environments where they are dealing with restricted resource envelopes, this is an imposing test for universities globally.

Meeting the challenge

To maximise impact, universities must be proactive and ensure that resourcing is structured so they can capitalise on opportunities with the promise of significant impact. Such attention to allocation of resources allows other interactions without this significance of impact to be managed in a facilitative and efficient way, but without unduly absorbing available resources. Ultimately, this approach helps universities to discern their ‘opportunity spectrum’, and in turn to optimise resource allocation. It all means being adept at making decisions on (a) how to position competitively, matching consumer needs to competitive strengths (‘positioning’); and (b) which opportunities to pursue, and in what order (‘prioritising’). A closer look at how universities can position and prioritise opportunities follows next.

Positioning

Universities must understand the nature of their resources and how they can be best utilised to deliver impact. This helps to identify a spectrum of opportunities that may be pursued. Universities, therefore, must learn to become proficient at identifying and developing education programs, products and services (‘offerings’) that provide superior value propositions for stakeholders, and in ways that cannot be easily matched by competitors or met by alternatives in a changing environment. Otherwise, a university’s overall efforts are diluted and its outcomes impaired.

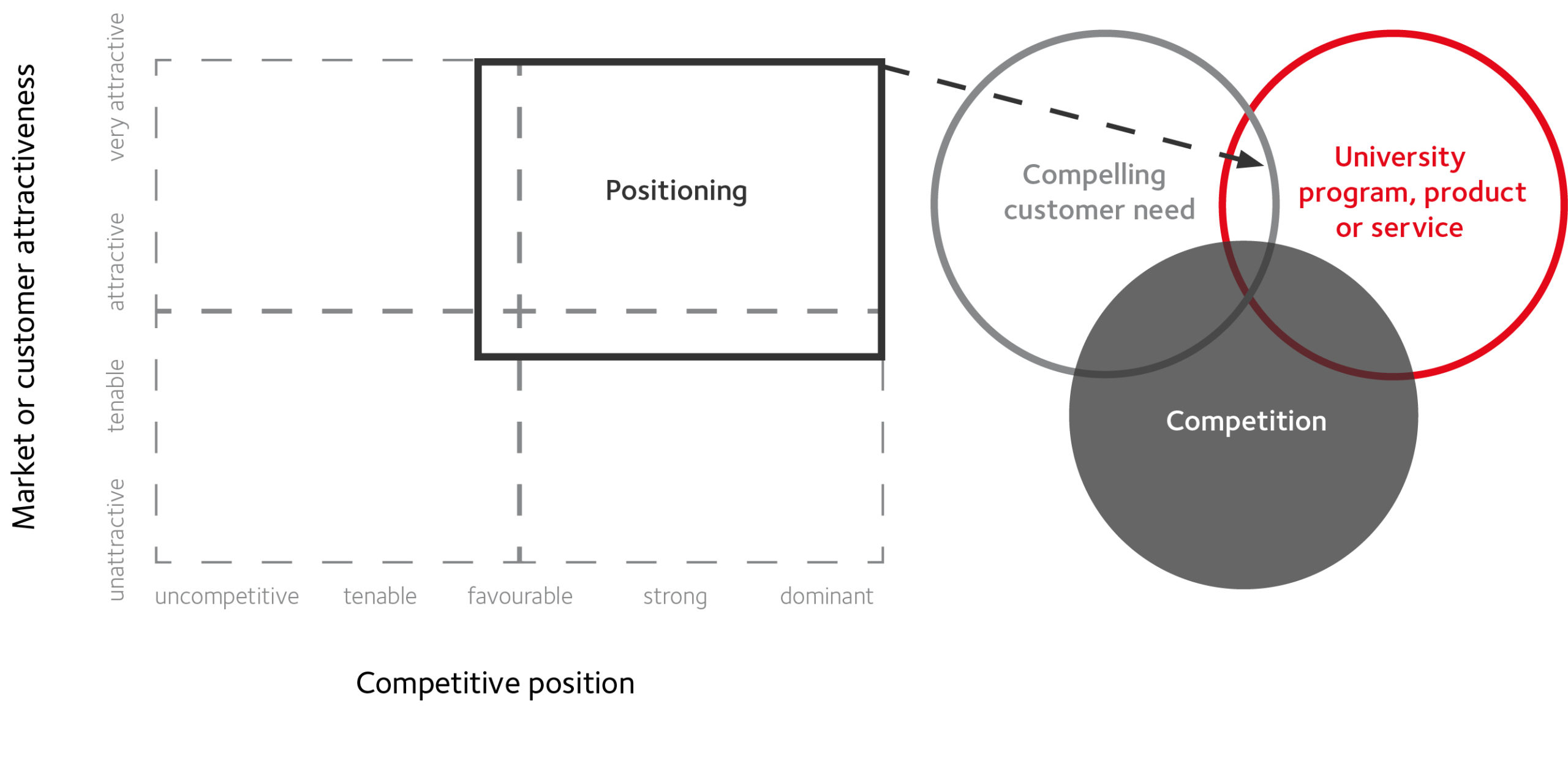

Let’s briefly consider some of the parameters that may be considered in this context, using the illustration below. It is clear that ‘attractive markets’ matched to competitive strengths offer opportunities that are more likely to succeed (as represented in the top right-hand quadrant of the diagram). Large numbers of consumers with compelling needs (e.g. students) or high-growth markets (e.g. healthcare) tend to represent such opportunities. Attractive and very attractive ‘customers’ often involve large organisations that can afford to have a major need addressed.

It is important that universities persist in areas of considerable capability that can address such needs better than competitors and alternatives when required. Solutions to societal needs often involve multi-disciplinary and multi-party approaches with such needs often multi-causal, interconnected and rarely sitting within the remit of a single organisation. Therefore, a focus on the totality of resources (internal and with partners) that can be utilised to address an identified societal need is also important for universities. Then, for example, evidence-based interventions can be coupled with trusted service providers to offer a better solution than those of alternatives or competitors.

To make informed decisions regarding the spectrum of opportunities they may target with confidence, universities need to build appropriate competencies and capabilities.

Prioritising

The decision-making process for universities must also determine which opportunities qualify for advancement. This process of prioritisation requires a university to make choices from the spectrum of opportunities. The application of both outward-looking (‘market’-based) criteria and inward-looking (‘organisation’-based) criteria can help with making the decisions. The following diagram illustrates a process and key decision criteria.

Recalling the ‘spheres of impact’ framework and the ‘knowledge-capital value chain’ detailed in previous sections of this series, universities must first ensure they understand the end-user needs, determine if the market sectors are strategically desirable, and identify realistic paths-to-market including suitable partners and collaborators. If these factors are well understood, opportunities advance to the next stage. Those opportunities for which these factors are not well understood should not be prioritised.

Next, and in addition to market-based criteria, universities must also ensure the requirements of their organisation as a whole are likely to be met. Invariably this involves also determining whether or not a university’s reputation is likely to be enhanced by the opportunities, whether the university can offer a competitive value proposition, and whether or not the likely consideration (e.g. fees, funding, milestone payments, revenues) is sufficient to warrant the allocation of resources. Those opportunities that are likely to enhance reputation, provide a superior value proposition and for which the university will be adequately compensated form priority opportunities.

While there are many different ways to approach prioritising opportunities, the key message is the need to build capabilities and competencies that enable universities to make informed decisions when considering the spectrum of opportunities.

Allocating resources optimally

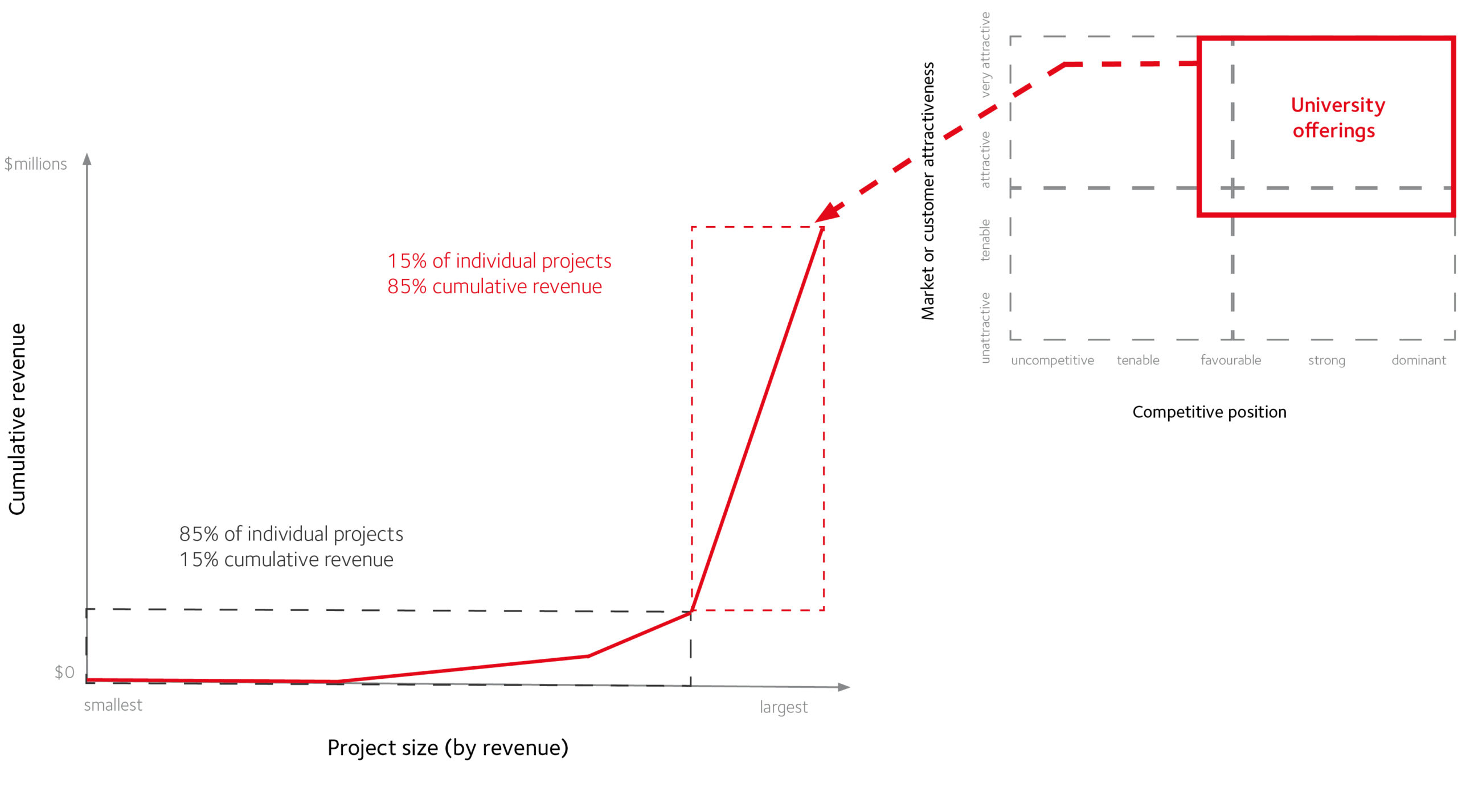

Through the process of positioning and prioritising opportunities, universities can hone organisational direction and invest or allocate available resources optimally. Understanding the different market segments universities can target also helps inform allocation of resources in this context. There are two broad operational segments relevant here, which were indicated earlier through the diagram comparing cumulative revenue with opportunities for impact, which is revisited in the diagram below.

The first segment (indicated by the red dashed box above) comprises large collaborations, and invariably involves the provision of favourable or dominant competitive offerings to attractive markets. Universities need to determine ways to ensure the majority of available resources are allocated to support these engagements.

The first segment (indicated by the red dashed box above) comprises large collaborations, and invariably involves the provision of favourable or dominant competitive offerings to attractive markets. Universities need to determine ways to ensure the majority of available resources are allocated to support these engagements.

The second segment (indicated by the dark grey dashed box above) involves smaller engagements, and like the other, also results in impact. However, judicious allocation of resources toward supporting this segment is required as the impact is likely to sit at the lower end of the scale. It is noteworthy however, that often smaller engagements blossom to larger ones, typically as relationships, track record and experience are built over time.

A third operational segment can exist and involves supporting uncompetitive offerings – those that are unlikely to be successful. Focusing on this segment results in the diversion of available resources away from supporting impactful opportunities. The process of positioning and prioritising opportunities can help mitigate this from occurring.

Discerning an opportunity spectrum

Decisions about competitive positioning and prioritisation must continually be made so the focus of universities is consistently on attractive market segments and leveraging key areas of strength. In a competitive and resource constrained environment, universities can no longer be everything to everyone.

By discerning opportunity spectrums, universities can ensure they pursue those opportunities that are consistent with their directions, purposes and core strategies and likely to derive the most impact from available resource envelopes. This involves recognising markets and opportunities, and exercising good judgment in decisions that involve potential impact. Continually considering the following questions, helps universities in this regard:

Question 1: Is the consumer or organisational need well identified and understood?

Question 2: Is the market segment one that is strategically desirable for the university?

Question 3: Is the university’s offering (alone or in partnership) likely to be superior than competitors or alternatives?

Question 4: Are the university’s reputation and finances likely to be enhanced?

In summary, opportunities for success are represented by a large number of clearly defined end-users with high, addressable needs. Societal needs, receptiveness of end-users, market segments and sizes, key trends, and paths-to-markets must be well known and understood.

In addition, universities should focus resources on those segments in which they are currently active and successful. This allows them to leverage existing opportunities that are of strategic importance where there are identifiable and realistic pathways for the university in each segment or to end-users. Universities must have a clear understanding of the benefits they provide to their consumers (e.g. students, partners or collaborators) and be proficient at offering valuable outcomes; and universities must work with reputable partners in keeping with their overall mission to maximise societal impact. The process of positioning and prioritising enables universities to allocate appropriate resources to those opportunities that have the best chance of delivering impact.

Briefly reflecting on the first five sections of this series, we have explored how awareness of major societal trends (‘North Stars’) and comprehending purpose (‘Spheres of Impact’) help establish a university’s ‘intent’; and then how an understanding of the ‘Knowledge-Capital Value Chain’ and discerned opportunity spectrum (this section) enables a university to ‘focus’. Through intent and focus, universities set organisational direction.

This brings to an end the first part of the series which has presented a way for universities to choose what to do in today’s fast-changing environments. We now shift gears as we move into the second part, and concentrate on ‘getting things done’. This starts with determining the critical proficiencies that must be developed to derive impact from universities.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

[1] I acknowledge that cumulative revenue (e.g. fees, royalties, funding etc) is not a particularly good proxy for funding associated with student enrolments nor overall impact. However, it can be used to illustrate the key resource allocation challenge that universities face.

Introduction image credit: photo by Paul Skorupskas on Unsplash