This is Section 13 of the series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

“To reach a port we must set sail –

Sail, not tie at anchor

Sail, not drift.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt

13. Implementation model – purposeful activities

Introduction

Without suitable stocks of organisational character, a university will fall short in any endeavour to derive impact. An important aspect of organisational character, therefore, involves the considered development of an implementation model which can be a means to a level of coherence and coordination underwritten by a human drive. We have seen in sections 10-12 how this nurtures an ability to sense change and adapt, how it guides the allocation of expertise to the tasks thrown up by turbulent times, and how it forges key values that guide behaviour and actions of staff. And through this process, the vital role of a university’s people has crystalised. Arguably, this is nowhere more pertinent than when decisions around strategy and implementation are at hand. At such moments in time, it is the array of talented, knowledgeable, innovative and experienced people within universities that determines how universities choose what to do (strategy), and how they get that job done (implementation).

An effective implementation model should, therefore, fuse the required organisational direction and organisational character into a cohesive framework whereby the implementers ‘learn as they go’ and adjust accordingly. This notion may be captured in the idea of a sailing boat caught in a storm, manned by a crew with known and defined tasks, yet which continually adjusts to the conditions through coordinated teamwork. These optimised levels of coordinated implementation ultimately guide the boat to its desired destination. At their organisational core are deliberate, informed interactions aimed at getting the job done.

The question of how to best replicate this kind of organised situation in a university is central to this fourth and final section on how an implementation model is developed. In an unpredictable and dynamic world where decisions and actions must occur at a rapid rate, universities need to create a climate in which their people self-motivate while also engaging and communicating with others to help their university derive impact. A multi-step template is devised and presented here in the creation of such a climate. The first of these steps is taken with the assistance of a system-based perspective.

A system-based view of deriving impact

The overarching aim of this thesis is to derive impact from universities for the betterment of society, and to continually realise such a goal, we contend that any organisation – including universities – must undertake five system-based activities. In this situation, the five system-based activities are ‘sensing’, ‘sourcing’, ‘marshalling’, ‘serving’ and finally ‘harmonising’ (which is the most critical of all activities).

In the case of sensing, a university must ensure it is aware of opportunities outside its confines and of community issues that need to be resolved. Therefore, an interactive exercise in sensing what is occurring must continually be undertaken, always with reference to a university’s underlying assets which may be advantageous or fall short of what is required. In the case of sourcing, a university must build or acquire key resources to capture such opportunities, resolve pressing issues, leverage advantages and mitigate shortcomings. This involves the ability to source assets such as talented people, knowledge, research capabilities, innovations, capable partners, and financial capital.

In the case of marshalling, universities with multiple stakeholders must be able to garner the right levels of support and resources and align all key stakeholders toward the delivery of great socio-economic benefits. They must maintain mutually beneficial relationships and satisfy a wide range of stakeholders. In the case of serving, universities must be able to assemble effective teams and productive partnerships that serve the broad social agenda through their interactions in delivering socio-economic benefits.

Finally, in the case of harmonising universities need to make this system of activities function effectively. On a fundamental level, it is clear that sourcing alone cannot achieve its intended impact in isolation from sensing. On a more complex level, the activities around sensing, sourcing, marshalling and serving have to be harmonised to ensure people link insights and ideas, draw together assets and resources, and direct them toward meeting the needs and wants of their stakeholders. This is the process by which context is created for an organisation’s people to pull all activities together and work towards a set of tangible outputs.

From this system-based perspective, the importance of such interactions to a university’s implementation model is evident, as is the need for the organisational structures that foster and nurture these activities. Therefore, this system-based view will now be extrapolated to the implementation model we have advanced in the preceding three sections of the series. It will be demonstrated using the conceptual framework assembled in the previous section on values and behaviour.

Converting purposeful engagement

In the previous section of this series, a framework was created to embed and instil values within and across a university organisation which align with the goal of societal benefit. Importantly, this framework was infused with an acute awareness of the role of people within a university and their abilities to make decisions and act on them.

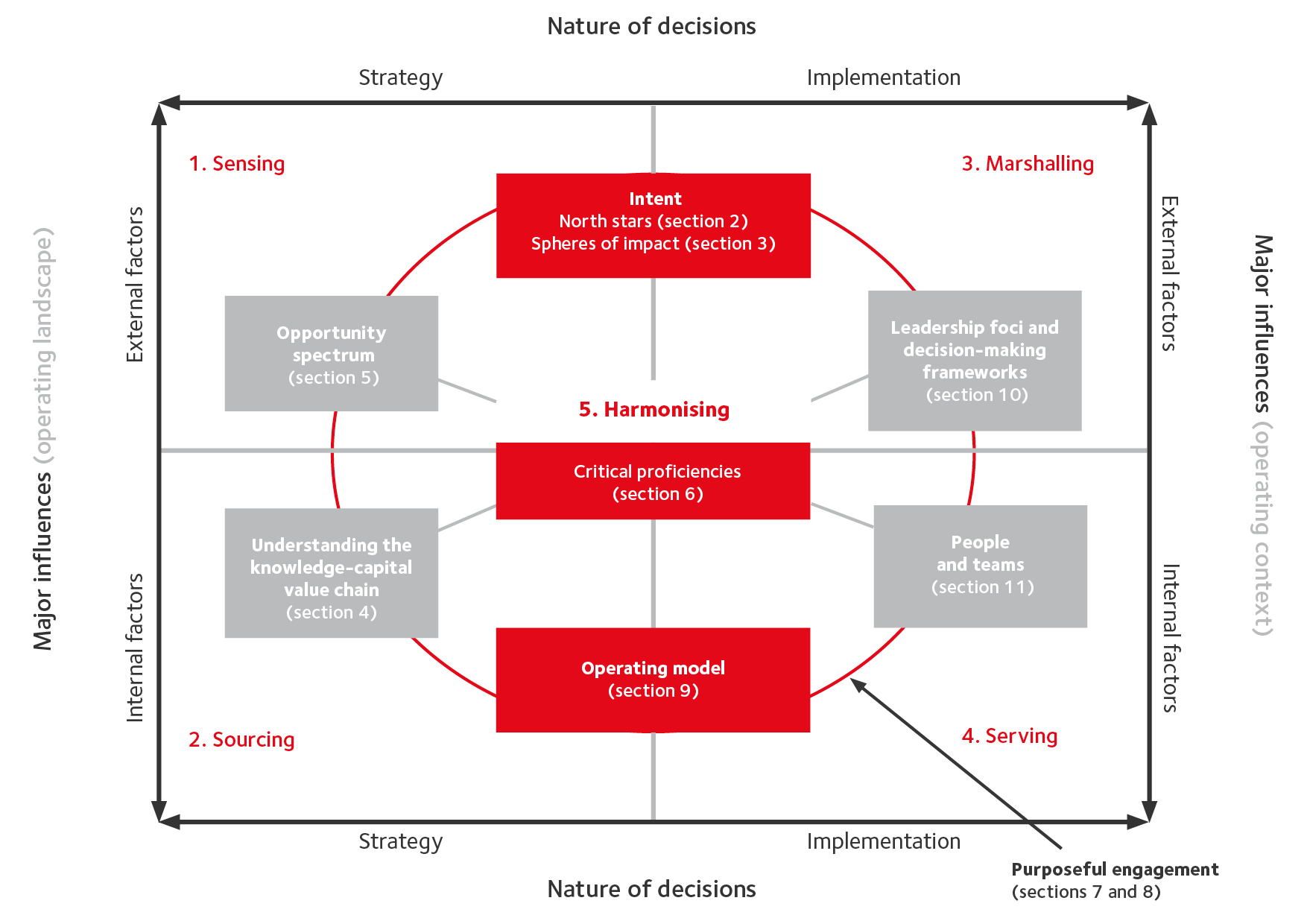

Briefly recapping, the creation of the framework (illustrated below) involved three stages of mapping. In the first stage, the framework considered two dimensions, (a) the natures of required decisions that universities must make (strategy and implementation) and (b) the external and internal environments that influence them. This recognises the inextricable link between strategy and implementation and the external and internal factors that influence them. Second, mapped onto the ensuing matrix were the factors that anchor all decision-making associated with deriving impact (depicted by red boxes in the illustration). Third, also mapped onto the matrix, were the approaches which help frame the information required and associated actions to maximise the derivation of impact (depicted by grey boxes). This conceptual framework ultimately revealed four ‘realms’ around which meaningful values and behaviours can be crafted (see Section 12 of the series).

The framework, in each stage, shows the need to obtain and impart the information necessary for strategic decisions and implementation decisions. Such an endeavour is undertaken through ‘purposeful engagement’, those internal and external engagement activities which operate in tandem, and are aligned with each critical component of deriving impact (see Section 7). Purposeful engagement should be embarked upon with clear, discrete objectives; for example, (a) setting organisational direction, (b) curating opportunities, (c) shaping enduring partnerships and (d) delivering outcomes. Such clarity of objective helps determine the purpose of engaging which in turn frames the questions to be answered and sharpens the ‘focus’ of engagement activities required to answer them.

Approaching engagement purposefully, is an important step away from arbitrary and reactionary activities towards focused system-based activities required to derive impact. Purposeful engagement (to obtain and impart information) and system-based activities (to decide and drive outcomes) are intertwined. Bringing them together, as we propose to do here, requires the right conversations and actions at the right time involving the right people. In the context of an implementation model, these are ‘strategic conversations’, the conduit to determining: (1) what needs to be discussed; (2) who must be informed, addressed or persuaded (internal or external); (3) what each ‘audience’ needs to know; (4) how each audience is best reached; and (5) what is required from each audience. From these strategic conversations emerge tangible activities with: (1) goals (what results are required); (2) priorities (what high-impact issues resources must address); (3) requirements (what specific resources are required for each priority); (4) actions (the key actions that must be taken for each priority); and (5) responsibilities (who takes the actions by when).

In moments of system-based activity, the repertoire of knowledge, expertise, information and skills that has been garnered through purposeful engagement is put to work in the deliberate and intentional interactions of people who want to get the job done. The matrix of system-based activities can therefore be mapped onto the conceptual framework created for our implementation model (see illustration below), enabling a deeper exploration of the interplay at work in an organisational context.

Developing the interplay

The important interplay between purposeful engagement and focused system-based activities is made clear with the fourth layer of mapping onto the conceptual framework. Each of the systems-based activities relevant to an implementation model are now further explored, introducing the idea of purposeful activities to achieve tangible outputs aimed a benefiting society specifically.

Sensing

With ‘sensing’, purposeful engagement involves ‘informing’ decisions, with internal engagement focused on ‘examining’ underlying assets, and external engagement focused on ‘seeking’ societal needs. From here, the purposeful activities of university staff are focused onto (1) direction and purpose (‘North Stars’/ ‘Spheres of Impact’) to establish and impart the university’s ‘intent’; and (2) onto positioning competitively, matching consumer needs to competitive strengths (‘positioning’) where university people decide which opportunities to pursue and in what order (prioritising’) (together, a university’s ‘opportunity spectrum’). And, as with all the identified system-based activities, each purposeful activity must focus on the ‘critical proficiencies’ – the curation of opportunities; shaping of enduring partnerships; and the delivery of socio-economic benefits. In other words: ‘How?’ (can we do it) questions.

Sourcing

With sourcing, purposeful engagement involves (1) ‘enlisting’ opportunities, with internal engagement focused on ‘activating’ potential solutions and external engagement focused on ‘understanding’ needs; and (2) ‘structuring’ partnerships, with internal engagement focused on ‘crafting’ enduring partnerships and external engagement focused on ‘attracting’ the right partners. From here, purposeful activities are then focused onto (1) understanding the knowledge-capital value chain, which includes determining the nature of underlying assets, market segments, delivery mechanisms and types of engagements; (2) operating model, which includes the key actions required to deliver value (‘core processes’), resources that enable the core processes to deliver value (‘enabling systems’) and areas that support operations through internal service provision (‘organisational functions’); and (3) onto the critical proficiencies.

Marshalling

With marshalling, purposeful engagement involves ‘performance’ – internal engagement focused on ‘leading and managing’ to desired outcomes, external engagement focused on ‘amplifying’ the optimal partnerships. From here, purposeful activities are focused onto (1) direction and purpose, to action and impart a university’s ‘intent’; (2) onto the operating context in order to realise the foci of leadership and choose and implement the associated decision-making frameworks; and (3) onto the critical proficiencies.

Serving

With serving, purposeful engagement involves ‘collaboration’ – internal engagement focused on ‘accountability’, external engagement focused on ‘common purpose’. From here, purposeful activities are focused onto (1) the operating model, including required core processes, enabling systems and organisational functions; (2) the people and teams, including the allocation of the right combinations of staff to different core processes required to deliver socio-economic benefits, and (3) the critical proficiencies.

Harmonising

Harmonising, as stated earlier, reflects the abilities of people within an organisation to link insights and ideas, and to draw together assets and resources, and then direct them toward meeting the needs and wants of their stakeholders. It is the specific process by which context is created for an organisation’s people to pull all activities together. Fusing purposeful engagement activities and strategic conversations, harmonising should involve obtaining and imparting the necessary information at the right times and with the right people so that strategic decisions and implementation decisions are effective.

Within the context of an implementation model, harmonising clearly benefits from the embedding of meaningful values that help people make the right choices and that guide behaviours. This embedment is a process of involving people in the choices that have to be made (strategic decisions) and the actions required to convert the choices to outcomes (implementation decisions). And only through the continual hum of purposeful activities can this occur. These are the valuable, ongoing interactions induced by an involved, coordinated and encompassing university climate, where the modes of communication are fluid and their content rich and real.

For universities focused on deriving impact, all purposeful activities should be constantly, creatively, constructively and consistently focused on the critical proficiencies (what we need to be good at) – how to curate opportunities, shape enduring partnerships and deliver great socio-economic benefits.

These are universities with an organisational climate which recognises the uncertainty of operating environments, and how instantly redundant become one-way directives driven by thick, turgid strategic documents. In a dynamic environment, such documents are predicated on a suite of assumptions that may be rendered invalid as soon as they are proofread. They inevitably lose relevance ‘in the trenches’, the maelstrom of day-to-day challenges faced when running an organisation. In our rapidly changing environments, continual informed actions around common purposes are required to drive results. Accepting this premise means staff need to be involved in important issues and have a continual role and input in strategic and implementation decision-making. At the same time, literally, leaders need to spend time in the aforementioned trenches, in the company of clever, well-informed people, constantly engaged in the purposeful activities that forge tangible outcomes, the purposeful activities that guide that sailing boat through treacherous, stormy waters to its intended port.

Conclusion

Organisations work when they maximise the chance that each person, working with others, will grow and contribute to the common good. Leaders fashioned with a traditional command and control approach can no longer motivate people as in yesteryear. Motivation of staff is unlocked from within. You can’t force people to perform, they must want to act and perform. Therefore, leaders must create a climate in which its people will motivate themselves to help a university achieve its ‘intent’. To do this, leaders must alert their people to possibilities, focus them on the right opportunities, and unleash their imagination and spirit to drive outcomes.

Further, leaders must promote the widely dispersed sharing of information, responsibility, and authority, plus total accountability. Leadership foci and decision-making frameworks, people and teams, and values and behaviours (topics previously canvassed in this series) all contribute to this climate. However, only through managing purposeful activities can the right ‘climate’ be established and utilised in ways that bring all aspects together into a cohesive whole capable of deriving impact.

In conclusion, therefore, continually considering three questions helps universities build a climate to support the derivation of impact:

Question 1: What key system-based activities are involved?

Question 2: What purposeful engagement activities are required?

Question 3: What purposeful activities are needed?

This section completes our development of an implementation model to assist a university to derive impact. In a time of environmental complexity, rapid change, heightening competition and hyper-connectedness, competitive advantage depends more and more on building an organisation that is able to act. Armed with the critical components for organisation direction and organisational character, we now shift to the final section which lays out an eco-system approach that can assist a university to derive great socio-economic impact.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

Introduction image credit: photo by Matthew Buchanan on Unsplash