This is Section 14 of the series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

|

“The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” – Aristotle

|

An ecosystem approach to deriving impact

Introduction

Across the 13 preceding parts of this series, we have constructed a framework to calibrate university operations that takes into consideration the resources at their disposal and their bearings in dynamic and competitive environments. Armed with a repertoire of useful concepts, the series has marched forward in the belief that the world has reached a point in time, a much changed and ever-changing point in time, where some form of redux is in order when considering the purpose of the modern university.

The thinking has always been guided by the goal of societal benefit, and how the 21st century goes about deriving the most effective impact from its universities to consistently and repeatedly achieve solutions that benefit society. It is undeniable that the management of university business through these uncertain times and unprecedented environments must be fit for this purpose of societal benefit. On a broader level, it is also clear that a time has arrived for universities to question if they are in fact fit for purpose.

If the response is to be in the affirmative, then the management of a university must be comprehensive. It must also be efficient in the way it maintains and attends to all its constituent parts and components, while keeping a watchful eye on the world outside. This is the lofty yet realistic objective of the framework we have advanced, a university with concepts in harmony, a university which is the epitome of poetry in motion.

In this final part of the series, we describe how an ecosystem approach serves this grand plan, with intricate attention given to priority opportunities, tangible opportunities, active partnerships and deriving impact. First, however, we establish the conceptual terrain in which an ecosystem approach can be founded.

Setting up an Ecosystem Approach

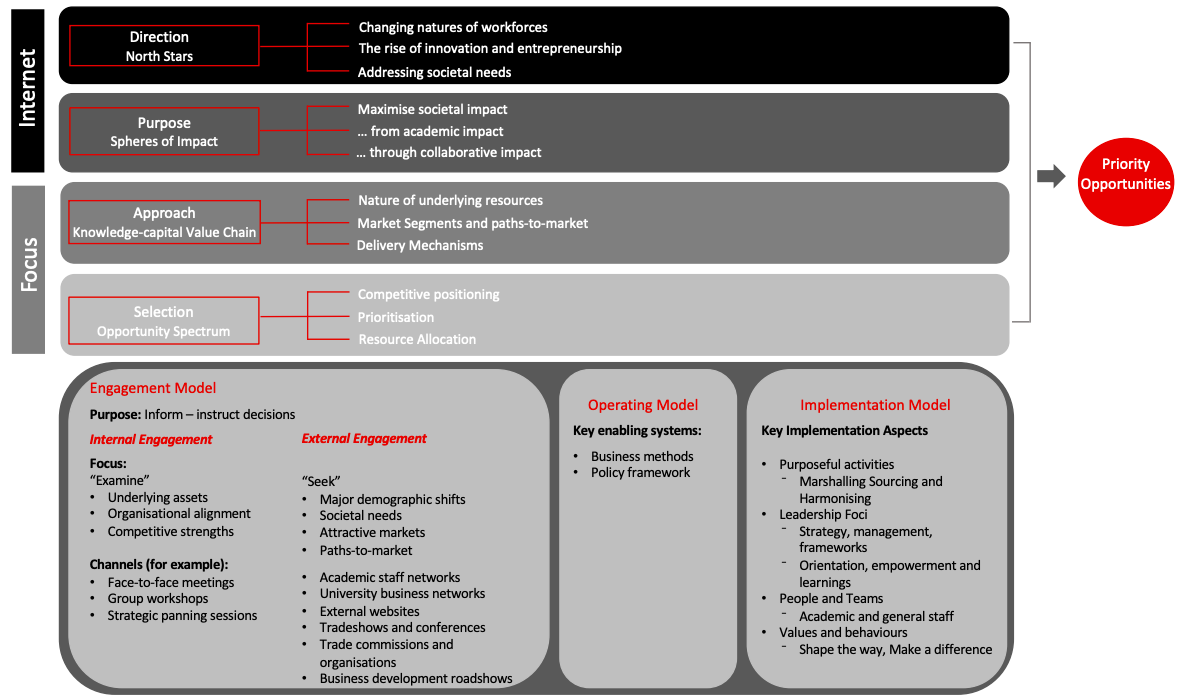

In advancing an ecosystem approach, we briefly revisit a number of concepts at the framework’s core, firstly the unflinching guiding lights that are a university’s ‘north stars’. These are the external constants that guide a university’s activities, and which present as the constantly changing nature of workforces, the unrelenting need to innovate, and the incessant demand for societal benefit.

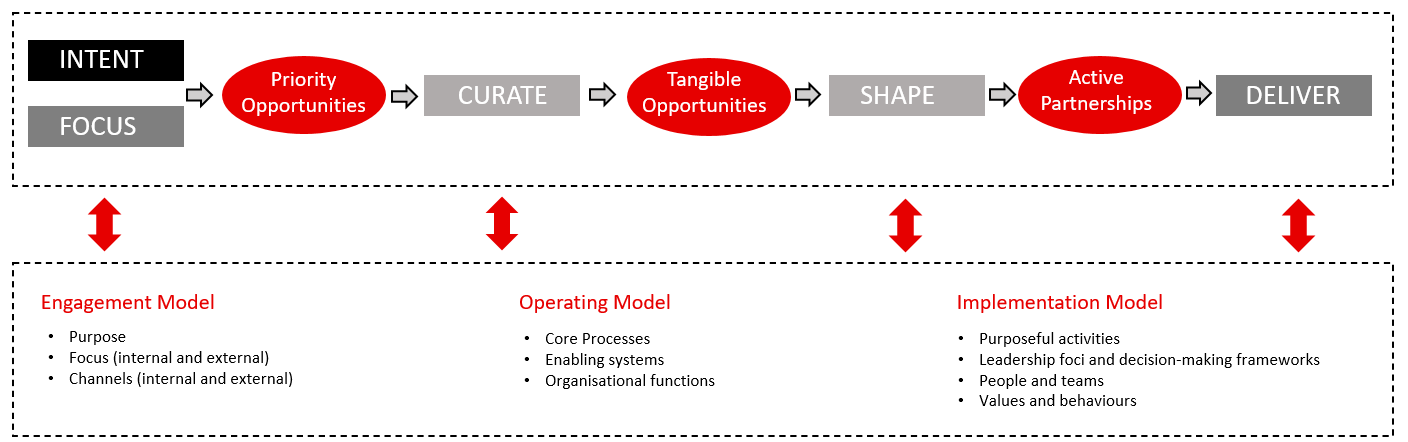

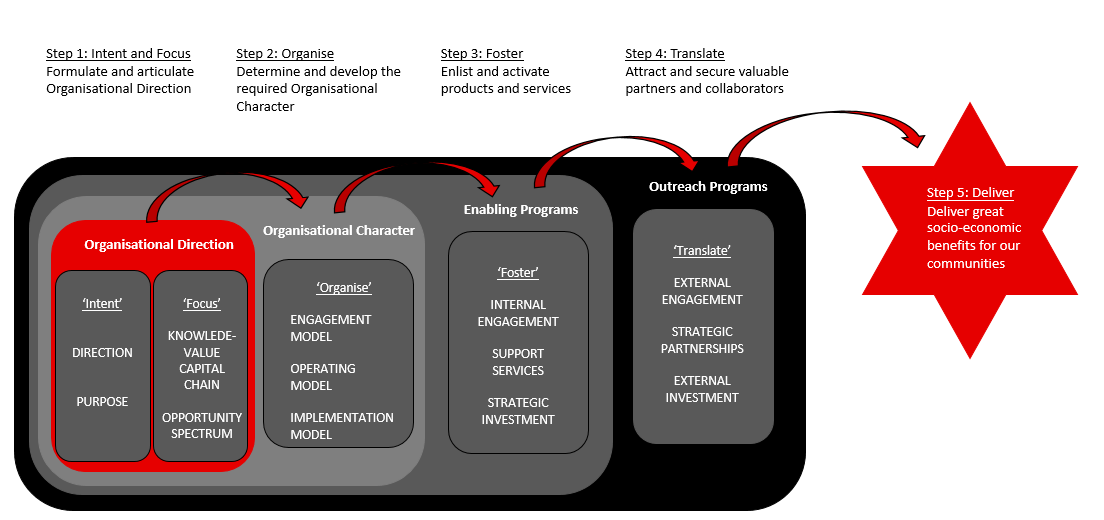

By utilising the deriving impact framework, a university can peer through the white noise of uncertain and dynamic environments, and consistently pare back to basics to establish intent through setting direction and generating purpose. It also enables the university to maintain focus by consistently combining an understanding of the knowledge-capital value chain with discernment of an opportunity spectrum. Intent and focus – ‘deciding what to do’ – are two of those concepts at the framework’s conceptual core. They have a predominantly strategic orientation and put universities into position to take a proactive approach to the identification of what we call priority opportunities.

Three other concepts – curate, shape, deliver – are also revisited here. These relate to ‘how we do it’, those activities in which a university must have expertise (critical proficiencies). These have a predominantly tactical orientation. A university that curates is one that works out ways to enlist and activate expertise, utilise research capabilities and advance innovations. In the act of curating, a university converts priority opportunities to tangible opportunities. A university that shapes is one that generates mutually beneficial engagements with an external partner to address a societal need. In the act of shaping, a university progresses tangible opportunities into active partnerships capable of deriving impact.

In a university, this process of identifying priority opportunities, curating tangible opportunities, shaping active partnerships, and delivering optimum socio-economic impact works in sync with a combination of the engagement, operating and implementation models presented earlier in this series. It is an all-encompassing matrix of inter-related processes whereby a university’s activities, methods, policies, decision-makers and teams coexist and go about their business with a consistency that prevails in an uncertain external environment. This community of interacting university professionals and processes is the lifeblood of an ecosystem approach.

Importantly, it is a relentless process. The successful delivery of a product that benefits society is a goal but never the end goal, as each process regenerates, circling back to intent and focus, again ‘deciding what to do’, but now curating a new suite of opportunities to pursue with the benefit of advanced partnerships and repeated relationships. Over time, complexity, richness and efficiency are incrementally incorporated into the process, drawing on new and different parts of university expertise, and generating the possibility of multiple, customised and targeted societal benefits. In this way, the process not only provides the lifeblood but in actuality builds the ecosystem.

Further development and understanding of an ecosystem approach is made possible through deeper analysis of (i) priority opportunities, (ii) tangible opportunities, (iii) active partnerships, and (iv) deriving impact and related processes.

Priority Opportunities

Discerning a set of priority opportunities requires four key constituents, the first being ‘direction’. Here, a cursory examination of major trends and demographic shifts is informative on (i) the changing nature of workforces, (ii) the sharp rise in entrepreneurship, and (iii) the catalogue of enduring and emerging societal needs towards which a university may aspire and direct activities.

These are the ‘north stars’ which are constant regardless of the dynamism of environments in which any university operates. Universities seeking to derive impact should frame opportunities and establish direction around these (refer Section 2). The second constituent involves the establishment of ‘purpose’. Here, universities galvanise action by focusing on societal needs, organising solutions that address societal needs, and establishing partnerships capable of delivering significant societal benefits (refer Section 3).

Understanding the knowledge-capital value chain, the third constituent, brings to light the attributes of priority opportunities and the various approaches required to advance them. Therefore, a university must have comprehensive knowledge of the nature of underlying assets, the different markets these assets address, the various paths-to-markets and possible delivery mechanisms. This knowledge guides the use of a university’s full suite of assets (knowledge, research capabilities and innovations) and how these may converge in collaboration and partnership with external organisations to deliver the greatest impact possible (refer Section 4).

Finally, universities must discern their opportunity spectrums to ensure they pursue opportunities that are consistent with their directions, purposes, and core strategies, are competitively positioned and prioritised, and are likely to derive the most impact from available resource envelopes (refer Section 5).

The careful, informed judgement of priority opportunities takes place within the all-encompassing matrix of inter-related processes presented above, and it is here that the engagement model takes its place among the pulleys and levers in the engine room of the matrix. In this context, the key purpose of engagement is to ‘inform’ decisions. The focus of internal engagement is on ‘examining’ factors such as underlying assets, organisational alignment, delivery mechanisms and competitive strengths. The focus of external engagement is on ‘seeking’ elements like major demographic shifts, societal needs, attractive markets, and paths to those markets, including potential partners. Various engagement channels that facilitate this purpose are required (refer Section 7 and Section 8). Supporting this are various enabling systems (activities, programs, and methods), particularly business methods and policy framework (refer section 9).

Typically, the operating context is changeable, variable and active, and leadership focuses on strategy, management and frameworks that help garner information, assess it, analyse options and select courses of action (refer section 10). A strategic orientation means executive and senior staff are often involved (refer section 11), with values focused on ‘improving our world’ and ‘shaping the way’ (refer section 12). Associated purposeful activities are aligned predominantly with sensing what is occurring, sourcing key resources and harmonising activities across differing contexts (refer section 13).

Tangible Opportunities

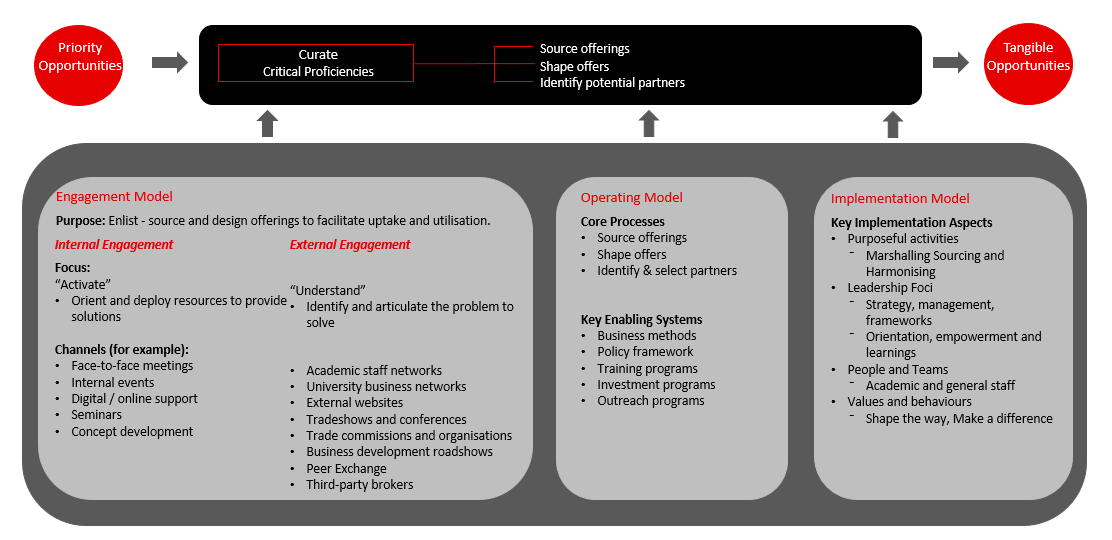

In converting priority opportunities to tangible opportunities, universities near a point where they have assembled the relevant resources and worked through the process of partner identification. It involves different aspects of an engagement model, operating model, and implementation model.

The key purpose of engagement shifts to ‘enlisting’, with external engagement focused on ‘understanding’ the nature of problems and internal engagement focused on ‘activating’ solutions, again utilising various channels for engagement. Core processes – the key actions required – are centred on sourcing offerings, shaping offers, and identifying the best partners, with the help of enabling programs including business methods, policy framework, training programs, investment programs and outreach programs.

The operating context can span from changeable, variable and active on one side, to uncertain, unpredictable and dynamic on the other side. The focus of leadership therefore extends across strategy, management and frameworks, and on to orientation, empowerment, and learnings. This supports the garnering of information and specifying of actions required to advance toward potential partnerships. Here a range of academic and general staff are often involved, with values driven by ‘shaping the way’ and ‘making a difference’. Here purposeful activities predominantly involve sourcing key resources, marshalling multiple stakeholders, and harmonising across various divergent stakeholders.

Active Partnerships

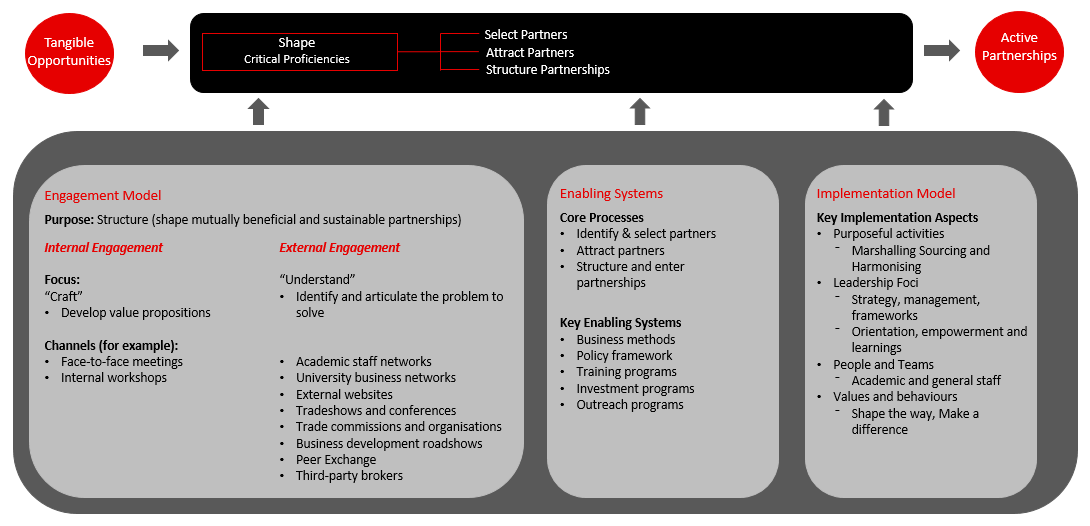

Progressing tangible opportunities to active partnerships again sees different aspects of an engagement model, operating model, and implementation model at play. The key purpose of engagement shifts to ‘structuring’ partnerships, with internal engagement focused on ‘crafting’ value propositions including the right partners and external engagement on ‘understanding’ the problem to solve and on the job of attracting the best partners.

Core processes are all about partner selection, attracting partners and structuring partnerships. Again, in support are a suite of enabling programs including business methods, policy framework, training programs, investment programs and outreach programs. Also again, the operating context is typically changeable, variable, and active, with leadership focused on strategy, management, and frameworks. A range of academic and general staff are involved, with values focused on ‘making a difference’ and ‘shaping the way’. Purposeful activities predominantly involve sourcing key resources, marshalling multiple stakeholders, and harmonising interests.

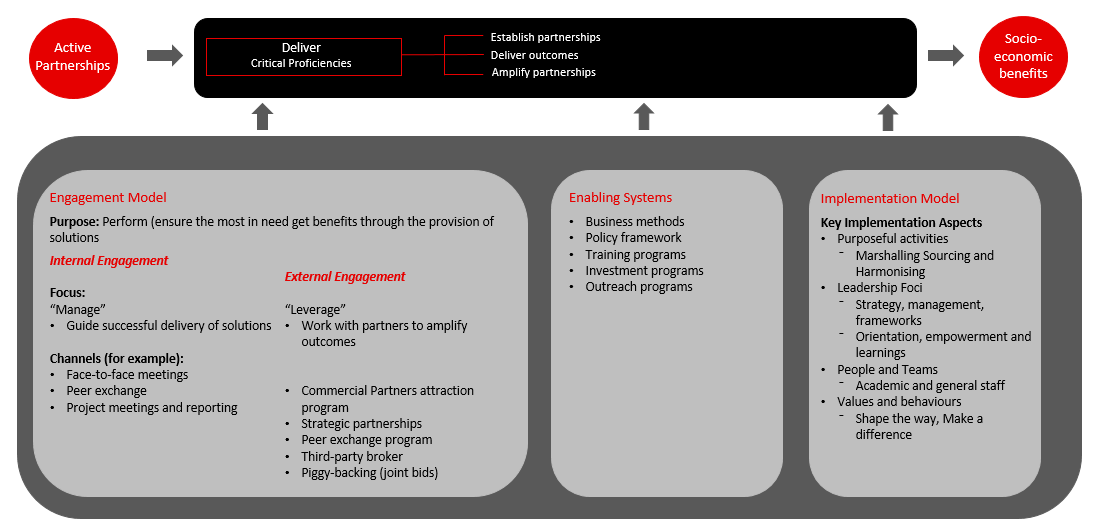

Deriving Impact

To derive impact by converting active partnerships into great socio-economic benefits involves different aspects of the engagement model, operating model, and implementation model. The key purpose of engagement now shifts to ‘performing’ in partnership, with internal engagement focused on ‘managing’ a university’s contributions and external engagement on ‘leveraging’ partners to amplify outcomes. Core processes focus on the agreed partnership, delivery of outcomes and amplification of those outcomes to drive great socio-economic outcomes. In support are a suite of enabling programs including business methods, policy framework, training programs, investment programs and outreach programs.

Here, the operating context typically ranges from certain, predictable, and static to changeable, variable, and active. Leadership foci therefore reaches from objectives and goals, skills and processes to strategy, management, and frameworks. Here a mixture of academic and general staff work together with staff from the partner organisations that are involved. Values are focused on how to ‘improve our world, ‘make a difference’ and being ‘here to help’. Here purposeful activities predominantly involve marshalling multiple stakeholders, serving partners and the community, and harmonising interests.

Towards an Ecosystem Approach

In the above discussion and development of an ecosystem approach, the core concepts of intent, focus, curate, shape and deliver are effectively brought to life at one and the same time. These concepts go to work in an ecosystem where priority opportunities are converted into tangible opportunities, where tangible opportunities are progressed to active partnerships which are advanced and sustained to derive impact that benefits society.

In practical terms, enabling programs such as highly organised internal engagement programs are developed to facilitate outcomes. These may include support services like practitioner-led education and training and investment programs like proof-of-concept funds, seed capital funds and in some instances venture capital funds (either directly, or through alliances). In addition, outreach programs can be nuanced to include refined external engagement programs. These may include strategic partnerships with industry, government and community, and significant external investment.

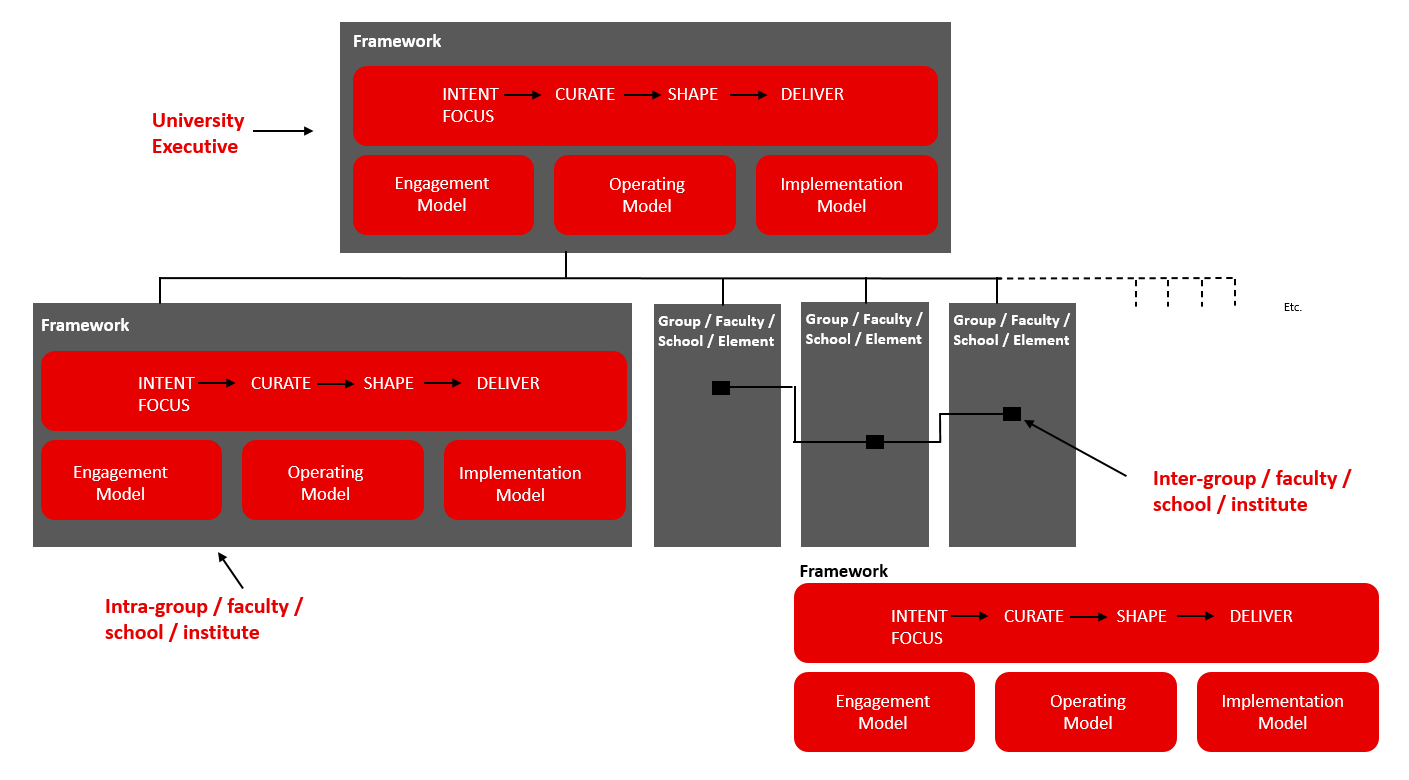

Crucially, the fundamentals of the framework remain the same at all times irrespective of stage of development. The functionality of the framework to derive impact is applied consistently across the depth and span of the organisation regardless of strategic or tactical orientation (as depicted in the graphic below), and through this uniformity in approach and its relentless application, universities generate increasingly sophisticated and targeted approaches over the course of time.

Conclusion

Universities are bubbling with people full of fresh ideas and innovative solutions. These are leaders, academics, researchers, and professionals who see our new century as a time of extraordinary opportunity. They embrace it with all its complexity and uncertainty. They are highly valued by the broad community outside the university domain. Business leaders, entrepreneurs, governments, and students of the world seek out their knowledge and expertise, often with the intention of bettering society.

While the delivery of such socio-economic benefits has forever been a part of the university manifesto, the successful universities of our new century recognise that delivering benefits now hinges on business model design and implementation capability – the need for action. These are the universities that put resources to their best use, get results fast, learn by doing, and make strategy and change simultaneous activities. For these universities, strategy is change, change is strategy. These are the universities that actively shift resources to address market needs, evolving with new trends, demographic shifts, changing funding models and economic conditions. And while they adapt and respond to the world and its uncertain ways, they maintain a consistency to their business practices.

The framework to derive impact presented in this series provides a blueprint for such consistent, unequivocal application of process. It checks the headstrong instinct to pursue one type of engagement, for example start-ups, without prior understanding of a university’s knowledge-capital value chain. It averts a loss of direction when resources are rationed. It prompts consistent internal engagement aimed at preliminary development of products and services that may be future solutions. In this way, the potential societal benefit is nurtured, with enabling programs enlisting, activating and ultimately advancing products and services to a stage where they are capable of delivery to the community. Outreach programs advance the process by identifying and engaging with industry partners without whom expansive delivery does not happen. This involves strategic partnerships, the connection point where collaboration on a service or product turns idea into prototype into product or service utilised by our community. It also involves external investment where the funding to translate products and services to widescale delivery is achieved.

The framework paves the way for meaningful and sustainable connections with business leaders, entrepreneurs, governments, partners, and future leaders in the guise of students. It fosters a dynamic between the university sector and commercial business world and produces and delivers the best ideas to the world in a way that makes a difference.

We conclude with a renewed hope, optimistic that ‘Deriving Impact from Universities’ has delivered on its promise to provide a useful framework for universities to calibrate their operations and futureproof the tremendous social dividend they have historically and hitherto contributed to our world so that it continues well into the future.

Introduction image credit: photo by CaseyHorner on Unsplash