This is Section 10 of the series on the topic of deriving impact from universities in the 21st century, authored by Nicholas Mathiou, Director of Griffith Enterprise.

When clouds appear, wise men put on their cloaks;

When great leaves fall, the winter is at hand;

When the sun sets, who doth not look for night?

– William Shakespeare, Richard III, 2.3

10. Implementation model – leadership and decision-making frameworks

Introduction

Our world has never before been so inundated with extraordinary opportunities and unprecedented challenges. All require solutions, some sooner than others. Providing meaningful and sustainable solutions that benefit society is clearly the remit of a university where deriving impact is paramount. The vision of top universities sees beyond the immediate impact of the solutions they provide, and also spotlights the unique perspectives they bring to different social situations. This is epitomised by their capacity to influence and redefine key sectors of society while addressing the needs and demands of students, partners, entrepreneurs, business leaders, government and the broader community.

However, not every university captures this zeitgeist, and the question must be asked as to why and why not. What is it that sets a university apart when it comes to deriving impact? The answer lies, in part, with how universities position education programs and research outcomes in competitive environments, as explored in sections 1-5 of this series. But there is also a need for universities to carve out their distinct points of difference in order to capture market share. This is difficult when a university is stripped of certainty and cannot envisage what lies ahead with any degree of precision. In the context of increasingly complex and unknown futures, exemplified by a global pandemic, universities must contend with both internal and external environments that are in states of constant and considerable flux. Any effort to fashion a unique selling point is also hindered by the increasingly hyper-connected world in which universities operate, and which makes it easier for one university to effectively clone the programs, products and services of another.

In previous sections on engagement and operating models, this series took two of the three key steps toward organisational character. In this section, we embark on step three in the form of a four-part implementation model which addresses the questions and issues raised above by framing how a university acts as an organisation to deliver great socio-economic benefits.

Dimensions of operating contexts

While the importance of an implementation model cannot be overstated, there are two vital points that should be highlighted from the outset. Firstly, an implementation model is critical to a university’s ability to sense change and adapt to it, clearly crucial when operating within dynamic environments. To this end, a process of continual learning is required to equip and empower university staff to think and act effectively and constantly develop university capabilities in anticipation of and preparation for a future that is less and less predictable.

Secondly, an implementation model is difficult to clone unlike many of the individual programs, products and services a university may offer. It is here that a university can source immense competitive advantage but only by first identifying and acknowledging the range of operating contexts it faces. These are the contexts that ultimately define the focus of leadership and determine associated decision-making frameworks, the first of four key aspects of an implementation model. The full ensemble incorporates: (1) leadership foci and associated decision-making frameworks; (2) people and teams; (3) values and behaviours; and (4) purposeful activities.

In combination, these fours aspects provide most of the drive and coherence required to achieve organisational character and successfully derive impact from universities. The latter three will be explored in the following sections of this series. We must first establish the varying operating contexts that universities face, and the defining effect these have on the focus of university leadership and decision-making process (and indeed, the other three aspects).

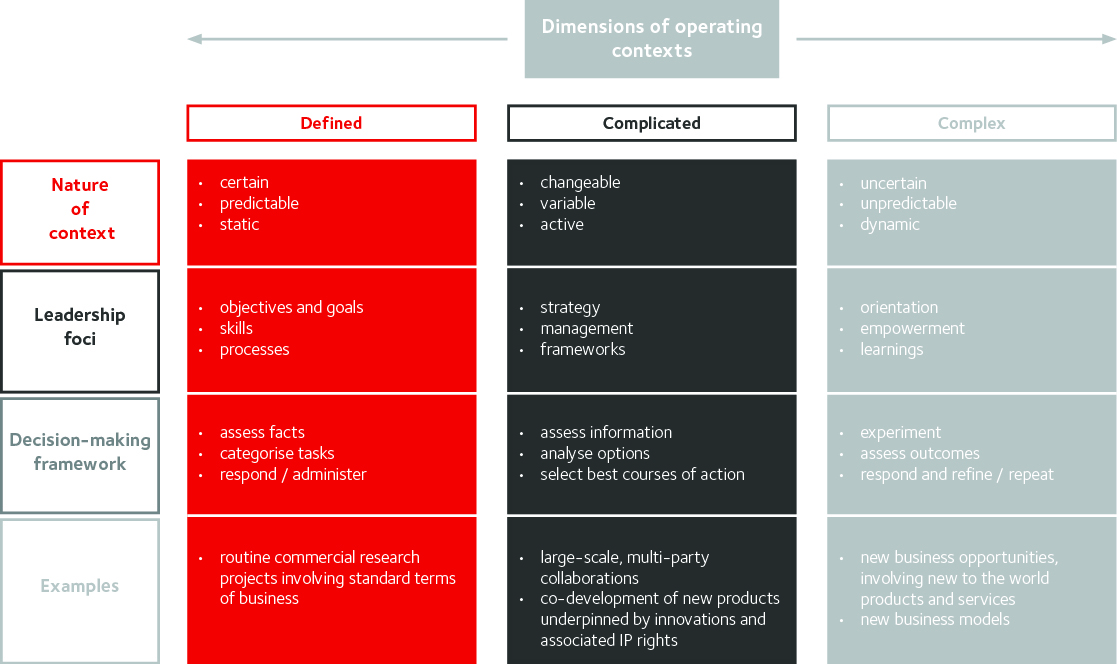

The environments within which universities operate can be quite different and the nature of the associated operating contexts span various dimensions. These start with (a) certain, predictable, static environments – ‘defined operating context’, moving on to (b) changeable, variable, active environments – ‘complicated operating context’; and extending through to (c) uncertain, unpredictable, dynamic environments – ‘complex operating context’.

Universities have a diversity of functions and operate across an array of environments; therefore, leadership focus and decision-making cannot be a one-size-fits-all proposition. Approaches to leadership and decision-making must change depending on the operating context as it is perceived. This is one of the most important concepts to understand, and will next be explored in detail as it applies to each of the aforementioned dimensions. We begin with the ‘defined operating context’.

Defined operating context

Leadership within universities is multifaceted but mainly focuses on organisational direction, people and operations. Within certain, predictable and static environments, leadership typically focuses on (1) establishing clear objectives and goals to drive organisational direction; (2) ensuring staff are appropriately skilled and experienced; and (3) establishing appropriate policies, protocols and processes to support operations. Until recently, most universities have been able to operate in this way.

In a defined operating context, universities can operate in a routine fashion. Most matters are discernible and processes exist to manage them. The enrolment of students, the scheduling of lectures, the lodging of grant applications (traditional to universities) involve highly defined (and refined) processes. The decision-making frameworks typically involve assessing the facts, classifying them, and then responding accordingly. Perhaps because of the relatively certain and predictable nature of this operating context, many of the associated processes are currently being automated, enabled by many of the ‘digital’ platforms that now exist.

The administration of small-scale consulting or commercial research projects on standard terms of business provides an example of an approach to deriving impact that tends to fall into a defined operating context. Here, staff need to be adept at identifying common factors, reviewing contractual arrangements and responding appropriately. Managers and staff have access to necessary information for dealing with the situations, and therefore directives tend to be straightforward, decisions easily delegated, and many functions automated.

In defined operating contexts you often see emphasis on benchmarking against best practice and a major focus on ‘key performance indicators’. Many readers who operate in defined operating contexts will be quite familiar with these managerial approaches.

Complicated operating context

Our changing world is becoming increasingly uncertain and less predictable. Universities are of necessity establishing new leadership approaches and decision-making frameworks, which we now touch upon.

As environmental uncertainty increases, more potential options and ensuing actions arise, and the focus of leadership must shift to (1) setting organisational direction and strategy (e.g. how universities position and obtain sustainable competitive advantage); (2) organisation and management of people to facilitate implementation of strategy; and, (3) frameworks that support operations (e.g. conceptual structures, information and principles). Most universities have shifted significant emphasis toward this context since the turn of the millennium, particularly as traditional funding models are changing and competition is intensifying.

In a complicated operating context, there typically are matters that involve multiple options for universities, where judicious selection is required. In this operating context, the decision-making frameworks involve assessing information, analysing options, and responding accordingly.

Articulating societal needs and root-causes of challenges, shaping and assessing potential solutions, and selecting the best avenues and partners to maximise outcomes is an example of an approach to deriving impact that falls into a complicated operating context. Here, there is a relationship between cause and effect, but numerous staff with various expertise, skills and experience are required to make choices. Leaders must navigate expert opinions, whilst stimulating ideas and innovative solutions. Information is not always exhaustive or readily available, and judicious decisions need time.

There is much in the literature, particularly in the fields of strategy, management, marketing and general business regarding how to navigate complicated operating contexts, and it is beyond the scope of this section of the series to address them all. One key aspect – the way people and teams are selected, assembled and operate – is critical in this operating context, and elaborated on in the next section of this series.

Complex operating context

A complex operating context involves navigating unpredictable, and constantly changing circumstances. Much of contemporary business now faces aspects of this, particularly with new business establishment (e.g. entrepreneurship) or business disruption (due to rapidly emerging alternatives or competition). New business opportunities or dynamic business environments require non-traditional planning cycles and approaches. ‘Right’ answers don’t exist. Rather, information must be continually discovered and acted upon.

Universities are not exempt from this operating context, and those seeking to derive impact can also face inherently unpredictable or dynamic environments. This is often experienced with entrepreneurial endeavours, which is becoming more of a priority for universities (see section 2 of this series, North Stars)[1] and with changes to the ways knowledge, innovations and research capabilities are obtained by end-users (including students, organisations and the community).

Uncertain and rapidly changing environments render many traditional leadership approaches ineffective. In these circumstances, leadership shifts focus to providing clear direction through well articulated purpose, and shaping the context in which people can make up their own minds, apply their creativity and make effective decisions. People must be empowered to do extraordinary things, but efforts must be aligned. Here, leadership must also focus on values that guide behaviour (explored later in this series) and on establishing a learning environment, where effective communication, feedback and empowerment of staff, within the overarching purpose, are mission critical.

Decision-making frameworks, in this context typically involve experimenting (in ways that yield useful knowledge and where it is relatively safe to fail[2]), and based on information from that experimentation, assessing and responding accordingly. Here, continually obtaining knowledge to inform decisions and next steps is critical. Leaders must allow a path forward to be revealed and be flexible as new information is obtained. Setting boundaries, rather than making directives and allowing opportunities to evolve through continual actions is required. Open communication is essential to create a ‘learning environment’. A key to success in complex operating contexts is the creation of an ‘environment’ from which successful outcomes can emerge.

Directing leadership focus and decision-making frameworks

Through an understanding of the contexts in which they operate, universities can guide leadership focus for organisational direction, people and operations, along with the application of associated decision-making frameworks when seeking to derive socio-economic impact.

Continually considering the following three questions helps universities to hone leadership focus and decision-making frameworks toward establishing their overarching implementation model:

Question 1: What is the nature of our operating context? (defined, complicated or complex?)

Question 2: What should the focus of leadership be?

Question 3: What decision-making framework should we utilise?

An understanding of how operating context dictates the appropriate leadership foci and decision-making frameworks is the first step toward the introduction of an implementation model. In the next section of the series, we turn to the second of the four aspects of an implementation model: people and teams.

Read the previous article from this series.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nicholas Mathiou is Director of Griffith Enterprise, the innovation and enterprise office of Griffith University. He has extensive commercial experience, having established and grown innovation-based businesses and organisations. He is driven by an ambition to see great social dividends emerge through university-based innovation. He has a deep understanding of the unique challenges involved in advancing innovations within complex organisations and in dynamic environments.

[1] Complex environments are also experienced with so called ‘black swan’ events – for example a pandemic – which are less frequently experienced, but which precipitate very fluid environments.

[2] Success in complex operating contexts is about ‘learning fast’ not ‘failing fast’. The later expression in my view is unhelpful, as it connotes an undevised or opportunistic rather than considered approach to experimentation and ‘testing the market’.

Introduction image credit: photo by Jean Wimmerlin on Unsplash