Speech by Rowan Callick at the China Studies Centre, Melbourne University, March 14 2019

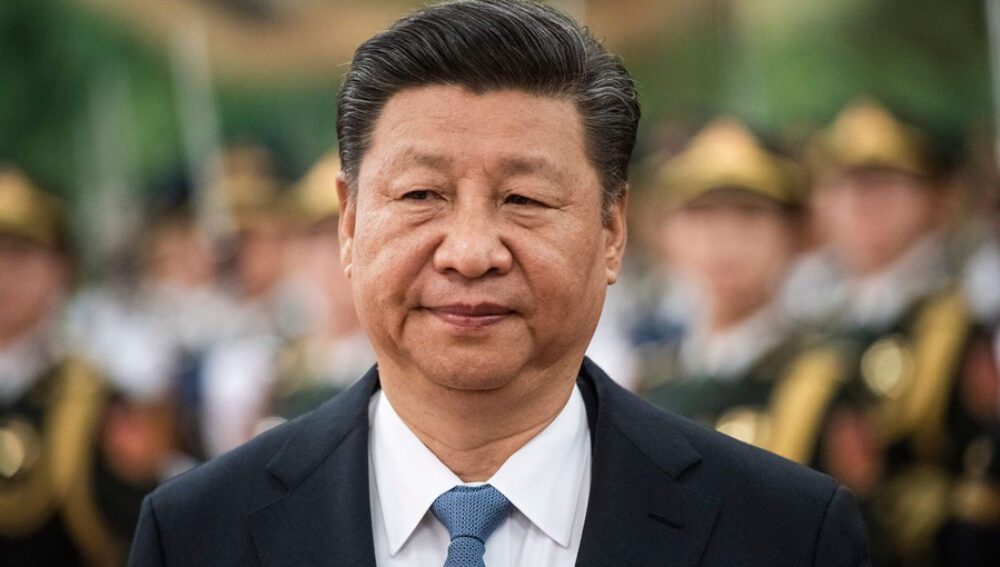

Xi Jinping has become the most powerful person in the world.

Chiang Kai-shek was not, in his time. Mao Zedong was not. Nor were Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao.

But Xi’s greater authority over his own communist party, and over his nation – reinforced by the unprecedented control and surveillance provided by vast and unknowable state spending – is augmented by his freshly minted global role. He has assumed the position of the default lender, sometimes donor, to the developing world, the hero of the Davos global conglomerate elite, the redefiner of how the UN views human rights to accentuate his desired “community of common destiny” rather than universal values, crucially he is weaponizing China’s economic ascendance to achieve myriad party-state goals.

In this talk I’m going to raise some key questions, even though some will have to remain unanswered – but pursued I hope by some of you here this evening. I shall then touch on a bit of the relevant history, and on the way the system works in China, before focusing on Xi himself, his story then how he is using his power, then finally a little on the party before asking briefly what this phenomenon might mean for the future.

I am defining power, as many dictionaries do, as in this context “the capacity to direct or influence the behaviour of others or the course of events.” The meaning of power also incorporates the extent of “authority that is delegated to a person or institution.”

Donald Trump has a more powerful military; but he and his Republicans don’t own it. Xi’s military is an arm of the communist party over which he has assumed unchallenged power, and he has replaced virtually the entire leadership of the People’s Liberation Army in the last half dozen years, removing with impunity top generals on corruption or other charges

Trump, despite ensuring a conservative majority in the Supreme Court, is fighting to stay beyond the grip of lawyers seeking to bring him to book; Xi’s party has reinforced its full suzerainty over the legal system. Trump has to contend with a rebellious legislature, trimming his executive wish-list including building his wall; Xi received, a year ago almost to the day, 2,958 votes at the National People’s Congress to end term limits on his presidency, with two votes against and three abstentions. He has few if any legislative constraints. Trump is constantly battling America’s media and entertainment establishment, and what he calls “fake news”; Xi faced no push-back when he said Chinese journalists’ “family name is Party.” All mainstream media in China are accountable to Xi via his Propaganda Department delegates, while he personally chairs the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission that forms policy and directs implementation of the Chinese internet in the name of cyber sovereignty

Xi’s power derives of course from his election by the General Committee of the party as General Secretary on November 15, 2012 – the same day he also became chairman of the Central Military Commission.

But how did this happen? What were the threads that he followed to ensure his selection above Li Keqiang, who had appeared to be favoured by predecessor Hu Jintao? Who, or which faction or influence, played the decisive role in ensuring Xi’s selection? And since then, in what ways has he strengthened mightily the power associated with the role of General Secretary?

As such questions indicate, we do have a sense of what we don’t know; the impact of China’s power is palpable, to put it mildly. We are in the territory of what Donald Rumsfeld described as “known unknowns.”

There are, then, no ready definitive answers. Much remains hidden in China, secret even from the knowledge of other members of that Central Committee. In some respects, how China is ruled today – how decisions are made, and who by – is more mysterious than at any time during the 20th century, or indeed during the Qing dynasty whose protocols and rituals were so rigorously applied. Xi has in effect replaced, as China’s senior policy-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee – which he reduced from nine men to seven (no woman has ever been a member) – with the leading small groups or commissions that he has reinvigorated and developed, and of which he personally chairs at least six – those for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, for Foreign Affairs and National Security, for Taiwan Affairs, for Financial and Economic Work, for Network Security and Information Technology, and for Deepening Reforms of National Defence and the Military. The CSIS lists 83 such groups, getting on for half of them established under Xi. Their membership, associated bureaucracies, meeting details and programs and resolutions, remain virtually unknown – even though from time to time China Central TV may even broadcast tantalising snatches of their meetings.. Such mystery accords the puller of the strings even more power. It is difficult to conceive of a policy being brought from one of Xi’s leading small groups to the PSC for formal approval, and being rejected or significantly amended. And Xi’s closest political ally, Wang Qishan, is not even a member of the Politburo any more. He is Vice President, a formal role on the government rather than party side of the ledger. But Xi a year ago asked the NPC to abolish term limits for the vice president as well as for the president, so that Wang can serve alongside him as suits.

It was Wang who surprised many by being appointed head of the central commission for disciplinary inspection in 2012, when he had been expected to become China’s top economic leader. Had Wang lost his way? Had Xi lost confidence in him? Of course, most were looking at the announcement the wrong way round. They should have asked: what does it mean for the CCDI, for anti-corruption efforts, for party discipline? It meant that these had now become Xi’s top priority, and he had given responsibility for this purification, this drive for loyalty, to his most trusted aide. Wang’s present role sees him focus on international affairs, again indicating a shift in Xi’s own priorities.

Xi’s authority appears to derive from a combination of: the absolute sovereignty of his communist party over all things China; his “red genes” flowing from his vice-premier father Xi Zhongxun to create a family heritage which cannot be challenged; his “rejuvenating” leadership – principally in purging and purifying the party, and centralising and personalising power; and the disarray of those nations and leaders representing the chief rival to Xi Thought – the liberal democratic worldview.

Can such power be limited, staunched or even reversed, within China or without? This is a giant question for our times, and requires burrowing back a bit to try to discern more about its true source, or sources.

Thus some at least of the questions. Now, the history.

China’s dynasties carried their own momentum when they were succeeding, but of course when circumstances – sometimes external and beyond imperial control – took a turn for the worse, the “mandate of heaven” was deemed to have slipped away, and however desperately the dynasty sought to keep it within its hands, it kept seeping away like water. Unlike power changes in many other parts of the world, where a clean break was perceived as crucial by the new rulers, in China legitimacy has been underlined by claiming continuity. China has been ruled for roughly half the last 750 years by foreign invaders, first the Mongolians as the Yuan dynasty, then the Manchus as the Qing dynasty. In each case, the emperors swiftly adopted many cultural elements that made them appear thoroughly Chinese. But usually, with a fresh twist; while being Chinese, the Yuan emperors remained Mongolian, and the Qing emperors Manchu, including in language and in religious worldviews. This desire for continuity can be seen clearly in the wonderful exhibition from Taipei’s National Palace Museum now at the Art Gallery of NSW, demonstrating how emperors maintained and even appointed curators to enhance the treasures they inherited from previous dynasties.

Xi – not of course needing to establish a new dynasty, but nevertheless needing to appeal to precedent and to regime continuity – presided at the end of last year over a series of events marking the 40th anniversary of the reform-and-opening era inaugurated by Deng Xiaoping at the third plenum of the 11th Central Committee. But he naturally added his own fresh twist. For instance, after a painting of Xi himself, the second largest painting in an exhibition at Beijing’s National Art Museum to celebrate the reform era, by artist Liu Yuyi, showed father Xi Zhongxun lecturing China’s leaders of 40 years ago including Deng, seated nearest, smoking a ubiquitous Panda brand cigarette.

The source of the power to rule China – the mandate – has inevitably been contested from time to time. The same struggle has occurred in virtually every other country or jurisdiction in the world. The Dismissal year here in Australia. The periods of the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution in Britain. The long period between the rise of the military-industrial complex in Japan and then the end of the Pacific war and the start of American occupation, when dynastic rule teetered on the brink, and after which power migrated clearly into the hands of LDP prime ministers. Similar uncertainties have from time to time seized places from Indonesia to India to Russia. Papua New Guinea had two claimant governments in 2011, ultimately resolved in favour of whoever could gain a majority in the legislature. And we’re seeing confusion about the source of power play out in Venezuela right now, in an agonising way.

The period from the end of the Manchu imperial dynasty in 1912 was characterised by uncertainty about the source of power in China, an uncertainty that has been used for millennia, through to Xi’s own rule, as a reason for decisive, undisputable central control, and against tugs towards federalism or democracy.

The Xinhai Revolution of 1911 was triggered by the mutiny of Qing soldiers in Wuchang, Hubei, who were inspired by Sun Yat-sen, who then returned from exile. But Yuan Shikai, a northern army general belatedly appointed prime minister, interposed himself between this popular uprising and the emperor. In negotiations with the Dowager Empress Longyu, he forcibly persuaded the dynastic family to require the six year old Emperor Pu Yi to abdicate. The resulting statement said: “The whole country is tending towards a republican form of government. It is the Will of Heaven, and it is certain that we could not reject the people’s desire for the sake of one family’s honour and glory. We, the Emperor, hand over the sovereignty to the people. We decide the form of government to be a constitutional republic.” In this last declaration, the emperor appointed Yuan Shikai to organise a provisional government for what it described as “the union of the five peoples: Manchus, Han Chinese, Mongolians, Mohammedans and Tibetans.”

Sun Yat-sen had three months earlier been elected provisional president of China at a meeting of provincial representatives. But as the receiver of the formal abdication, Yuan seized control. A National Assembly that was elected in 1913 by a more widespread franchise in 1913 failed in its attempts to grapple control over Yuan, who a couple of years later convened his own “representative assembly”, that invited him to take the throne from January 1 1916, as Emperor Hongxian. But that was the peak of his power, the watershed. After that over-reach, most of his supporters abandoned him and protests erupted around China. He was never accepted as an emperor, and his power ebbed. This illustrates the potentially elusive – and for would-be rulers frustrating – nature of the locus of real power.

In contrast, we saw how during a party conference during the Long March lasting just three days in January 1935, Mao Zedong seized the hour to gain effective power, which he never then relinquished substantially until his death 41 years later. There, at Zunyi in Guizhou, he wrestled control from the Soviet Union’s advisor Otto Braun and from general secretary Bo Gu, over the military strategy of the party.

With the advent of the People’s Republic in 1949, authority was placed with the Central Committee of the Communist Party, which for two decades or so reliably conceded that all significant power was in the hands of Mao Zedong, who had become the first chairman of the committee in 1945. The Cultural Revolution was in part triggered, however, by Mao’s fears that his power, his control of the party and thus of China was waning. After he died in 1976, Hua Guofeng and Hu Yaobang were both appointed party chairman, but real power had shifted from their hands well before the post was abolished in 1982 – in effect into the hands of Deng Xiaoping, who was never the titular head of the party.

Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao were identified as leaders by Deng. But wherein lies the core of Xi Jinping’s extraordinary power, sufficient to abolish term limits on the presidency? Investigating its true locus may also help consider whether even Xi might encounter constraints to his seemingly boundless ambitions. I need to add in parenthesis, that China’s presidency is not of course of itself a core element of Xi’s power; Mao and Deng for instance were never presidents. However, Xi wished to mark his new age as clearly distinct from Deng’s. His Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, now incorporated into both party and state constitutions, stresses that. It was Deng who introduced the constraints on leaders, including requiring retirement at set ages, in order to prevent a return to the madness of the final Mao years that threatened the whole future of the party. And in this new era, China’s leaders are required to travel widely to display the country’s rejuvenation, in turn requiring the maximum protocol only guaranteed to state presidents.

Now, the system.

Formally, the system works in a predictable manner, suffused with ritual. The National Party Congress (there have been 19 so far, the last 16 months ago) is held every five years – and delegates are chosen in theory by the 89 million ordinary members in party branches through a process of steps ascending a pyramid structure of ever larger branches where ultimate acceptability will be determined by senior cadres. In 2012 Xi became the first general secretary to be born under the People’s Republic. The national congress where he was chosen, comprised 2,270 delegates, plus an additional 57 “specially invited delegates” – principally former party heavyweights, who also have votes. These 2,327 delegates elected the Central Committee, of 205 members and 168 alternates who attended when the prime members were unable to do so. They then chose the 25 members of the Politburo, as well as the Politburo Standing Committee (the PSC) – in this case and still today, seven members. In theory, the PSC reports to the Politburo which reports to the Central Committee, but in practice the PSC holds authority over both parent bodies. The general secretary is chosen by the Central Committee. A convention was understood to have set in, after Mao, that general secretaries each serve two five-year terms – although this only actually happened for Hu; Jiang held office a little longer, and retained irritatingly for Hu the chairmanship of the Central Military Commission for a couple of extra years.

The executive government, which in theory is responsible to the legislature – the National People’s Congress that meets annually around this time for a fortnight, and operates through a standing committee between congresses – in practice is the implementing agency of the party. It is the party that determines policy. Almost every Chinese institution from government ministries to private companies, contain party committees that direct policy within those institutions and appoint the top managers, or at least have the capacity to do so when required. Article 1 of the Chinese national constitution says “the People’s Republic is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship,” and that “the socialist system is the basic system of the PRC.” A new sentence was added a year ago that makes explicit that “the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the Communist Party of China.”

This national constitution thus operates as a mere subset of the party’s own constitution. China’s constitution – which includes the right to vote, freedom of speech and assembly and of religious belief and from unlawful search, and other liberal values, is simply not appealable in China’s courts. It carries almost no practical value for those whom it describes as citizens.

The system is elevated far above any requirement to be seen to please its subjects. Its purity, hard-won through Xi’s purges via the CCDI, is almost an end in itself. Thus we look in vain for elements of popular accessibility in Xi’s style or demeanour. His power derives in no way from the oratory or wit that, say, finally played such a large part in landing Winston Churchill centre stage. Rebecca MacKinnon, then a professor at Hong Kong University, explained to me a few years back: “Chinese leaders give boring speeches because they can. Giving interesting speeches – by Western standards – has little upside and much potential downside. People might quote them out of context or misinterpret them, or the leader might mis-speak in an effort at extemporaneous rhetorical flourish, with consequences that might be used against him in internal political power struggles. In Chinese culture, if you’re already powerful you don’t want to act as if there is a need to win anybody over. If you act as if you care what people think of your speeches, you’re admitting weakness.” It also, she says, runs counter to Chinese culture for a powerful person even to admit to being powerful, or talking about it. “It’s what you do, not what you say that counts.”

Now Xi, that man of power, himself.

Xi Jinping has in the last couple of years considerably extended the role of the party, so that it has taken over full responsibility for a range of functions – such as supervision of religions and of the media – formerly theoretically controlled by the state.

He appears to have little time for his own government, which he tends to view as comprising essentially hired hands. He is determined to make meaningless that famous phrase applied to the pragmatism of Chinese provincial life: “the emperor is far off and the mountains are far away.” Xi stands on a metaphorical high hill, and his gaze reaches directly to all party cadres, who take their lead from him, in determining the future of the party-state. Of course, he requires the emergence of competent and zealous provincial party secretaries – which he has now mostly secured – and beyond them especially, county level party chiefs with similar qualities, in order to ensure his decisions are implemented. But this is a project indeed in hand. The mountains are being laid low.

A dozen years ago, at the 17th party congress in October 2007, Xi’s career stood in the balance. He had been suddenly elevated from Zhejiang to party secretary of Shanghai, succeeding a disgraced predecessor. He then vaulted at the 17th congress straight from the Central Committee to the Politburo Standing Committee. And crucially, he was there ranked first among those whose ages made them eligible to succeed Hu Jintao in the top job at the following congress.

The ritual of the emergence of the new PSC team – unchanged during the four times I’ve observed it first-hand – involves a longish wait with media, diplomats and others in one of the larger halls of the Great Hall of the People. We await the final act of the congress, the vote of the Central Committee, meeting elsewhere in the building, for the top party roles. Then there’s a hush and the MC announces that the new PSC team is about to join us. They walk out, beauty-parade style, usually in blue suits and dark ties, in strict order of party status.

It was only then, in 2007, that it became clear that Xi was favoured by the party elite to succeed Hu.

Today’s premier Li Keqiang, a couple of years younger, whose own educational attainments are considerably greater, and who had also accomplished much in his provincial roles, stepped into the room behind Xi. I confess to having written for The Australian then that it appeared “China’s ruling party is persisting with a collegiate leadership style that depends less on a single charismatic figure than it did under Mao and Deng.”

Recent years have proven how wrong I was.

The imperial Forbidden City was known as The Deep Within; a name also well applied to the communist party’s simulacrum, its own leadership compound just to the west, Zhongnanhai, where Xi at first grew up. He lost his high schooling to the Cultural Revolution when the family was banished to Yan’an near Xi’an, then studied chemical engineering at Qinghua University in Beijing, as a “worker-peasant-soldier student,” going on later to gain a doctorate of law there, focused on Marxist theory and ideological education. Xi’s father Xi Zhongxun was a Long March veteran and economic reformer, who became a vice premier and also vice chairman of the National People’s Congress. Xi is thus a “princeling,” one of the taizidang who follow in their fathers’ party footsteps.

Hu had been cautious about endorsing too many princelings, given his focus on broadening the wealth base and reducing party privilege. But Xi Xhongxun remained loyal to the reformist party chief Hu Yaobang even after Hu was removed from power. And Hu Jintao was also a supporter of his namesake

Xi Jinping had vaulted into the role of acting governor in Fujian province to replace a figure tarnished by corruption, before in 2002 he was elevated to party secretary of booming Zhejiang. There, he became friendly with Henry Paulson, who was Goldman Sachs’ boss, then US Treasury Secretary, and who has described Xi as “the kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line.”

Xi’s second wife Peng Liyuan is a famous singer, who became a national figure as part of the People’s Liberation Army’s top musical troupe. When Xi joined the PSC in 2007, I asked people at a Beijing bus stop about him and they shook their heads in puzzlement until I mentioned Peng. “Oh, that’s what her husband does…”

How did Xi get himself over the goal line then, in 2007, when his course towards the leadership was set – despite lacking significant national public awareness even of who he was?

China is of course marvellously unique. But it is by no means unique in harbouring a black box in which decisions are made, or from which leaders emerge. This was in fact the verb used in my own youth in Britain, before the Conservative or Tory Party adopted a more democratic constitution. The “grandees” as they were usually styled of the party – aristocrats, industrialists and landed gentry – would meet informally for a weekend at an ancient country house, from which the next leader “emerged” to speak with the waiting media.

Xi had a number of factors running in his favour. Including that he did indeed want to do stuff. He had grown up in Zhongnanhai. He had emerged as a leader during his time in the Shaanxi countryside as a “sent-down youth”. His father was known for his consistency and resolution as an economic liberal, and for his party loyalty despite being unfairly targeted. Xi also fits the physical bill for leadership. He is an imposing 1.8 metres, about six feet, tall – taller for instance than the person he last year described as “my best, most intimate friend” – Vladimir Putin, though not as tall as his biggest rival Bo Xilai, who was portrayed at the end of his TV trial, as he was sentenced, diminished beneath two towering policemen who must have been brought in from afar, each almost certainly standing nearly seven feet tall. Xi had presided over a ramping up of economic growth in two lively coastal provinces, Fujian and Zhejiang. He had twice – in Fujian then Shanghai – succeeded corrupt leaders and cleaned up after them. He appeared utterly dependable.

And he has throughout his career had luck – that crucial quality for success – on his side. He was born into communist royalty, and constantly reminds people of the importance of having such “red genes.” He was in the right place – based next to Shanghai – when a temporary new party secretary was needed there for that high-profile job. He was also well positioned subtly to contrast his own rising sense of the need for decisive, centralising action to respond to a widespread perception within the party of dangerous drift under his predecessor Hu. And when Bo Xilai, another princeling, emerged as a powerful rival, Bo’s wife Gu Kailai poisoned her English fixer and the whole Bo project imploded, with him being jailed for life – albeit at a public hearing that failed to provide any convincing evidence for the charges. Great good luck for Xi.

Hu’s personal inclination might have led him to push as his successor Li Keqiang, a leader in his own tuanpai, reform-inclined faction. But Hu’s core skill was as a chairman with a brilliant capacity to summarise the sentiments of a committee and to pursue that conclusion. He thus enhanced the informal process of consultations that had tended to precede major decisions. Xinhua news agency has described these as “face to face” consultations, especially with the outgoing PSC members but also more broadly within the Central Committee, to gauge party sentiment – both to ensure the right people and policies are announced, and as a management tool to ensure ultimate decisions are well accepted by those who count.

Party elders are inevitably part of such consultations, and among them Hu’s own predecessor Jiang Zemin would have played an important – possibly decisive – role. Jiang headed the “Shanghai faction,” and was also something of a godfather to the princelings more broadly. Xi was becoming central to both. Jiang had been chosen by Deng as his successor due in considerable part to his firmness in keeping control of Shanghai during the 1989 student protests. Jiang would have talked quietly to other opinion leaders in the party and in the army, suggesting that they strongly consider Xi’s qualifications to succeed in this Chinese Game of Thrones. After the debacle at the 15th party congress in 1997, when Xi received the fewest votes for the 151 alternate members of the Central Committee – probably because of a minor rebellion against the imposition of princelings, and at a time when the Youth League was ascendant – nothing would be left to chance in future “elections.” After he walked into that Great Hall room ahead of Li Keqiang in 2007, ultimate power was his to lose, and he has not taken a backward step since.

Luck as a factor pulled back Li Keqiang, who had come from a far more modest family background, as well as emboldening Xi. Not only party strongmen but also some of the broader public recalled the three mass-fatality fires that had occurred in Henan during Li’s tenure as provincial governor and party secretary there.

Cheng Li, director of the John L Thornton Centre at the Brookings Institution and the master mapmaker who most persuasively charted the role of factions within the party said astutely in 2007: “By selecting Xi as one of the two top candidates for his succession, Hu not only extends his own power network, but also undercuts any potential criticism of his political favouritism for tuanpai leaders such as Li Keqiang. Hu’s objective is to avoid the emergence of clear divisions and conflicting interests between princeling and tuanpai leaders, between the coastal region and interior provinces, and between the advanced economic sectors and the social groups that have lagged behind during the reforms. Accordingly, Hu allowed Xi to be in charge of party affairs and Li to be more involved in economic administration… If Xi were to succeed Hu Jintao as secretary-general of the Party in 2012, Li might well be named the successor to Wen Jiabao as Premier.” And so it proved. What even Cheng Li didn’t anticipate, was the rapidity with which Xi went on to expunge factions within the party – or to expunge them within their previous formats. Taizidang and tuanpai delineations have faded into history, and with them, a core source of potential challenge to Xi’s own personally-based power, which leans for support instead on those who proved adept and loyal to him as he ascended the hierarchy. His favoured advisors include Liu He, the economic policy kingpin, and Wang Huning – inventor of the “China dream” – who underlines Xi’s continuity with former leaders since he also worked prominently with both Jiang and Hu. Both Liu and Wang are now on the PSC.

No one expects a senior Chinese cadre to audition for promotion or to publish a manifesto. But Xi undoubtedly began to indicate quietly at this time, within party precincts, his likely priorities: maintain broadly, the pace and momentum of the reformed economy while seeking to revive the state sector; purify the party, purging corrupt elements and reconstructing it as the vehicle of China’s rejuvenation; and later, after Bo’s arrest, reviving the glorious traditions developed under Mao Zedong – shamelessly harnessing the red cultural tide summoned by Bo in Chongqing.

Now, Xi in power.

Since ascending, Xi has not felt constrained about promoting his views or “thoughts” – which essentially comprise a clever incorporation of those party strategies that have appeared successful over the last seven decades of power, into standard Leninist doctrine as amended by Mao. About 6.4 million copies of his two-volume book “The Governance of China” have been translated into 22 languages and printed and distributed – a safer word to use than “bought.” They comprise 178 pieces – chiefly from speeches – organised thematically, and illustrated with photos of the leader “at work and in daily life.” All party members are being required to study it. People’s Daily describes it as “the most influential book written by a Chinese leader” since Mao Zedong’s death. Yet it remains unclear, beyond fairly routine party verities, and beyond a clear eye for improving process by enhancing upwardly directed accountability, whether Xi has a program or a goal. He has a dream, a “China dream” – a dream actually, of China awakening to its opportunities. But its narrative remains blurred, rheumy. Xi certainly likes to control – the economy, public debate, all spheres – but to what ultimate end, is still being unravelled. He certainly talks more passionately about control, identifying six “false ideological trends, positions, and activities” emanating from the West: constitutional democracy; universal values; civil society; economic neoliberalism; Western-style journalism; and promoting historical nihilism by emphasizing the mistakes of the Maoist period.

We have had Xi’s thought on Socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era enshrined in both state and party constitutions, we have centres dedicated to studying such thought blooming on campuses around the country. A year ago I watched a film, Amazing China, required viewing for danweis in Beijing at least, which was chiefly about Amazing Xi, filmed speaking seemingly everywhere.

Now we have, released by the party’s publicity department in January, the Xuexi Qiangguo app, nicely punned between “studying our powerful country”, and “studying Xi”. This has become the most downloaded app in China, aggregating articles, videos, speeches etc about Xi and his Thought. Yesterday when I looked at one on a phone, every page view had a different picture of Xi at the top. The South China Morning Post has explained that “users must sign up with their mobile numbers and real names. Study points are earned by users who log on, read articles, make comments every day and participate in multiple-choice tests about the party’s policies. Cadres across the country are now required to use the app every day and accumulate their scores.” It is designed to be a super-app, as Tencent’s WeChat has become. Xuexi Qiangguo allows users to send each other messages, and to send virtual red packets from Alipay wallets. It also supports video conference calls. A new feature will allow users to redeem their “study points” for gifts. High app scores may boost a young party member’s marriage opportunities, a Chinese friend of mine believes.

The massive show at Beijing’s Exhibition Centre on the eve of the 19th Party Congress in late 2017, to mark the glory of “Five Years of Inspiration and Advancement,” underlined the extent of Xi’s power, the extent to which he now incorporated the party. Its entrance was flanked by red banners proclaiming that the party is “tightly united around Xi Jinping as the Core”.

A glass case in the exhibition displayed no less than 16 books authored by Xi, and nearby were commendatory quotes about the kind of leadership the party needs – citing Engels, Lenin, Mao and Deng, stressing the need for the centralisation of authority. Mao asked in one quote: “Can a walnut have several cores? No, it only has one.” Alongside, Chinese “netizens” – posting on social media – lavished praise on “Xi Dada” – “Uncle Xi… the good chairman of the people. He thinks of the people all the time… he carries the expectations of the laobaixing (the ordinary folk)… We feel assured with such a person holding the helm.”

There were hundreds of massive photos and videos of him throughout the exhibition, leading the way in every sphere of life, from the military, where he had just become commander-in-chief wearing combat greens, to the arts, where his erudition about the ancient classics was cited. Even artifacts such as a pair of army binoculars once used by Xi to view a PLA exercise, were on honoured display. In the many photos of him with ordinary people, he appeared more natural and relaxed than with his peers – which was also a facet of Mao Zedong. The other six members of the PSC had mere walk-on parts. The message was that the Chinese state was now contained within the party, rather than the reverse. The show cited Xi presiding over 38 meetings of leading small groups to champion unspecified “reforms.” The exhibition showed Xi sitting next to Barack Obama at a conference organised by Obama to reduce nuclear proliferation, stating that Xi “provided guidance on this issue.”

Women in uniforms like flight attendants’, hosted guided tours of the exhibition for special party groups, underlining important breakthroughs of the last five years. One told her group that “international conferences hosted by China” such as the Belt and Road Initiative launch “have fully illustrated the greatness of China, and its ability to influence the world by hosting them.” This is consonant with what those tour groups see on TV almost nightly. When Xi is shown with foreign leaders, they are often filmed entering the Great Hall and walking down an interminable red carpet while he awaits them with a special expression he has cultivated, of distance and reserve. When he emerged as party chief in 2012, he appeared to me to have an open face. This expression shifted towards a Buddha-like self-containment, and then by the time of the 19th National Party Congress, a more palpable disinterest. Those foreign leaders, awed by the environment, will often bow as they face Xi. He does not step towards them, nor bow in return. He rarely eyeballs them during the inevitable ensuing handshake. Chinese TV viewers of these receptions are put in mind of ancient tribute-state relationships. A party member at the exhibition, who said he was a businessman but would not give his name, told me that he was impressed with “the new thinking that China could not have contributed 10 years ago.” He said: “Like a general manager of a company, a national leader who is open-minded, including to new technologies, will provide good guidance. China is not conservative, as it was before.” Xi, he said, “is a leader of outstanding personal charisma, that’s why he is the Core of the party, the country and the people.” After years of experimentation, he said, “the international community is now studying the China model.”

The section of the exhibition that drew the biggest crowd, even ahead of the largest area which featured Xi’s guidance of the People’s Liberation Army, was the anti-corruption campaign. The feared CCDI had pursued 1.41 million cases in the last five years, it said, with 54,000 cadres punished through the courts. Pictures under a general heading “Punish the few, educate the mass,” showed the hangdog-looking guilty – the latest target, Politburo member Sun Zhengcai alongside the biggest “tigers” bagged by the campaign, Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang. Cai Xiyou, the former Sinopec head and a Zhou associate, was portrayed weeping. Xi was shown urging “maintain high pressure on corruption.” His resolution on this goal clearly commended itself to Hu as well as to other party elders. Xi had urged a party conference on discipline and the temptations of corruption back in 2004: “Rein in your spouses, children, relatives, friends and staff, and vow not to use power for personal gain.” Hu, echoing Xi’s concern, said in his last term in office that failure to eradicate corruption could “deal a body blow to the party and even lead to the collapse of the party and country.” A slogan at the 19th congress exhibition said that what is “bad luck for the corrupt, is good luck for the Chinese people.” Xi showed that he is a risk taker, by tackling “tigers” as well as “flies” in his loyalty campaign, especially in removing the entire network of security and petro-chemical godfather Zhou Yongkang. A caption of a photo at the show, stressed that by snaring powerful targets, “a major hidden political risk was eliminated” – without indicating whose political success was at stake, though readers might have hazarded a guess. Xi has of course gone on to establish the National Supervisory Commission, an extra-judicial body that extends to every person employed by the government, the same disciplinary regime that the CCDI has imposed on the party.

Rod MacFarquhar, the great sinologist who died last month, noted that “Xi Jinping is only the second leader clearly chosen by his peers. The first was Mao Zedong…” Before Mao, the Soviet Union’s Comintern in effect did the picking, after him Deng did. And Mao had himself brought back Deng from banishment as Zhou Enlai lay dying. This factor of beating out competitors adds to Xi’s sense of legitimacy. MacFarquhar said: “Xi is not primus inter pares like Jiang and Hu; he is simply primus.” He and the party have studied the fall of the Soviet Union intimately, and have concluded that the cause was not inadequate opening but excessive opening or glasnost; that it was not inadequate perestroika or economic reform, but reform that tugged the reins away from the party; that it was not a failure to learn from and step away from the tyranny of former leaders like Lenin and Stalin, but a failure to uphold these leaders’ reputations as core founders of the party and state.

A crucial source of Xi’s power is that he is not a pragmatist, he does not subtly seek to, say, “keep the PLA onside” by nationalist promises, he does not wake in the middle of the night wondering why he’s where he is. He is a true believer. As with religious belief, its truth is patent only to those who share the faith. And to a degree, only the high priest – the emperor, the chairman of everything – truly comprehends the transcendent source and meaning of such power. Mao’s doctor Li Zhisui said that when Chiang Kai-shek died, Mao was inconsolable, saying that he was the only other person in the world who truly understood the burden of ruling China. Xi sees the party as incorporating all the best of China, past present and future, and himself as incorporating the party. Having as a catchphrase a dream is somehow appropriate for a person with such an ultimately mystical understanding of authority. Xi has given various accounts of that dream, most fairly abstract. His grandest, came soon after his original election as party secretary, as he led the Politburo Standing Committee round the Road of Rejuvenation exhibition at the National Museum on the east side of Tiananmen, where he said: “I personally believe that achieving the great revival of the Chinese race is the mightiest dream of the Chinese nation today.”

Now the party.

The party, then, is the prime source of Xi’s power. He has removed many of the restraints on its rule, and thus of his own exercise of power. Whether manifested through religious loyalty to Islam in Xinjiang or to Christianity in say Chengdu, whether perceived in the human rights lawyers who formerly defended China’s marginalised communities or individuals, or whether expressed by Liu Xiaobo, the great Anti-Xi, what Xi’s rule enunciates is that alternative templates, opposition, even criticism alone, comprise subversion of the state, of his version of China itself.

China has become the party. And the people of China are accountable to the party, and to him, not the other way round. When this October 1 we recall the 70th anniversary of the declaration of the PRC by Mao in Beijing, there will be no great national celebration spilling onto the streets. As always with such events, the people will not be invited to join. I was there in Beijing for the 50th, and people who lived along the route of the military parade were told to watch it on TV, not even look out of their windows, or they risked being shot by army snipers.

I have wasted too much time as a journalist in second-guessing where Xi seeks to reinforce his and the party’s “legitimacy” – including say in raising living standards, in boosting China’s global authority, in highlighting the modernisation of the PLA, or in underlining the “one country” in the “one country, two systems” formula. This, I now realise, is not, perhaps never was, a core concern for Xi. He is concerned for the integrity of the party itself, for its self-belief. Thus his first-term focus on discipline and loyalty. In some analyses, “legitimacy” is perceived as equating to power. But the party’s power does not derive from its legitimacy, except insofar as it seized control of China by its force of arms. It does not waste much time in formally justifying – or legitimising – its rule, in part because that very word implies a high concept of legality and of the law, which the party of course subjugates in China. In its broadest sense, erosion of legitimacy in the eyes of the general population, as opposed to the perception of the party and its own paramount leaders, is seen as likely to be triggered by a severe and prolonged economic downturn or by a failed military adventure. But the party has already survived horrific economic and humanitarian disasters under Mao and a military failure – against Vietnam – under Deng. If Xi were indeed seriously concerned about his and the party’s apparent legitimacy, he might be seeking to cement his nationalist credentials by supervising detailed plans to conquer Taiwan, say, or in the economic realm by freeing up new core sectors of the economy to private sector involvement. He may end up doing both – I believe it highly unlikely – but not, I believe, because he feels any need to justify himself or his party to the rest of China or to the wider world. Especially once Jiang Zemin, the most important party elder, passes away, Xi will become even more palpably self-legitimising.

He explained to the 3,000 officials gathered in the Great Hall of the People to mark the anniversary of the launch of China’s reform-and-opening last December, the true lessons to be learned from those 40 hectic years: “First, the party’s leadership over all tasks must be adhered to,” he said, “and the party’s leadership must be incessantly strengthened and improved.” He contined: “It was precisely because we’ve adhered to the centralized and united leadership of the party that we were able to achieve this great historic transition.” The party’s socialist path had been “totally correct,” he declared: “Let contemporary Chinese Marxism shine even more brilliant rays of truth.” He had previously stated: “East, west, south, north, and the middle, the party leads everything.” He has told China’s journalists their “surname is Party.”

The great Australian sinologist John Fitzgerald points out that an important question that relates to my topic tonight, is who owns sovereignty in China? It is the party that, again, sees itself as the sovereign power. The people of China have never been allowed to seize the sovereignty theoretically handed to them by the abdicating Manchu dynasty 107 years ago. And once again, Xi incorporates the party. In Australia, in comparison, sovereignty is shared in equal measure among the nation’s citizens. Lenin insisted that a vanguard party represented the people because they lacked the capacity to stand for themselves. China’s is also such a vanguard party.

Some in the party – including those whom Mao overthrew during the Cultural Revolution by redefining his power as chaos – have over half a century puzzled as to the sustainability of this template. The “intra party democracy” under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao spoke to such concern. Cadres began electing one another. But this experiment failed, in part overpowered by rivalries and jealousies. If the party couldn’t be democratised, the alternative – pursued by Xi – has been to make it more assertive and Leninist. Instead of through accountability, cadres – especially local officials – are restrained by campaigns, by anti corruption machines. Myriad goals are set, but it becomes clear to alert cadres which have priority. For instance, in Xinjiang today this will be perceived as: no “incidents.” Every other element or goal of administration – including those that might limit or distract the overwhelming force and the massive incarcerations involved to ensure “no incidents” – must be sublimated. And as in the Soviet Union, the communist party in China too – also Leninist – is a multiplier of power, a power-enhancing machine.

The manner of Xi’s exercise of power is thus consonant with the source, or sources, of it. It is built on the sacrifice of martyrs, on the founding fathers, the Long Marchers like his father. It requires purity of thought, full-hearted loyalty. Central Beijing is itself being purged of distractions. The party had earlier destroyed the city’s popular temples. Now, in the last couple of years, all small-scale, popular noodle cafes, florists, bars, all-night stores, indigenous commerce, have been razed, expunged within the third and most within the fourth ring-road. The everyday is being eliminated, to be replaced by a new sense of the central city as a place of party purity, following its successful purging. The government bureaucracy is being shifted to Tongzhou in the city’s east, and ultimately the aim is to shift state owned enterprise HQs, universities, hospitals, and other research institutes out to Xiong’an, the vast new city Xi is personally planning 100 km to the south-west.

Xi grew up to replay constantly in his mind the sutra, “Don’t forget the party’s original vision.” He seeks to extend those moments of clarity until they spool through the nation’s dreams, and its waking hours.

His source of power can be reversed or cut off. The easiest way is for him to lose authority within the party itself. But when I scanned through my binoculars in the Great Hall, the group on stage at the conclusion of the 19th party congress, it was palpably the entire power elite, including even Deng’s son, Deng Pufang, who stood to applaud an indifferent-looking Xi. They felt they had no alternative but to get behind him, however much they might have had to do so through gritted teeth. Even if they started to talk critically to others in the elite, he would know in an instant, such is the scope of the surveillance tools at his disposal. So I’m not betting on this happening any time soon. Ordinary party members have since the abolition of term limits – viewed widely as a great scandal – and the US trade war begun to question Xi’s wisdom. But beyond harbouring questioning thoughts, they have little choice but to keep their heads down. Convulsive events within or without – a debt-triggered recession, say, or a military invasion of Taiwan that leaves China isolated – might provide embryonic party rivals with the peg they need to build sufficient support to take to elders and appeal to replace him. But these are as yet exotic and remote prospects. As yet.

Finally, what might the Xi phenomenon mean for the future? The centenary of the party is approaching soon, in 2021, and might tempt Xi to over-reach, but I feel that’s unlikely.

The emergence of Xi and Xi-ism is a very special development for China and the world, of that there is no doubt. I would not have been giving this talk on Hu Jintao in say 2008 even though he then presided over those impeccably organised Olympics, which many out-of-town reporters described as “China’s coming-out” to the world. Even then, Xi had been given as part of his OSC responsibilities, special Olympic oversight.

The high intensity of Xi’s rule, the dogmatic belief he demands, the deeply personal nature of his control of China, seem unlikely to last for the further decades that he appears to anticipate. He has eschewed even considering a successor, understanding the vulnerability that this injects but in another sense adding to that vulnerability since all in the next generation’s party elite may well be dreaming of ultimately displacing him. He may step aside from his formal positions yet remain assured of his continuing ultimate authority, by dint of appointing only personal loyalists, as was Deng. He has assumed greater personal power than Deng though, and a higher profile. But it is becoming ever harder for a single figure to take credibly and intelligently all the key decisions in a country whose governance is already made harder by dint of its not being federal, unlike every other nation in the world of its size. And just as Xi claims for himself and the party the credit for all that is positive, the challenges and the problems are also more likely to be rooted back to him – as we are seeing now in those signs of unease among party members concerning the US relationship.

Beneath all these potential sources of disruption of Xi’s power, lies the culture of China, the ancient, familial yet also individualistic, a culture that quietly resiles from the expectation of continuing to march to the sound of the same drum. The emerging social credit system that rewards and punishes according to one’s real and virtual world behaviours, typically encourages uniformity and discourages individuality and risk-taking entrepreneurship along with routine anti-social or anti-party behaviour. But as we’ve seen over the millennia, including the eras of foreign dynasties and the more recent “century of foreign humiliation,” China, its culture and its people, remains alive, distinct from those who seek to subsume its sovereignty.

Maybe as people travel more, at home and abroad, as they study internationally, they will start to lose patience with their constraints, which under Xi have become more palpable. The coming generation is already becoming detached from its parents’ sense of profound, automatic gratitude to the party for the surge in living standards they have enjoyed.

In the meantime, people in China and without will need to learn how to live with this Xi phenomenon, with a China more deeply enmeshed than ever with the party that feeds off it. A year or so ago I wrote on my laptop in Beijing a draft of a feature on the party, and got distracted by more pressing stories. When I returned to it a fortnight later, someone had written on the top in a strange font, in English, the words: “The glorious communist party of China, always with you.” Someone had either got in to my flat or office when I was out, or hacked in online. So yes, we do have to work out how to relate to this party, and to its for-now irreplaceable, irrepressible leader – while becoming more mindful of just how unique is it, is he, and how Xi and his party relish playing, to use a soccer analogy, a pressing game.

While we are now starting to discover how predictable life in China is under Xi, at the same time and for the same reason we are left wondering more than for any leader except Mao, what will happen after him. Might indeed the party which, at first unknowingly, placed all its eggs in the Xi basket, face a less certain future following the personalised, centralised governance that is Xi’s own hallmark? What if he fails, in some palpable manner, before he is ready to leave the stage? He is set on making the party irreplaceable, but mere mortality demands that his own rule is finite. Would a Xi-less party retain meaning? If so, what might that comprise?

Xi’s rule raises such questions even as it answers others.