The aftermath of COVID-19 will test Australia’s ability to fulfil obligations in the Pacific. It will also test its understanding and use of soft power in the national interest.

People in the Pacific sometimes refer to Australia as “big bro” or “papa” because of Australia’s relative size, historical involvement and influence in the region. It follows that they would probably want Australia to step up. Particularly in places like PNG where the bond from colonial times is still strong, despite mixed memories about the taim bipo (pidgin for theyears before independence in 1975).

In traditional Pacific societies, respect for local culture overrides Western pragmatism. As a result, a practical, rules-based approach to aid is met with attitudes as conflicted as the memories of the taim bipo. Reliance on aid sits uncomfortably with Pacific islanders’ sense of independence and identity. An economic-rationalist approach to aid which makes perfect sense in the West sometimes conflicts irreconcilably with cultural imperatives, such as the need to look after extended families. Programmes which ignore those cultural imperatives sometimes fail or are ineffective and waste resources.

In the Pacific, everything is intensely personal. Melanesia’s wantok system is built on complex webs of mutual obligation which flourish beneath an overlay of parliamentary democracy and the rule of law. It holds societies together in ways that are impenetrable to outsiders.

Polynesia’s hierarchical, chiefly system provides more transparency to outsiders. But it is still founded on wide-ranging reciprocal obligations of kinship which are counterintuitive to modern western individualism.

However, systems adapt. Amongst the hundreds of languages of PNG, wantoks were people who spoke the language of the same ethnic group. The concept is now more fluid. Wantoks can be people who went to school together, work together or even people who spend meaningful time together, regardless of their linguistic or cultural background, including across national boundaries.

Spending time offers outsiders a pass into the system. Importantly, it creates an obligation which Pacific islanders can repay. They can never repay a new road, or airport or institutionally-strengthened financial sector, all of which come with strings attached to our rules-based system. One of the clear messages from the February 2020 Whitlam Institute report Pacific Perspectives on the World was that the quality of Australia’s relationships matter more than the quantity of aid or trade.

Spending time involves investing in personal relationships with mutual obligation and it might just help Australia with its attached strings in an environment of competing obligations.

Good relationships have a fragility about them that you just have to accept. That fragility is only countered by authenticity and trust. Some Australian officials, those who will be responsible for delivering the Pacific Step-up, will be uncomfortable with this approach. On the surface, it smacks of Public Service Code of Conduct conflict of interest or even worse, a betrayal of country and the ugly perception in Canberra that they might have “gone native”.

Of course, showing respect for another culture does not mean you have to adopt it. Even so, some of the undoubtedly highly qualified people Australia will send to step up will be uncomfortable with Pacific culture or some of its attributes, making personal relationships difficult. Perceptions about living conditions, hygiene or practices such as chewing betel nut or drinking kava can be hard to see past. They are reinforced by the way Australian Government personnel and their families are isolated from the local populace in razor-wire-encircled compounds in some places.

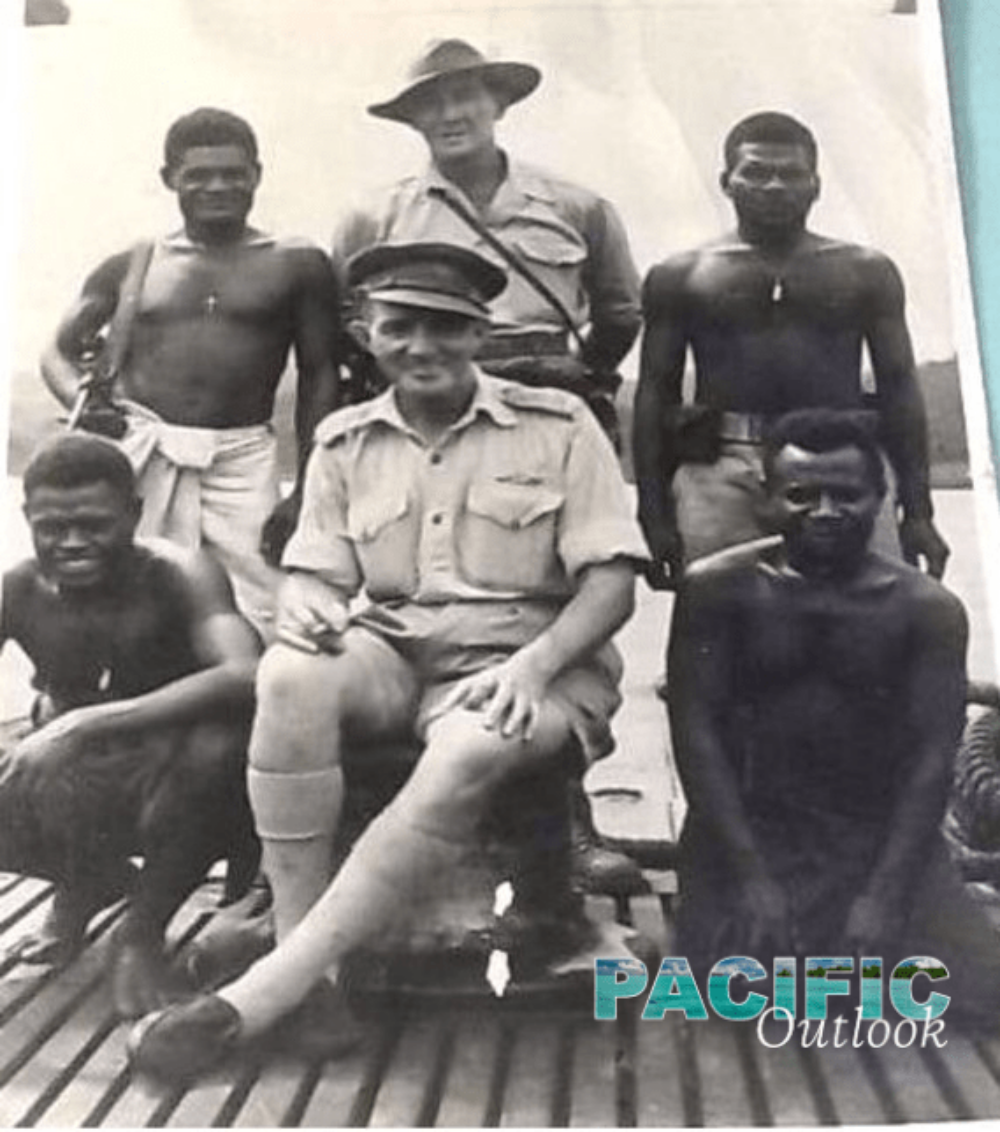

Yet the approach has worked in the past. It used to be bread and butter for some of our special forces, before they were used the way they have been in the Middle East in recent years. Australia’s WWII Coastwatchers (Remembering the “wasman” of Papua New Guinea) were adept at this and changed the course of the Pacific War from behind enemy lines, but were never seen as disloyal for the bonds they formed with Papua new Guineans.

Elsewhere, members of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam, like Captain Barry Petersen, showed how it could be done amongst the traditional societies of the Montagnards in Vietnam[TNC1] . (Though the CIA thought he had “gone native”.)

They successfully balanced loyalty to country with personal loyalty, while maintaining mission focus. Not everyone can do this. It is, however, a sensible and pragmatic approach to achieving a desired effect or goal.

But that was war and they were soldiers. Actually, many of the Coastwatchers were not or were given rank so they wouldn’t be executed as spies. This did not help some. The fight against COVID-19 has been likened to war and the effects on the societies of the Pacific could be severe if the virus were to spread and the economic effects are already hitting hard.

Now is the time to think about the aftermath. There will be lots of competing views about what Australia should do, where and in what order. But without the right people efforts will again be fraught. DFAT’s Office of the Pacific should be looking for those people now. There isn’t a check list for this, but the ability to form authentic personal relationships while achieving the Australian Government mission will be key. Cue the Ella Fitzgerald classic ’tain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it.

AUTHOR

Paul Slater is a former Pacific desk officer in Defence, Liaison Officer in Papua New Guinea, and Bougainville Peacekeeper. He is now working with Place Mamboo Inc, a not-for-profit seeking meaning for today’s veterans through connection with the people and places of our wartime past.