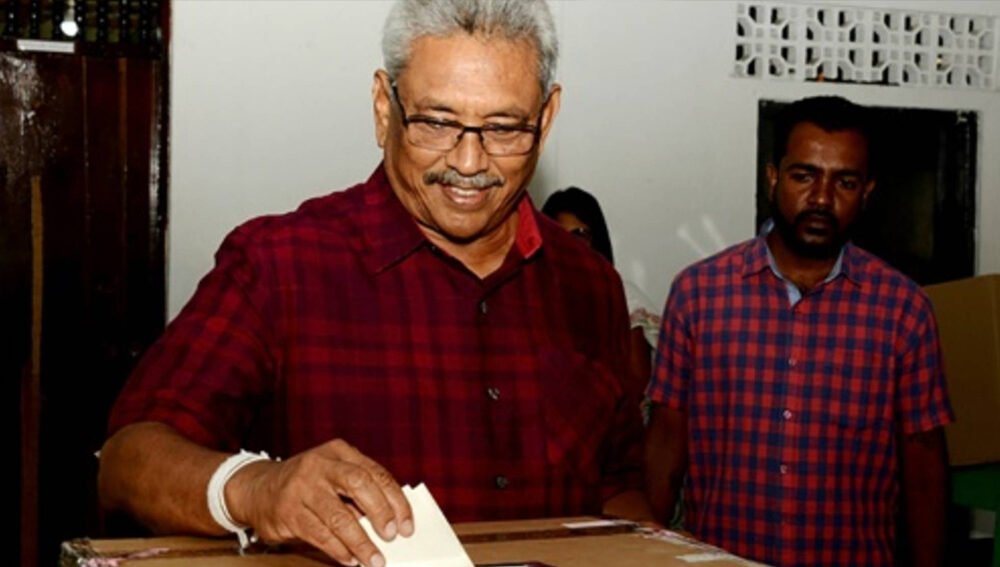

On 17 November 2019, former Defence Chief and brother of the former two-time president Mahinda Rajapaksa, Gotabaya Rajapaksa won the Sri Lankan presidential election with a landslide victory. Gotabaya focussed his election campaign on a national security narrative after the Easter bombings in April this year by ISIS-affiliated terrorists, promising to restore stability in the country. In his previous post as the Chief of Defence, he was responsible for ending the 25 year-long bloody civil war by defeating in 2009 the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam), a Tamil separatist movement seeking autonomy in Northern and Eastern parts of Sri Lanka. This however, garnered him widespread criticism regarding extra-judicial killings and other alleged war crimes in doing so.

This election was a polarising one as Gotabaya’s victory was supported by the Sinhala Buddhist majority, posing concerns for Sri Lanka’s future reconciliation efforts between the Sinhala Buddhist majority and the minority Tamil population. Regionally, geopolitical relations will also need close attention as the China-friendly Rajapakasa brothers have accepted Chinese loans in the past to finance key infrastructure projects even as Sri Lanka’s debt to Beijing balloons. This may likely cause concern for neighbouring India whose strategic competition with China is intensifying. Overall, Rajapaksa’s victory is a cautious one. With his election there are renewed hopes for increased security from extremist terrorism. However, concerns regarding the escalating ethnic and religious tensions in the country as well as a stuttering economy remain acute.

Nicknamed the “terminator” because of his ruthless efforts in crushing the Tamil tigers 10 years ago, Gotabaya, during his campaign, capitalised on the intelligence failure under the Wickremesinghe administration that led to the Easter bombings. He promised to crush religious extremism as he conducted a nationalist campaign focussing on national security, quite similar to the one run earlier this year in India’s national elections by Prime Minister Modi. His main opponent, Sajith Premdasa, the current Minister of Housing, Construction and Cultural Affairs from the incumbent United National Party (UNP), and the son of former Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premdasa, was not able to step out of the shadow of the seemingly incompetent government that failed to prevent the terrorist attacks. Ultimately, it was the impact of the Easter bombings that influenced the outcome of this election, and Gotabaya’s positioning as the man who can ‘get things done’ made him a more favourable candidate.

Still reeling from the civil war, the ethnic and religious divide between the majority Budhhist-Sinhalese and Tamil population has widened during this election campaign. The Rajapaksa brothers have been known to support clan based politics and the election results show that they are supported by the majority Sinhala community, while the Tamil dominated area of the Northern Sri Lanka preferred the more moderate Premdasa. The polarising nature of this election and Rajapaksa’s victory could possibly fan the flames of Sinhalese nationalism in the coming weeks and months. However, after his victory was announced, Rajapaksa assured in a tweet that he was deeply committed to serving all the people of Sri Lanka, not just those who voted for him.

Regarding the geopolitical outcomes from this election, the Rajapaksa brothers’ China pivot could be a cause of some tension in the region. Saddled already with a large Chinese debt as Mahinda Rajapaksa undertook loans to finance white elephant projects, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has stated that he plans to ‘restore relations’ with China if he won. The rise of Chinese influence in Sri Lanka has been a cause for concern for its neighbour India. Arguably, the most visible sign of this growing concern is the Chinese acquisition of the Hambantota port as a debt swap which also allowed for the expansion of Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean. Here too, twitter has calmed the waters, as Indian PM Modi congratulated Rajapaksa on his victory and stated that he looked forward to strengthening their friendship.

Gotabaya’s administration will need to provide a balancing act in how it governs. This applies to how it manages Sinhalese-Tamil relations and its relationship with India and China. For the former, the future of reconciliation needs an urgent push, as momentum under the previous Rajapaksa regime was notoriously slow and future efforts remain uncertain. For the latter, there needs to be a more sustained approach to how it manages its economic reliance on China. On the security front, Gotabaya has a proven record of success. What will be telling is how he fairs on the more sensitive issues concerning ethnic domestic policy and foreign policy accounts.

Teesta Prakash is a PhD Candidate at the School of Government and International Relations and Griffith Asia Institute.