The public discussion about Australia-China relations has taken such a toxic turn in recent months that some of our savviest and most sound China experts are choosing to steer clear, focusing their attention instead on the People’s Republic itself.

Enough is certainly happening there, as Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping pushes ahead on every front, to keep analysts ultra-occupied.

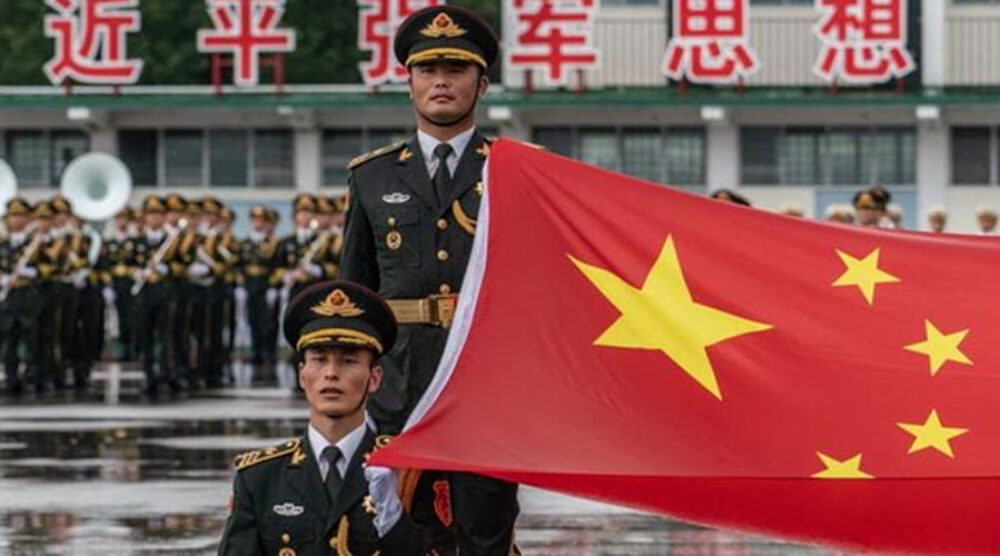

The centenary of the party – now clearly the most powerful organisation in the world – next month is China’s centrepiece event this year. Then in February next year the Winter Olympics will provide a more global platform for China to display its “rejuvenation”, underlining Xi’s conviction that “the East is rising and the West is declining”.

At the 19th party congress in 2017, Xi declared: “Our mission is a call to action. Let us engage in a tenacious struggle.” Consequently, China is changing at an extraordinary pace, driven by the fervour of Xi, more of a theocratic ruler than a conventional political leader, and also by the Xi loyalists who now comprise the entire cadre class – and who, as Kevin Rudd says, “are highly unlikely to be providing frank and fearless advice”.

But we hear from many influential Australians that our falling out with Beijing has resulted substantially from our failure to “engage”. As if our patient, personable and highly professional ambassador, Graham Fletcher, in his fourth posting to Beijing across 35 years, is tearing up the constant invitations to lunch at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or telling the Commerce Minister for the umpteenth time that he’s too busy to talk to him.

Fletcher and his team at the embassy and consulates around China are working their contacts to the full. But times have changed mightily, and those who have not been keeping up find it hard to understand how they have changed, and how much.

For instance, a fortnight ago Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox, himself a former diplomat, urged the government to deploy “negotiation, commonsense and diplomacy” with China. And Warwick Smith, who chairs the Business Council of Australia’s China leadership group, said: “I’ve been in and out of China for many, many years, and it shouldn’t be as bad as it is.”

They are both right, as usual. Diplomacy should work and it shouldn’t be this bad. But the past doesn’t provide adequate context for the current toxic turn. My own experience of living in Beijing as The Australian’s China correspondent from 2006 to 2008 soon had to be placed to one side, in terms of explaining to readers how far and fast Xi was changing everything, when I returned in that role a decade later.

Australian politicians and officials have been guilty of making careless comments, and good foreign policy certainly requires focus and co-ordination. We could and should do better on that front. But ad hominem attacks on Australian China experts, and claims that analysing China’s ruling party feeds racism, fuel ignorance when we need to know more.

“Government, military, society, education, north, south, east, west, and the centre,” Xi says, “the party leads all.”

What’s happening with China goes way beyond loose lips or protocol. And it’s affecting the whole world. It’s not an “Australian issue”. Concerns about China’s debt-diplomacy were at the fore as Samoa’s first female prime minister, Fiame Naomi Mata’afa, was sworn in last Thursday. And I’ve recently participated in intense webinars about China from countries as disparate as India and Chile.

Mild-mannered Fletcher – whose description of China’s commercial coercion as “vindictive” was all the more telling – is surrounded in Beijing by ambassadorial peers facing similar challenges. Last Thursday he attempted in vain to attend the Beijing trial of Australian Yang Hengjun, who has refused to confess to unspecified charges of espionage, saying: “There is nothing more liberating than having one’s worst fears realised.”

Feng Chongyi, a leading Sydney-based China academic and Yang’s friend, applauded Fletcher’s “heroic act”.

Two friends of mine also are in Chinese jails. Australian Cheng Lei, a convivial business host at state TV station CGTN, has been held for 10 months in a Beijing prison on bewildering claims of leaking state secrets. She has not been allowed to speak to her two young children or to a lawyer.

ABC journalist Bill Birtles, who had to leave Beijing for safety, revealed that at Lei’s most recent video call with the Australian embassy, “she was brought into the room blindfolded, masked and handcuffed by four guards, two of whom were wearing full PPE hazmat suits. She was made to sit in a chair with a wooden restraint affixed across her lap,” before blindfold and mask were removed.

Another friend, Claudia Mo, also a journalist as well as a pro-democracy MP, one of the many victims of the national security law created to subjugate Hong Kong last year, has been in jail there for three months charged with subversion — a life-imprisonment rap — merely for helping organise a primary election for democratic candidates.

The world has entered uncharted waters. Powerful countries have taken troubling turns before, but never one so globally engaged economically, so single-mindedly and effectively controlled, and so determined to create a new international order.

We should pay close attention rather than pursue heated arguments among ourselves, which broadly furthers Beijing’s aims. Australia can respond, but that requires grounded, contemporary understanding.

AUTHOR

Rowan Callick is a double Walkley Award winner and a Graham Perkin Australian Journalist of the Year. He has worked and lived in Papua New Guinea, Hong Kong and Beijing and an industry fellow with the Griffith Asia Institute.