By: Dr. Jenny Allen

Entanglement is a global issue facing the largest marine species, particularly large whales. Over 300,000 baleen whales are caught each year in fishing and boating lines, netting, or other floating debris. In Queensland, this issue predominantly impacts the humpback whales which migrate along the coastline, primarily due to shark-control nets or fishing gear. However, rarely does the average person witness this issue first-hand, let alone be in a position to actively do something about it. Yet this was the extraordinary position that the Griffith students of 2305ENV (Marine Megafauna and Planetary Health) found themselves in during their Monday morning field trip.

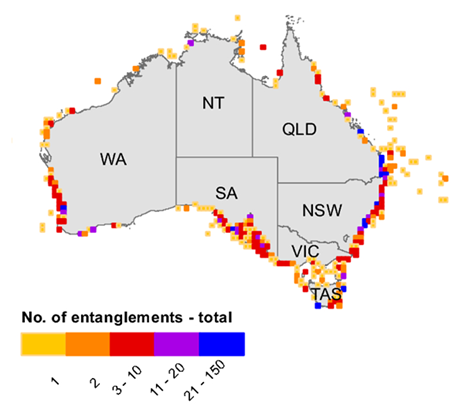

Total number of recorded entanglements for whale and dolphin species around Australia from 1987-2016 (Tulloch et al. 2020).

Every year, Griffith University partners with SeaWorld to take their 2305ENV students on the water to see humpback whales and learn about how they are studied by Griffith researchers. The first of three trips for the 2023 cohort of students occurred on the morning of Monday August 14th. The trip began with a pair of whales that allowed students to observe whale behaviours, practice taking identification photos of their tails (known as flukes), and enjoy seeing these animals up close. However, when the boat left this pair and found another whale by itself a bit further out, things got interesting. The whale began acting very erratically, barrel rolling, thrashing, and trumpeting (a loud sound made through their blowhole that often indicates stress). A glimpse of rope around the whale’s tail soon made it apparent that this whale had become entangled in some type of gear.

A photo taken by Griffith staff member Dr Jenny Allen of the entangled whale during the 2305ENV field trip aboard Sea World I. The anchor line is wrapped around the base of the fluke or tail, with the anchor itself weighing down the whale’s fluke.

The field trip quickly shifted into a rescue mission. Sea World contacted their disentanglement team, comprised of trained individuals with experience in helping to remove gear in these situations. Our job became to keep track of the whale and try to determine what kind of gear was caught on the whale until the disentanglement team. A swim across our bow allowed us to see an anchor being dragged behind the whale on a long line – likely discarded from a small recreational vessel in the area. While the whale was surfacing frequently and lifting its fluke, there were also several other groups of whales around. It was a challenge for our vessel to keep track of the whale and ensure that we did not mix it up with another whale – this is where the students were able to see how important visually identifying a whale using its dorsal fin and tail can be. Luckily having so many students on board meant that we had lots of eyes constantly scanning, and the students helped our vessel to keep up with the whale.

The clear identifying features of the entangled whale that helped us track the whale while we waited for the Sea World Rescue team. The top photos show the fluke or tail, which was entirely black (quite unusual for Australian whales) with several white lines marking the left side. The bottom photo shows the dorsal fin, which had very distinct white markings on the top which made it easily to quickly identify when it would come to the surface.

The Sea World Rescue team arrived, and our vessel moved into a supporting role – helping them to track the whale as they made their approaches to assess the entanglement. Disentanglement is a complex process that requires specialised tools and a great deal of training. There are teams all over the world that have developed effective ways of removing gear from large whales. Often the first step is to attach a large buoy to the gear, both allowing the team to more easily track the whale, as well as slowing it down to make approaches easier. Next, grappling lines are used that have a reversed blade attached. These will hopefully catch onto the rope caught on the whale and cut it. Sometimes this can take hours if there is a lot of rope or if it is wrapped around the whale in a way that is difficult to access. Luckily, the rescue team was able to remove the anchor very quickly. Once the anchor has been pulled off, the rest of the rope came off on its own. The rescue team made a few more close approaches to confirm that all the gear had been removed, which it had thanks to the team’s efforts.

Luckily for the whale and for our students, this entanglement had a positive outcome. This really highlights the importance and value of trained teams like the Sea World Rescue Team. Their expertise allowed them to handle the situation quickly and effectively, using techniques that have been developed by international experts in the field. It also emphasizes the degree to which we likely underestimate this issue for large megafauna such as baleen whales. The numbers that we have are only based on animals that are observed entangled in gear or found dead with clear evidence of entanglement as the cause. For every whale that is rescued, more are either never seen at all or seen and not reported, thus they are never counted in scientists’ estimates. This illustrates how important it is to accurately access these types of conservation issues so that they can be properly addressed.

The complex nature of entanglement as a human-wildlife interaction means that policy and legislation are where this battle is likely to be won. Implementing measures for whale-safe fishing gear may help to reduce the incidences of entanglement. For example, researchers are developing equipment that allows the majority of gear to be near the sea floor with buoys that can be triggered to come to the surface for retrieval. Monitoring tools such as WhaleAlert (an app that allows users to report whale sightings) improve documentation of entanglements, hopefully lowering the number that go unaddressed and uncounted. What we can hope for is that some of the 2305ENV students will be inspired by what they saw on their trip and eventually make their own contributions to this pressing conservation issue.

Recent Comments