This post has been contributed by Dr Allan Ardill, a lecturer in the Griffith Law School and a member of the Law Futures Centre

Student attendance

I often hear colleagues expressing frustration with student attendance in their courses and indeed I have registered my concerns about attendance too. Amongst other things, attendance is important for building the trust needed to teach students to navigate controversial content, or to develop technical problem-solving ability and skills. It can also be disheartening preparing classes when only a few turn up. For those of us who convened courses before the introduction of universal lecture recordings we remember the impact it had on a vibrant lecture culture where 90% of enrolled students would not only attend lectures— there would often be discussion and debate. After the introduction of the mandated recording of lectures I found numbers fell to as low as 25-30% of the enrolment by the second or third week. Attendance has remained relatively low even after the transition away from the lecture model to the COVID 19 driven workshop model.

At a recent forum discussing teaching and learning the ‘problem of student attendance and participation in university events’ was canvassed. The general sentiment was focused on changing students’ expectations about attending classes and events. ‘How do we get students to attend?’ After 40 minutes of this discussion, one colleague reflected on our collective frustration and suggested that ‘maybe it’s the teaching staff that need to reflect on their expectations’. That was a lightbulb moment for me. I realised at that moment, maybe we needed to rethink our desire for a return to the days when most students attended classes at university.

I have always kept student attendance records for the courses I convene to compare student attendance with final grades. I’ve typically done this comparison by way of histograms. But after that lightbulb moment, I decided I needed to know a bit more. So, I turned to correlation. Looking at the last two years I have found in the course I teach, that there is a weak but significant correlation between attendance and learning outcomes. For the record, this course is critical, conceptual, and inter-disciplinary.

This finding could be unique to the course I teach in terms of its content and design. However, I am now wary of being deterministic about the importance of student attendance for performance. This is something in need of further research and nuance because there are innumerable factors that might influence learning outcomes of which attendance is just one factor. Other factors might include the student profile in terms of socioeconomic factors, whether the course is mandatory or an elective, the extent to which it is theoretical or abstract, whether it is critical and/or interdisciplinary, and how students are expected to engage with the course (in-person, online, external, etc).

The data

Since we shifted to the workshop teaching model in 2021 (two hours of workshops per week per student) my workshops have been ‘strongly recommended’ but ‘optional’ for students. The course is otherwise available completely online. I provide both in person and online workshops at two campuses (Nathan and Gold Coast). All my workshops are recorded, and students can choose to do the course wholly online with no attendance. In 2021 the ‘average’ student attended 44.1% of their weekly workshops and in 2022 this dropped to 37.5%.

Most students do not attend all their workshops. Instead, students want to choose which classes they attend, how they attend, and when they attend. In addition, there is a significant minority of students (about 20%) who do not attend any classes. For most of these students (72%), no attendance is a successful learning strategy. However, this also means that 28% of the students who do not attend any classes fail the course (more on this shortly).

When attendance is correlated with final grades (measured as a percentage, not on the 7 point scale), I found a significant but weak correlation coefficient of 0.438731 in 2021 (n = 313) and 0.36128 in 2022 (n = 308). In other words, attendance can impact on performance, but it is not as important as the combined effect of other factors. Furthermore, a correlation does not necessarily mean the variable is a cause. So, for some students, attendance is more important than it is for other students because attendance is an important aspect of the way they learn. What is really important is the discernible connection between attendance and performance at the bottom end of the student cohort where students are most at risk of withdrawing or failing the course (see below).

Grades for undergraduate students who did not attend any workshops in 2021:

| Zero workshops attended | Fail | Pass | Credit | D | HD | |

| 3014LAW GC (n = 171) | 28 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 8 | 2 |

| 3014LAW NATHAN (n = 142) | 43 | 13 | 9 | 13 | 7 | 1 |

It is not clear to me whether lack of attendance causes poor performance or whether it is just an indicator of a lack of engagement. It could be both. There is definitely some connection. What I would like to know more about is the relationship between attendance and student engagement (the extent and way the student immerses themselves in the course). I do not have control over student attendance, but I can have an impact on student engagement by designing my course with that in mind.

Why students cannot always be expected to attend

Student attendance is a product of much more than just the introduction of new technology. The neo-liberal turn has had a huge impact on education and more recently the COVID pandemic has likewise had very significant impacts.

The corporate university and broader neoliberal economic policies since the 1980s have changed university study. Gone are the days when most students did not need to work while they studied, gone are the days of compulsory student unionism, campus cooperatives, and vibrant campus culture to be replaced by a culture of individual student consumers who often must work to fund their studies.

Attendance is driven by many intersecting marginalities including class, financial precarity, family/caring responsibilities, health and disability, racial discrimination, internationality, etc. The current housing rental crisis is not going to get any better and anecdotally seems to be a significant factor requiring my students to increase working hours thus preventing university attendance. Well before the housing crisis, students were either ineligible for Austudy or unable to survive on this inadequate form of government assistance for students. According to Mission Australia ‘A single adult living on less than $433 a week, before housing costs’ and ‘A couple with two children living on less than $909 a week, before housing costs’ will be below the poverty line. Many of our students fall within those ranges. Students are forced to work while they study at university and as such paid employment is undoubtedly the greatest barrier to attendance. Add to this the number of students with family and caring responsibilities, and health/disability barriers, rates of attendance are understandable.

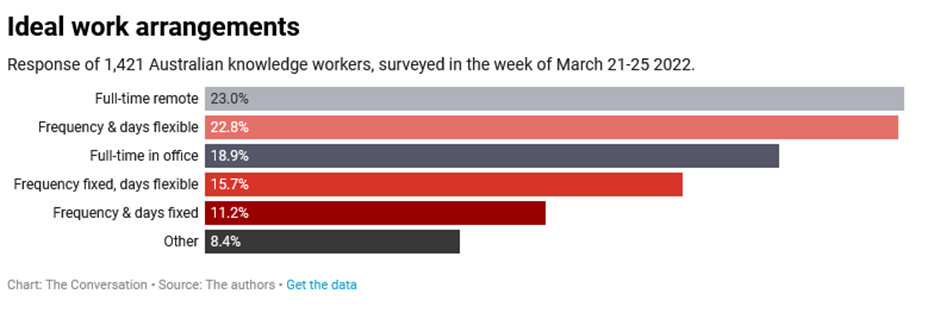

There is also evidence emerging showing that productivity lifted during the pandemic as people worked flexibly. What we know is that performance is linked with personal choice. Flexibility makes us happier:

“From the individual perspective, our survey strongly indicates those with the greatest flexibility were happiest. About 94% of those with the greatest flexibility said they were happy or very happy with this arrangement. This compares with 88.5% of those working remotely full-time, and 70.6% for those going into the office full-time.”

Therefore, with segmented post-pandemic work preferences and practices, we should not expect students to be any different. What we should expect is that our courses must provide genuine choice for students with an emphasis on engaging them regardless of the choice they must make to access education. This is consistent with Griffith Learning and Teaching Plans in particular student centred learning, and for me personally, a fundamental element of the accountability expected by feminist standpoint theory.

Attendance or engagement

As a standpoint theorist I should have been more attuned to the material conditions affecting the way students can engage with university and focusing instead on what I can do to make it easier for students to succeed. It is surprising how easy it is to fail to see how systems can be experienced from the perspective of others! It’s been almost 25 years since I experienced life as an undergraduate student, and conditions are vastly different today. An important reminder to be more accountable to those who do not share the same experience. Standpoint theory does not mean that the most marginalised and disadvantaged voice is automatically preferred, it requires that those voices are heard as the basis for a critical assessment of the structures instituting that marginalisation and or disadvantage.

Applying this to contemporary teaching and learning at university means educators should be more concerned with what we can do to facilitate student engagement rather than forcing attendance. Importantly, it means management should be wary of homogenising courses and more supportive of academics practising diverse teaching methods. Especially when making courses more accessible and engaging through universal design for learning principles.

Unfortunately, a recent study by the Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education found ‘little progress toward diversity and inclusion seems to have been made beyond aspirational statements’ at 39 Australian universities. Clearly, more needs to be done and the first step is to recognise the need for diversity in course design to accommodate the material circumstances our students face. Those material circumstances suggest there will be a mix of demand for no attendance (external), attendance online, attendance in-person, and hybrid courses. Our challenge is to design our courses to engage students regardless of the ‘delivery’. While there is little that is certain about the future of human behaviour, it is more likely than not we will not see a return to high rates of attendance whether in-person or online. We can only take responsibility for what we can control.

Recent Comments