This post has been contributed by Professor Leanne Wiseman, an ARC Future Fellow, Professor of Intellectual Property Law at Griffith University and member of the Law Futures Centre. Her current research expertise focuses on the intersection between law and digital technologies, with particular attention to balancing IP rights with genuine access to information. She is currently researching legal and regulatory responses to the international Right to Repair movement.

We all have things that are broken around our homes. Old iPhones, microwaves, fridges, washing machines or everyday consumer devices, such as our fitbits, tablets and computers. If we can’t fix them, they usually end up going into the rubbish and then ending up as landfill. Did you know that there are over 140,000+ tonnes of E-Waste generated by Australians every year?

Conscious of the ever growing pile of electronic waste going into landfill, many of us try to get our products and devices fixed, but it is not easy. Modern products are not being designed in a way that makes them easy to disassemble so we can replace batteries that have failed or parts that are damaged. In addition to design challenges, manufacturers, aware of how lucrative the repair aftermarket is for their products, increasingly employ a number of technological, legal and physical barriers to repair to reassert their control over the product throughout its life.

Manufacturers use a myriad of ways to keep us from fixing our stuff. Manufacturers not only restrict access to repair information but they also control through their end use licence agreements (EULAs) who can service and repair the products we buy and own. The spare parts are expensive or, in some cases, unavailable. Manufacturers also claim that if we try to fix the things we own so we can keep them in use for longer, we not only breach the manufacturer’s intellectual property rights in the embedded software in their products but we are putting ourselves and our privacy at risk.

The inability to repair the goods, vehicles and machines that we buy is increasingly and globally important as countries transition to Circular Economies. The inability to repair the things we own is not only a household problem. Our businesses, our hospitals, our farmers, our miners all encounter difficulties in accessing reasonably priced repair services and repair information about their machines and products that they purchase and own. During the Covid 19 Pandemic, we have seen the inability to access reasonable repairs and service information for life-saving medical devices, such as ventilators, putting patients’ lives at risk.

This inability to conduct repair or access repair information has given rise to an international Right to Repair movement and correspondingly legislative initiatives, that began in the United States in 2012 and has spread more recently to the EU and Canada. Put simply, the international Right to Repair movement has a two-pronged approach: empowering consumers with rights to repair their goods without going to an authorized agent or to choose to have their own third party repair their goods, and requiring manufacturers of smart goods, cars and equipment to make their diagnostic tools, manuals, and other repair-related resources available to any individual or business, not just their own dealerships and authorized agents.

The inability of Australians to repair their smart goods, cars, machines and equipment or to access repair or service information is having a significant impact on not only the Australian economy, but also its environmental future. Our Federal Government is concerned about our inability to have our faulty smart goods, cars and farm machinery repaired at a competitive price by a manufacturer, a third party or self-repair. It has begun to consider the role that a Right to Repair could play in the broader Australian economy and in its environmental future by tasking the Australian Productivity Commission in 2020 to inquire what a Right to Repair for Australians would look like. The role the Right to Repair can play in the Australian society and economy is in line with the Australian Prime Ministers’ investment of $167 million to an Australian Recycling Investment Plan which includes $20 million for a new Product Stewardship Investment Fund to accelerate work on new industry-led recycling [and repair] schemes and the passage of the Federal Government’s Recycling & Waste Reduction Act 2020.

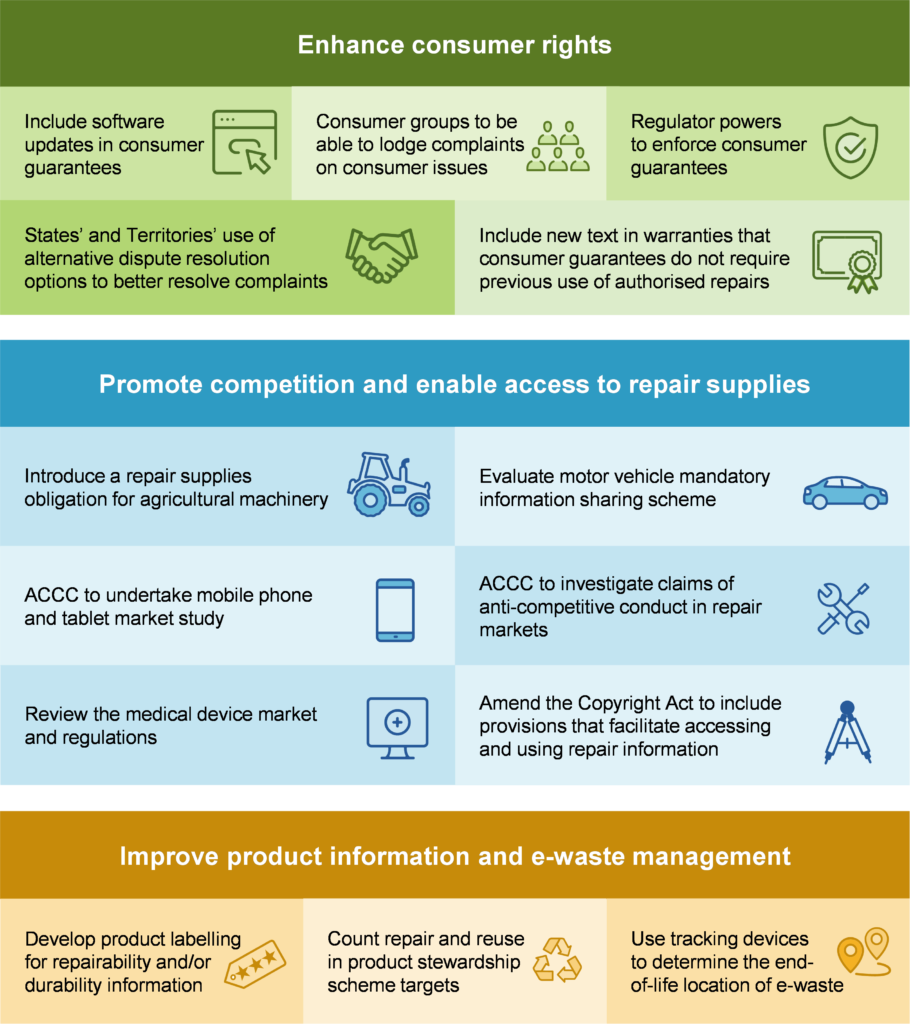

After a 12 month broad ranging inquiry, the Australian Productivity Commission handed down its final Right to Repair report on 1 December 2021 with some key recommendations that will address many of the ‘significant and unnecessary’ barriers to repair that are being experienced. It was recognised how multi-faceted the barriers to repairability were and it was acknowledged that any regulatory response needed a range of policies, including consumer and competition law, intellectual property protections, product labelling, and environmental and resource management.

A key raft of recommendations were directed at ensuring consumers are more aware of their consumer law rights but also acknowledged that manufacturers should also have obligations with respect to the repairability and service of their products. While it was recognised that consumers already have rights to have their products repaired, replaced or refunded, and to access spare parts and repair facilities, under consumer guarantees in the Australian Consumer Law, a number of improvements were recommended: including the obligation for manufacturers to provide software updates for a reasonable time period after a product has been purchased, to reflect the increasing dependence of consumer products on embedded software and requiring manufacturer warranties to make clear that they are not jeopardised if consumers do not have to use authorised repair services or spare parts.

Significant competition issues around access to repair information and services were identified in a number of markets, including agricultural machinery, automotive repairs and smartphones, tablets and medical devices. In each of these product markets, there were found to be several opportunities to give independent repairers greater access to repair supplies, and increase competition for repair services, without compromising public safety or discouraging innovation. The Australian automotive aftermarket in Australia is the beneficiary of the first Right to Repair law in Australia, with a mandatory data sharing scheme for motor vehicle repairs coming into operation on 1 July 2022 which will go towards addressing the significant competition issues that have been experienced for many year in the motor vehicle repair industry.

To ensure better access to repair and service information, recommendations were also made to amend Australian copyright laws to facilitate the accessing and sharing of repair information (such repair manuals, and repair data hidden behind digital locks). Interestingly, in November 2021, Apple, sensing the pressure from the International Right to Repair movement, announced its Self-Repair programs through which it will offer parts, tools and manuals for consumer to repair their iPhones, although this will only apply in the first instance to iPhones 12 and 13s, so is not as broad as what the Productivity Commission has recommended.

Another key recommendation was to provide consumers with more information about a product’s repairability or durability at the point of sale, which would enable consumers to select more repairable and durable products based on their preferences. It was recommended that a product labelling scheme for white goods and consumer electronics products should be introduced in conjunction with industry, that provides repairability and/or durability information for consumers. This is in line with the recent development and implementation of the French Repairability Index. Importantly, the role that repairability can play in reducing EWaste was also reinforced with recommendations around improvements in product stewardship schemes which can help improve the way products are managed over their life, to reduce e-waste ending up in landfill.

While some Right to Repair advocates are disappointed that the Productivity Commission failed to recommend a broad all-encompassing Australian Right to Repair, the Inquiry and its recommendations have achieved a ground-swell of support from the Right to Repair movement in Australia. There is much work that we all can do to keep our goods from unnecessarily going into landfill. There are 70 Repair Cafes in Australia now with more being established every month. These Repair Cafes are manned by passionate repair volunteers and are playing an important role in educating others of the benefits of repairing and reusing our goods. We can all make a difference to a more environmental and sustainable future by making the simple decision to reduce our consumption and by starting with fixing our stuff.

Griffith University and the Law Futures Centre is hosting Repair Australia, which brings together a wide range of stakeholders interested in or working in the repair sector, who genuinely want to engage in open and respectful dialogue; with industry, other sectors and the community at large about the legislative and policy changes that are being developed to respond to the international right to repair movement.

The Law Futures Centre has sponsored and hosted a series of Right to Repair events.

On the 5th and 6th February 2020, a two day international academic workshop with Professor Taina Pihlajarinne, Faculty of Law and Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS) Finland and Professor Leah Grinvald, Suffolk University, Boston Massachusetts and Professor Graeme Austin from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, who were able to provide a European, United States and New Zealand perspective respectively. National intellectual property law experts also were in attendance, as were scholars and experts in the Repair movement from private enterprise/community organisations. This was a fascinating and innovative topic for an academic workshop and there was excellent discussion and engagement by participants.

A public Panel event on the Right to Repair was also organised and held on the evening of Wednesday 5th February at the Southbank campus, which featured a panel of 6 experts (including our International visiting academics) to which the public was invited. Professor Leanne Wiseman facilitated an open and intriguing discussion among the panellists and the audience. The forum was well attended and members of the audience were very engaged with the panel and the topic. If you missed the event, the recording can be found here.

In October 2020, a Building Back Better: Reuse, Repair and Recycle workshop was held at the Ship Inn, Southbank Campus which was also sponsored by the Law Futures Centre. This provided an opportunity for Reuse, Repair and Recycle stakeholders to meet and to exchange experiences, challenges and ideas. A network of Reuse, Repair and Recycle stakeholders was developed which provides important opportunities for collaboration. In April 2022, a hybrid in person and online Repair Café Networking event will be held at the Ship Inn, Southbank Campus to enable further collaboration in the Repair Café movement in Australia.

Recent Comments