This post has been contributed by Professor Charles Sampford, Director of The Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law (IEGL) and member of the Law Futures Centre

It would seem that we are facing no less than a national integrity crisis in which the routine abuse of power, the rejection of ethical standards and the undermining of integrity agencies is commonplace. This is leading to a self-perpetuating downward spiral in which unprincipled behaviour secures re-election and further reduces voter trust and hope.

Integrity reform is absolutely necessary. But it is entirely possible. It can and will happen if voters are so sick of the abuses that they demand ‘Integrity Now’ and political success is dependent on effective integrity reforms. Australia has a proud history of integrity reforms from the secret ballot and universal suffrage to the comprehensive post-Fitzgerald reforms in Queensland.

In considering how Australians should respond to this crisis, it is worthwhile comparing how two states responded to their own integrity crises in 1989. Nick Greiner won the NSW election in 1988 and followed the Hong Kong model which was then considered best practice anti-corruption reform. That model involved a strong anti-corruption law and, to enforce it, a strong Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) with permanent royal commission powers.

At the same time Greiner was establishing ICAC, Queensland awaited the report from what was possibly the most dramatic and influential Commission of Inquiry in Australia’s history – the Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct (the “Fitzgerald Inquiry”). Following shocking revelations in public hearings, the two major parties were attempting to outdo each other in promises to fully implement its recommendations, torturing their thesauruses to find ways to circumvent the mathematical inevitability that there is no way to go beyond 100 per cent. Queenslanders were keen to find out what had gone wrong. But they were also very keen to find out what Commissioner Fitzgerald thought they should do about it. And it was in the latter that he achieved the most lasting influence locally and internationally. He did recommend an ICAC (called variously the Criminal Justice Commission, the Crime and Misconduct Commission and, more recently, the Crime and Corruption Commission). But he did not think Queensland should rely on anti-corruption laws and institutions alone. Many other complementary reforms were needed. But he did not set out to prescribe them. He did not claim to have all the answers. But he had a very good idea of what the governance questions were and a process for answering them. He recommended a process of reform that has not been bettered in any other jurisdiction. That governance reform process was led by an independent Electoral and Administrative Review Commission (EARC). On each of 27 different issues, EARC (a) did an in depth study with the assistance of expert consultants; (b) published an issues paper: (c) called for public submissions and held public seminars and hearings; (d) responded to public submissions; (e) produced a final report to parliament with its recommendations resulting in the formation of a parliamentary committee which received further submissions and sometimes commissioned further papers and delivered its own report to parliament before the normal legislative process began. While it was appropriate for the Parliament to form its own conclusions, the recognition by all major parties that reform was necessary, the quality of EARC’s work and the inclusiveness of the process meant that most of the proposals were accepted. EARC also had the benefit of looking at the whole system of governance in Queensland and could understand the way existing institutions operated and how new ones might fit. By examining all the relevant institutions they could better understand how each interacted with the others. The result was an integrated set of norms, laws and institutions that would improve the governance of Queensland, promote integrity and reduce corruption. Because of the strong ethical foundation and the prominence given to public sector ethics, I called it an ethics regime in 1991. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopted the idea but changed the name to “ethics infrastructure” in 1996. Jeremy Pope, the first CEO of Transparency International visited Australia and saw the same benefits in the approach and called it an “integrity system” in 1997. Under these various names the multi-institutional approach has become the new gold standard for governance reform.

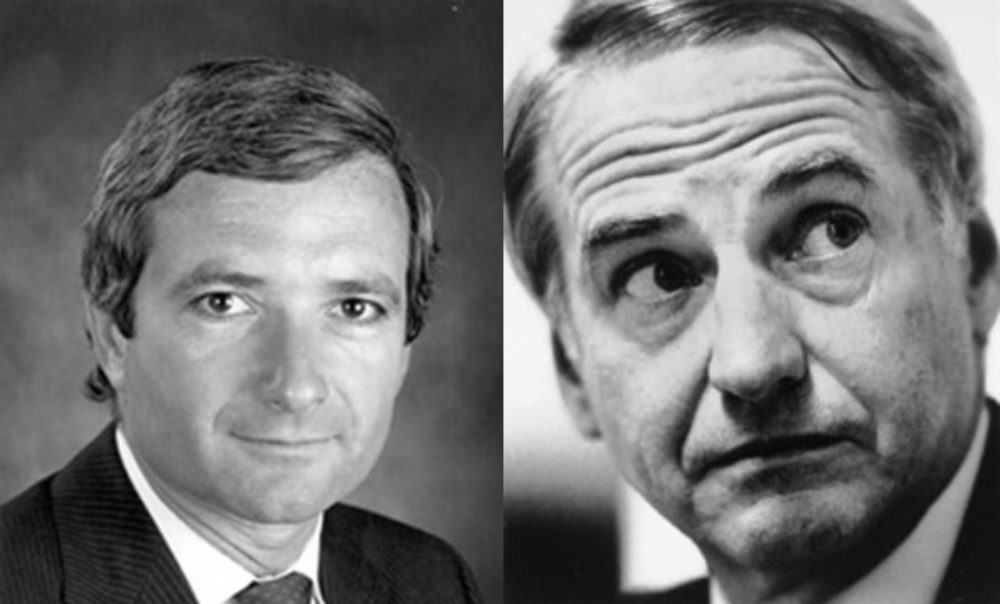

The Accountability Round Table (ART) https://www.accountabilityrt.org/ is an Australian NGO dedicated to improving standards of accountability, transparency, ethical behaviour and democratic practice. It is particularly concerned about the integrity crisis and the decline of public trust. ART has given strong support to an effective ICAC style Commonwealth Integrity Commission. However, such a CIC/ICAC is a necessary but not sufficient reform. Inspired by the systematic approach to governance reform that Fitzgerald and EARC, ART wondered what would be on a Fitzgerald style list of reforms to address the national integrity crisis and turn the national government into a global exemplar of good governance. ART has developed a strategy for reform fashioned by a reference group comprising former politicians from all sides of politics (including Barry Jones, John Hewson and Lynn Alison), former judges and civil servants (including Stephen Charles and Stuart Hamilton) and senior academics with extensive parliamentary or governmental experience. I had the privilege to be the Lead author.

The reform program starts by setting out some key guiding principles that are much used but less understood.

- The Rule of Law,

- Accountability and

- The Public Trust

It links these concepts to each other and to an understanding of Integrity and its opposite Corruption. All these centre on the need for elected and appointed officials to exercise the powers that are entrusted to them by the Australian people for the Australian people and not for themselves or their parties.

This paper sets out 21 recommendations for reform. Each sets out a problem to be addressed and the means of addressing them.

These include a strong and independent Commonwealth Integrity Commission (CIC). As indicated, such a body is necessary but insufficient. A CIC must be accompanied by other well-funded independent integrity agencies and anti-corruption measures – an integrity system. This has a number of recognized advantages: (a) they focus on promoting integrity, not just preventing corruption; (b) they are mutually supportive when performing their functions but mutually check each other if they exceed their powers and (c) it means that the CIC does not have to do all the work – or have all the power.

Seven of ART’s proposed reforms (1-7) make government more accountable to parliament which must be at the heart of the integrity system. These include oversight of: delegated legislation, treaties, spending, going to war, improving question time, committee resources and accountability of ministerial staff

Another 8 reforms (8-15) help parliament make government accountable: the CIC, non-partisan appointments, assessment of integrity risks, restoring judicial review, right to know, judicial commission, and guaranteed funding.

Five reforms increase the accountability of politicians (16-20). Enforcing a ministerial code; addressing truth in politics, money in politics, media reform, and preventing government’s abuse of its power to get re-elected (pork barrelling, voter suppression, election timing)

The remainder of the paper sets out the mechanisms for securing these reforms, highlighting the 21st recommendation – an EARC style Governance reform commission – the “lesson not learned” from the Fitzgerald reforms.

The paper was developed in September and October 2021 and launched in December 2021. By the time we had finished it, the need for an effective CIC was as clear as ever. However, recent events have also demonstrated the need for many of the other reforms.

- Exemption of delegated legislation from parliamentary scrutiny: reaching 599 pandemic related orders since the start of the pandemic

- treaties, AUKUS is apparently a done deal without any parliamentary scrutiny

- spending,Parliamentary control of spending continues to be eroded

- going to war: as a matter of politics, the PM decides if we go to war. As a matter of law it happens when the Defence Minister issues instructions to the Chief of the Defence Force and the Departmental secretary. There is talk of war over Taiwan and a minister who cannot conceive of us not joining in if the US decides to do so – a limitation of conception from which neither Menzies and Downer suffered.

- question time, improvements under former Speaker Smith are at risk

- committee resources parliamentary committees continue to do good work but the need for more resources continues

- ministerial staff are as unaccountable to parliament as ever

- non-partisan appointments, appointment of yet another Liberal politician to the Human Rights Commission

- assessment of integrity risks: the risks of leaving huge spending subject to ministerial discretion are being exploited rather than recognized and constrained.

- restoring judicial review is not on this government’s agenda

- FOI and right to know are deliberately undermined by the attempt to treat ‘national cabinet’ as if it were part of the federal cabinet

- judicial commission: judicial appointments continue to be made on the unexamined whims of the PM and his cabinet

- guaranteed funding of integrity agencies is not provided. Indeed institutions with a critical role in political accountability have their funding reduced when they perform that role too well (e.g. the ABC and the Auditor-General)

- Enforcing the ministerial code; the Prime Minister continues to be the sole arbiter of whether ministers breach the ministerial code – including the clear responsibility of ministers who lie or mislead. A PM is fundamentally and irredeemably conflicted in dealing with alleged breaches of his colleagues and even more with alleged breaches by himself. The current PM has gone further in preventing the Privileges Committee from considering an alleged breach of parliamentary disclosure rules – a breach for which the former speaker considered a prima facie case had been made.

- truth in politics continues to be trashed with numerous non-exhaustive lists of lies told and a willingness to deny what is on the face of the public record. There is bi-partisan agreement that lying is rampant – the ALP says LNP ministers lie, the LNP says ALP shadow ministers lie, most of the cross bench think they are both right!

- money in politics Michael Yabsley’s revelations on funding are shocking, even for the previously cynical. Clive Palmer’s advertisements offend us from every commercial channel.

- media reform, consists in boosting our shamefully concentrated private media and attempts to undermine the ABC. The idea of encouraging oligopolists to negotiate behind closed doors arrangements that suit themselves would make Adam Smith spin in his grave. We now know that tens of millions have been transferred – without any commitment to fund journalism (or pay taxes)

- preventing government’s abuse of its power to get re-elected: pork barrelling remains rife with indications of a bumper season. Proposed ID laws are seeking to introduce US style voter suppression. And, as usual, the government is considering what election timing will suit it. Government advertising of its climate change credentials provide spin not information.

- governance reform commission (modelled on EARC): the necessity for a specialized commission to evaluate, co-ordinate and recommend integrity reforms was demonstrated through the Fitzgerald reform process and is all the more needed because of the misleading claims about proposed reforms and the absence of any others.

The reform package is available at https://www.accountabilityrt.org/integrity-now-download-the-document/ Comments and suggestions are most welcome.

Recent Comments