PAUL SLATER |

In 1999, tensions between ethnic groups in Solomon Islands were rising. For anyone who cared to notice, there was even a resemblance to the tensions 11years earlier, on neighbouring Bougainville, in the lead up to the crisis which gripped and tore apart that island for the next ten years. The Solomon Islands Prime Minister in 1999, Bart Ulufa’alu, asked Australia for help. He characterised Australia’s words in response to his plea for help as being like a man standing on the shore reading to a drowning man from a lifesaving manual. Only after the tensions had turned to bloody violence did Australia act, spending over $2.6 Billion between 2003 and 2017 on “Operation Helpem Fren,” also known as the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).

Despite Australia’s geographic proximity and colonial history in the region, hard won victories in the Second World War and lessons that should have been learned from Bougainville, the Australian Government seemed incapable of understanding what was happening in 1999 Solomon Islands and why Bart Ulufa’alu was rightly worried. Australians knew more about America, Asia, Europe or the Middle East and the people of those places than they did about their closest neighbours in the Pacific. That has not changed since 1999.

The current Prime Minister, Manasseh Sogavare, is not new to the job or the relationship with Australia. This is the fourth time he has been Prime Minister. The first was in 2000, when rebels from the Malaitan Eagle Force captured Ulufa’alu and forced him to resign. During the past 22 years there has been ample opportunity for Australian politicians, in and out of government, to build relationships with their counterparts in Solomon Islands and elsewhere in the Pacific, including Sogavare, as difficult as that may have been.

In 2020, in The Pacific Step-up: it’s the way that you do it , I talked about the necessity of authentic personal relationships for anyone or any country, including Australia, to have influence in the Pacific. I provided examples of how Australians have successfully done this in the past. I talk about the importance of spending time with people in the Pacific as a culturally meaningful reciprocity at the heart of authentic relationships.

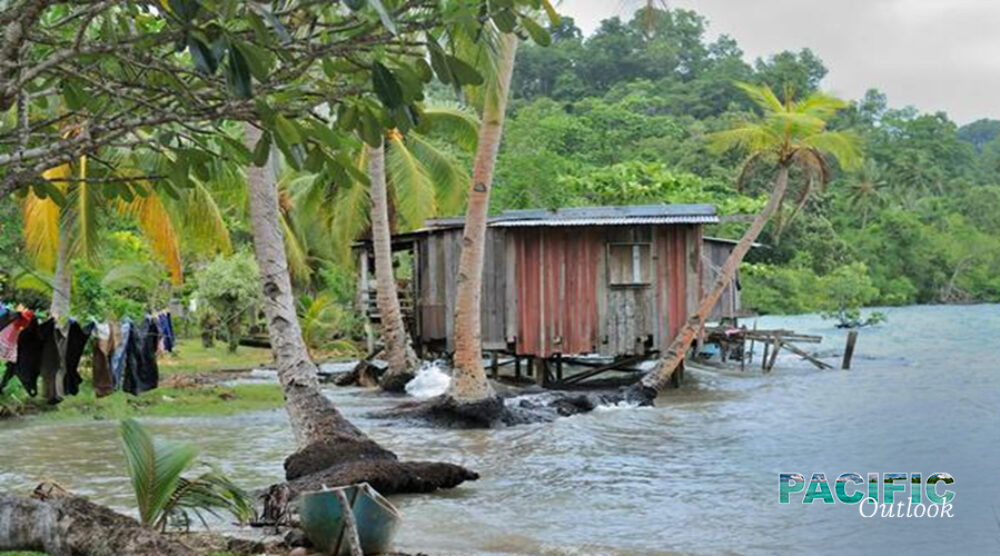

Those relationships can’t be formed at the drop of a hat with flying visits by senior officials or politicians when we perceive a crisis. Especially if we have at times treated Pacific countries’ concerns about issues like climate change and drowning islands with what many in the Pacific perceive as disrespect.

Australia’s and other countries’ reaction to the 2022 security agreement between Solomon Islands and China is a case in point. Seeing the agreement as a threat to Australia’s strategic interests, the Australian Government first despatched two senior intelligence officials and then the junior Minister for the Pacific, Zed Seselja, to the Solomon Islands’ capital, Honiara. Presumably, their mission was to dissuade the Solomon Islands Government from proceeding with the agreement. The United States followed suit with a visit by the White House Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific, Kurt Campbell, and entourage.

That these envoys were received and heard in Honiara could be seen as evidence of Australian and United States ability to exercise soft power in the Pacific; our good relationships with this Pacific nation had provided us with valuable access. According to our rules, that is the way it is supposed to work, after all, we provide lots of aid, don’t we?

The envoys were undoubtedly politely, even respectfully received, but the despatch of fly-in fly-out envoys with little or no personal involvement with the country, its leaders and its people is more likely to have been seen as a disrespectful. And Prime Minister Sogavare does not appear to have been dissuaded. Seeing soft power in the Pacific in terms of a quantum of aid or in terms of the rules by which we conduct our strategic relations elsewhere is not always effective.

There is an old adage of diplomacy, attributed to mid-19th Century British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, that countries don’t have friends, they only have interests. That formulation sits well with our Western rules-based-order approach to international relations. Perhaps we need to see our relationships with Pacific countries, where the rules might not be the same, a bit more like friendships. We can still strive to advance our interests, but read a little less from the lifesaving manual.

Paul Slater is a former Pacific desk officer in the Defence, Liaison Office in Papua New Guinea, and Bougainville Peacekeeper.