The United Nations human rights committee, who heard the case between Teitiota v New Zealand in January, obfuscated Teitiota’s argument on human rights when they declared his case a landmark ruling towards a pathway for climate refugees in the future. This is not what Teititoa argued for when he took his case to the UNHRC and lost. He claimed that due to sea level rising and continuous sea coastal flooding, the lack of access to safe, potable water and sanitation was a threat to his right to life.

Somewhere between New Zealand, Geneva and the rest of the world, the message from the UN experts about non-refoulment of climate refugees became all about how this case was going to change the approach between governments and people seeking refugee status from climate crisis. Teitiota’s case was based on the substantive elements in Article 6 (1), ‘Right to Life’ of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and not on any other substantive element pertaining to international refugee law. This would not have been admissible because the convention relating to the Status of Refugees does not provide protection to people seeking refuge from climate change and climate crisis disasters. Migration laws are created by national legislatures and governments have no obligation under international law to broaden their scope to cover people leaving their countries due to climate crisis.

According to media reports citing UN experts, the “landmark ruling” represents a “legal tipping point”. The Committee ruled that it would be unlawful for governments to return those seeking asylum to their countries if their lives are threatened by the impacts of climate change. However, the committee did not ask New Zealand to refrain from sending Teitiota and his family back to Kiribati whilst the decision was pending at the UNHRC. This enabled an administrative refoulment in spite of Teitiota’s case not having been settled.

The committee found that Teitiota’s reasons for his objections to his deportation to Kiribati were unfounded and did not meet the threshold of the threat to his life as he claimed. The UN human rights committee said that “ sea level rise is likely to render the republic of Kiribati uninhabitable…the timeframe of 10-15 years as suggested by Teitiota, could allow for intervening acts by the Republic of Kiribati, with the assistance of the international community, to take affirmative measures to protect and where necessary, relocate its population.”

The UN report by the Special Rapporteur for the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, mission to Kiribati, Catarina de Albuquerque, said that although the government of Kiribati had a national plan for safe water practices, these plans were far from being fully implemented and nor did the plans identify links between water sanitation and high infant and child mortality rates. Kiribati has no clean surface water.

In her dissenting opinion, UNHRC member, Vasilka Sancin, stated that it should have been the obligation of the state party (i.e. New Zealand) to demonstrate that Teitiota and his family would not be denied the right to enjoy safe drinking and potable water. She could not agree with the committee’s finding, referring also to the UN special rapporteur’s report and found in favour for Teitiota’s claim under Article 6 (1). She objected to the deportation of him and his family.

Ioane Teitiota’s case may be seen as a landmark case in the sense that it could very well be the first case tried as a climate refugee claim. However, as long as there is no refugee status permitted under international law for those seeking asylum due to climate and environmental disasters, then such cases are dead in the water. What does exist and has an established robust legal framework, is international human rights law. However, right now we are seeing the practice of human rights being diluted and weakened by world leaders, governments, and even by the very institutions that we look to as our last hope.

There is an unsettling trend in the failure to uphold human rights norms and moral principles.

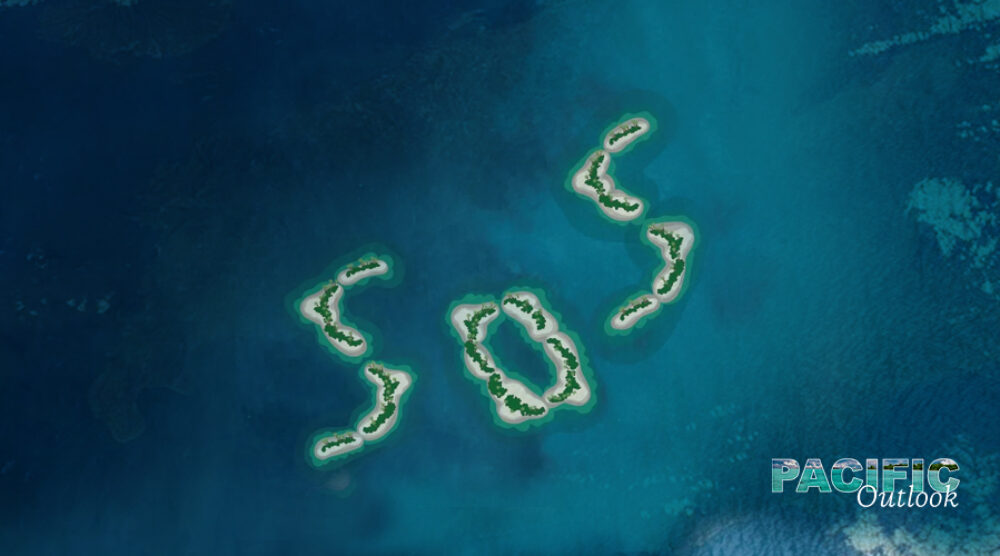

If we do not give human rights priority consideration when it comes to climate change, then we have not understood the emergency faced by those who are most vulnerable. The UNHRC decision in the Teitiota case could be seen as an indication that the committee has not understood the human rights crisis faced by some Pacific islanders as a direct result of climate change. The council does not seem to be on a climate emergency footing.

Assumptions of potential legal recourse but without any existing legal framework that can apply today means that the voices of Pacific people and communities whose human rights are impacted by climate change now, will be drowned out by the background noise.

Grace Maharaj was born in Fiji and grew up in New Zealand and is a resident of Sweden. She has worked with asylum and migration for the social services department under the municipality of Stockholm. She is currently studying Climate Change Leadership, Peace and Conflict Studies at the Uppsala University, Sweden.