EMILY HOUSE |

Our futures are constantly shaped by the past. But who is this future shaped for?

The future is often offered to us in exchange for the past. When we experience something unpleasant, the common line is to ‘look forward’ or ‘move on’, as a way of justifying and overcoming feelings of sadness or grief. Imagining oneself in the future is necessary for the human condition but it also taints the past, rendering it an obstacle to personal growth. Leaving the past behind in favour of what is to come is at the heart of the politics of development and state building. But who does this rhetoric actually benefit? Does the future need to be at odds with the past? What happens when your lived experience is not written into the future?

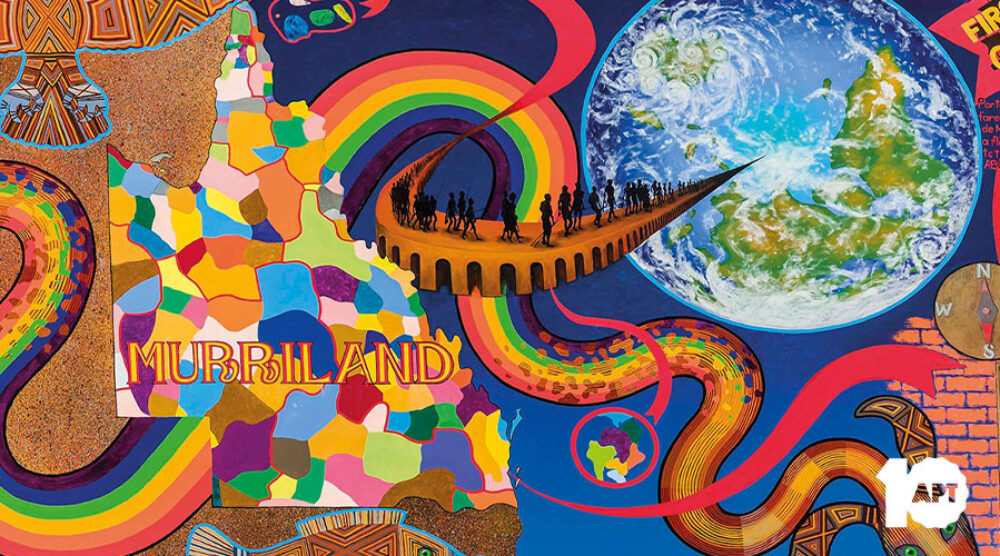

The final All A Part symposium dealt with questions of the future, specifically asking how we can reimagine a future that values the lives, experiences and cultures of First Nations groups across the Asia-Pacific region. Australia’s future, like much of the Asia Pacific, has been almost entirely imagined through the eyes of colonial figures. When fleeting imaginaries have encompassed First Nations culture, rarely – if ever – have visions of the future provided more than a glimpse of mere survival.

Ideas about development and progress have been at the forefront of colonial nationalist politics in Australia. The future that has been written through the lens of colonisation, has continually attempted to write First Nation’s people out of it. Denying their right to land, freedom and culture, often in favour of economic development. Not only have politicians repeatedly endeavoured to ‘move on’ and leave First Nation’s suffering in the past, but important cultural histories have been, and continue to be, destroyed. Subash Thebe Limbu is a Nepalese artist whose film, Ningwasum, is exhibited in ATP10, disputes dominant visions of the future; by imagining one in which First Nation’s people and cultures are at the forefront. The film’s sci-fi genre is the perfect platform for speculating about a future that delineates from typical classifications of the ‘futuristic’. Playing directly with ideas of time travel, we are presented with an alternate reality.

Perhaps the most striking quote from Ningwasum reads “I come from a future that you probably cannot imagine”. In this simple, yet powerful, line the very essence of the colonial past’s influence over how we can (and cannot) envision the future is captured. Subash Thebe Limbu brings this idea to life throughout Ningwasum, which embodies what he calls ‘Adivasi Futurism’. Adivasi (as the Nepalese word for Indigenous) futurism is a concept that builds off theories of Indigenous and Afro futurism to imagine a similar post-colonial and post-capitalist future, with a more localised focus on Indigenous people across the Indian sub-continent. Adivasi futurism becomes a transformative space where Indigenous artists and creators can manufacture the very futures that have, until now, been considered impossible.

The future imagined through Thebe Limbu’s lens contains both Indigenous traditions as well as technological advancements; two concepts that have, until now, only been imagined as contradictory. Thebe Limbu rejects post-modern aesthetics by imagining traditional Indigenous symbols as typically futuristic elements. For example, the film’s time-travel spaceships are in the shape of a Silamsakma, the symbolic identity of the Yakthung Indigenous nationalities in Nepal. This bridging of Indigenous pasts and the futures is a powerful suggestion of how things that have typically been condemned to the past can have a place in alternate futures. The film’s futuristic aesthetic has powerful capabilities to dismantle the binary that has kept Indigenous history, peoples and cultures labelled as ‘primitive’ and ‘anti-development’. It simultaneously presents a future in which both Indigenous people and culture are at the forefront. Ningwasum challenges dominate timelines that endeavour to forego the past, allowing us to take histories into the future; creating imaginations of possibility, where the past is not forgotten, and no future is impossible. Alternative futures that celebrate Indigenous storytelling, symbols and language in combination with technology and time travel, successfully redefine orthodox futurism.

Although Thebe Limbu’s film is fiction, its imaginary powers have real-world consequences. While our lives remain ruled by linear timelines of constant development, the coloniser, and all those who benefit from colonial ideals, remain privileged, while people and cultures who are seen as obstacles to development remain invisible. Thebe Limbu’s work in APT10 invites us to imagine a timeline created by Indigenous imaginaries, that values history, traditional symbols and culture. As one walks around the gallery space that the APT10 inhabits, they are invited into the myriad, non-linear timelines of Indigenous artists from all over the Asia Pacific.

Ningwasum does more than just present a future of survival, it puts Indigeneity at the forefront of futures, constantly reminding us that the answer to development is not the erasure of the past. Or in the words of Thebe Limbu:

“We [First Nations peoples] are not just the storytellers of the past, but we could also be the creators of interstellar civilisations of the future”.

We are reminded of the power of political imagination. Works that centre Indigenous lifeworlds rewrite narratives on agency, that have until now, proposed that Indigenous culture is passive- that it belongs in the past. But, by not forgetting the past, and by reimagining colonial timelines that have dominated cultural understandings of the future, Timbe Limbu offers alternate ideas to our linear progressions of time. Presenting a future that has hardly been imagined, one that embraces the past. The APT10—though its curation and display of works by the like of Thebe Limbu—has a significant part to play in creating new futures for the Asia Pacific region. A future that places First Nations peoples at its centre.

Emily House is an Honours graduate from Griffith University in the school of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences and a research assistant at the Griffith Asia Institute.

This article forms part of a series of commentary curated to reflect on the All A Part Symposium in celebration of the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial (ATP10), the landmark tenth edition of the exhibition.