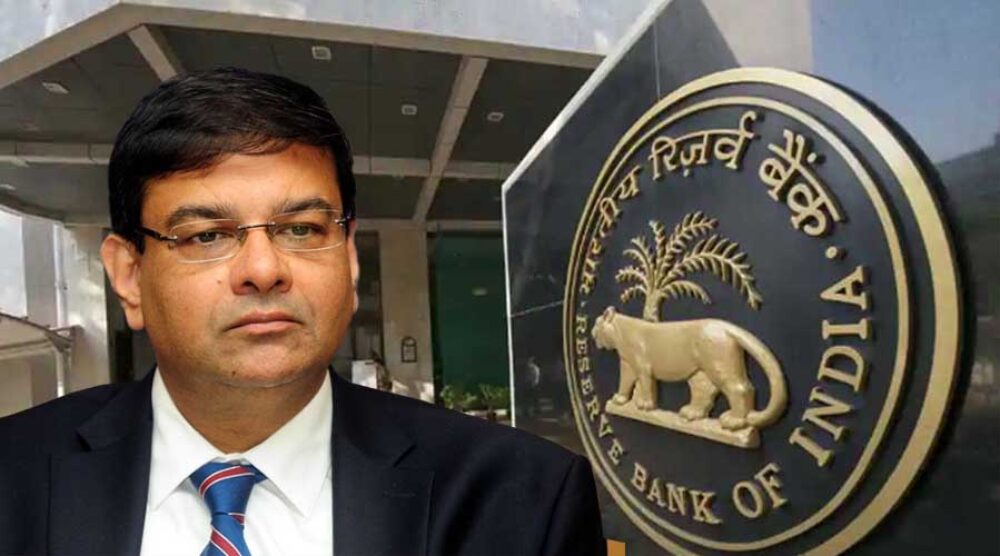

Urjit Patel, until very recently the 24th Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), could no longer maintain his customary reticence. He decided to resign on 10 December before his term was completed. He cited ‘personal reasons’ for his early exit, but it was clear that he was not able to manage or withstand the rift that opened up between him and his political masters. There were public disagreements on relaxing lending norms for small business and debt-distressed state banks and on the ability of the Indian government to have access to the RBI’s formidable financial largesse.

While Dr Patel was by no means the first RBI governor to quit before his term was over, he was certainly one of the very few to do so since the early 1990s. His predecessor Raghu Rajan chose not to seek a second term and went back to his academic habitat at Chicago. Rajan and Patel had a close intellectual alliance. When Urjit Patel was the Deputy Governor, he chaired a committee (widely known as the Urjit Patel Committee) that made the case for the RBI to adopt inflation targeting as a monetary policy regime. Rajan inaugurated that regime in his role as Governor, while Patel continued on this path with renewed vigour.

In his resignation note, Patel pointedly refused to acknowledge the support he received from Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley. The duo in turn struck a more magnanimous gesture, and in keeping with modern modes of communication, ‘tweeted’ their appreciation of Patel’s contribution to the RBI.

There were some wobbles in currency and bond markets in response to the sudden resignation of the RBI governor, but there is, as yet, no evidence of catastrophic outcomes as predicted by the Deputy Governor Viral Acharya. The government gave a metaphorical shrug of the shoulder and promptly appointed Shaktikanta Das, a former senior civil servant, to head the RBI and reset its apparently troubled relationship with the government. Mr Das is seen as a ‘loyalist’. It was he, rather than Patel, who managed the disruptive process of demonetisation in its early days.

Media commentators are largely united in their views that Patel’s resignation signifies a serious threat to central bank autonomy in India. It is considered an article of faith among many that central bank independence is crucial for price stability. Such a view was largely formed on the basis of some influential academic research in the early 1990s, but such research has been subjected to considerable critical scrutiny.

Central bank autonomy is one possible factor that influences economic performance. Giving too much power and authority to central banks might end up being counter-productive, as a former central banker has argued. Not surprisingly, the desirability of central bank autonomy has been questioned by some leading economists, such as Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz. Furthermore, in an age of low inflation and sluggish growth, central banks need to think beyond their narrow remit of safeguarding price stability. This is perhaps one reason why the central bank of New Zealand that pioneered inflation targeting is now poised to broaden its mandate to include ‘employment alongside price stability’ as one of its primary goals. The RBI under Patel’s leadership does not necessarily have an impeccable record. It has been conspicuous in overestimating the expected inflation rate and thus appeared to be more hawkish than was warranted. In any case, as a veteran Indian journalist argues, Patel’s resignation probably reflects the personal aptitude and characteristics of an individual rather than an existential struggle over the future role of an institution. Patel allowed himself to become an unwitting accomplice in the government’s demonetisation debacle. He was considered to be an insufficiently skilled communicator and dogmatic in his approach to policy-making. Perhaps he committed the sin of overlooking the fact that ultimately the Indian government is the ‘owner of the Reserve Bank’.

Iyanatul Islam is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute and former Branch Chief, ILO, Geneva.