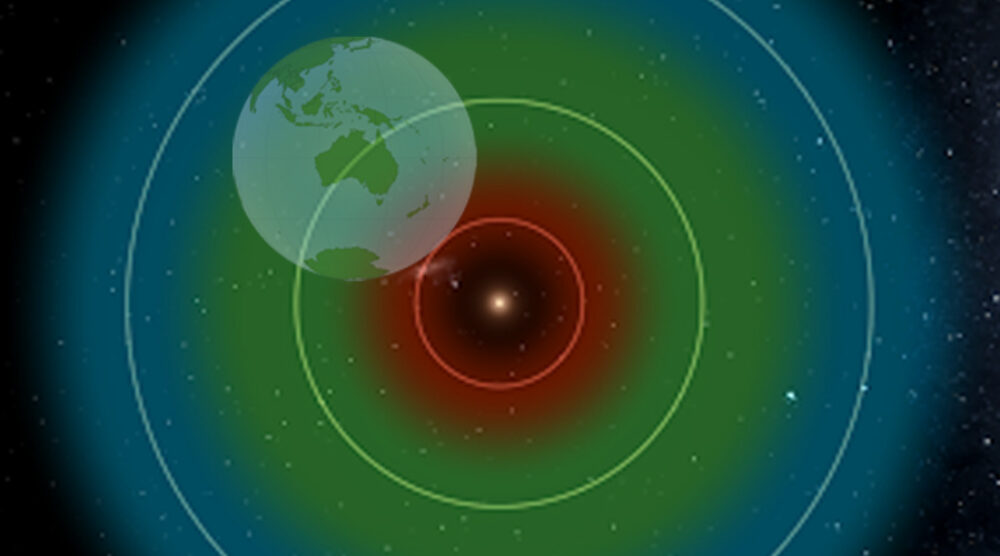

In science it is noted that terrestrial planets are situated in the ‘Goldilocks zone’, that is the habitable or life zone in space where a planet is just the ‘right distance from a home star so that’s its surface is neither too hot nor too cold.’ The Goldilocks zone in a galaxy thus allows life to develop and flourish. For decades the Australia-Philippines strategic relationship has been characterised by missed opportunities and strategic inertia. When the bilateral relationship has developed it has generally been through by slow incremental engagement that, at times, has easily and quickly gone cold. However, the recent the terrorist attack on Marawi in the southern Philippines has injected new energy into the strategic dimensions of this bilateral relationship. Marawi along with changing regional dynamics has potentially opened up a ‘goldilocks zone’ movement in the Australia-Philippines strategic relationship: one in which the partnership could develop and flourish. The ability to capitalise on this recent rapid progress could though still easily stagnate especially as domestic politics in the Philippines could easily get too hot, burning the burgeoning relationship or Australia could easily become distracted from its engagement letting the pace of progress stagnate or go cold. This means that the window of opportunity to cement a much deeper and more coherent bilateral partnership remains narrow. If not seized quickly this opportunity could easily prove to be fleeting.

Missed opportunities and strategic inertia

The history of the Australia-Philippines bilateral security partnership has been one characterised by most of long periods of strategic inertia and missed opportunities dating as far back as the Pacific War. Interestingly two key bookends of missed opportunities came as a result of our mutual major power ally, the United States. During the Pacific War both the Philippines and Australia fell into a geographic command called the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) under the leadership of the infamous US general, Douglas MacArthur. In 1942-44 MacArthur’s Headquarters was in Australia, which also briefly included the Philippines Government in exile (March-April 1942) when the President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, Manuel L. Quezon, and his family arrived in Australia from the Philippines, before transferring to the USA.

MacArthur’s triumphant return to the Philippines in 1944-45 was off the back of coalition operations in the SWPA where the Australian military formed a significant part of MacArthur’s forces fighting in Papua, New Guinea and the surrounding islands. In 1944 the strike force of the Australian Army, its three elite Australian Imperial Force Divisions (AIF), were poised to take part in the liberation of the Philippines, but by now the overwhelming preponderance of US military forces in the theatre meant that MacArthur was able to sideline Australia’s efforts in his theatre in 1944-45, shunting the AIF division off to an irrelevant campaign in Borneo instead of fighting in one of the decisive action of the war.

This is not to say that Australia’s contribution to the liberation of the Philippines was not significant. The battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944 remains the biggest ever operation of the Royal Australian Navy, and some 4,000 Australia’s took part in these operations, but the absence of large scale Australian land forces in the battles for Leyte and Luzon as meant that the bonds of kinship forged in war were not developed between Australian and the Philippines, nor is there the same sense of shared sacrifice to bond the two nations militaries in the same way as Australia developed with other countries who hold significant the sites of war memory, history and pilgrimage from Australia’s military campaigns. Some 70 years later the developing Australia-Philippines relations was also truncated by the onset of the Global War on Terror (GWOT). The GWOT saw a significant reinvigoration of the US-Philippines defence relationship which led to a decreased in Australia-Philippine bi lateral defence engagements as both smaller power sort to revaluate and refocus their relationship with their major power ally.

This focus by both countries on their strategic relationship with their major power ally is emblematic of how the security architecture of Asia was established in the post-Second War World era. With Japanese military power crushed in 1944-45 the US emerged as the hegemony of the region and with the onset of the Cold War it solidified its regional defence engagements through the San Francisco system of alliances. This network, known as the hubs and spokes alliance system, placed the USA at the epicentre of a series of bilateral and trilateral alliance agreements, which encouraged little engagement between the spokes.

A new multilateral defence alliance system did, however, emerge with the Manila Pact. Signed in September 1954 the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was the regional hope for a multilateral alliance network in Asia to replicate the success of NATO in Europe. This alliance framework provided the opportunity for the Australia-Philippine defence relationship to develop, however SEATO would prove to be largely ineffectual. At the heart of SEATO lay a number of fundamental differences to NATO, the two most significant being: the lack of an Article 5 provision like NATO, where an attack on one member of NATO is an attack on all of its members; and the fact that the majority of countries in the Pact (USA, United Kingdom, France, Pakistan, Australia, New Zealand, Philippines and Thailand) were not actually Southeast Asian. This meant that in many sense SEATO was not unlike Voltaire’s characterisation of the Holy Roman Empire, which he saw as neither Holy nor Roman, nor in fact an Empire; conversely SEATO was not really an alliance, was not really SE Asian and in the end not much of an organisation. Even worse SEATO was described by the diplomat James Cable as ‘a fig leaf for the nakedness of American policy.’ In the end the alliance pact was put out of its misery in 1977.

While SEATO provide the premise for US engagement in the Vietnam War it was the hubs and spokes system alliances that were the key security relationships that kept the US engaged in Asia. With the Nixon Doctrine announced in 1969, which called for more defence self-reliance and prefixed the US withdrawal from Vietnam, and the SEATO falling apart the Australia-Philippines security relationship became a moribund relationship until the mid 1990s.

A new era in the Australia-Philippines relations emerged in the post-Cold War era. This was kicked off by the 1994 trade agreement followed by the 1995 MOU on defence cooperation. From here a slow trajectory of Australia-Philippines security engagements started to emerge including the establishment of a joint defence cooperation committee, and a significant expansion of the Australian defence cooperation program which saw Australia emerge as the major provider of education and training to Filipino military, which includes approximately 150 positions offered annually for training in Australia. As mentioned, the momentum of this cooperation however stalled in the early 2000s as the ‘reinvigoration of the Philippine-American defence relations[ship]…diminished Canberra’s role in Philippine defence diplomacy.’

New opportunities

While momentum stalled in the GWOT bi-lateral efforts at engagement did not stop all together. Track II dialogues continued to develop and regular talks at the Track 1 level were established with the Philippines-Australia Ministerial Meeting (PAMM) and its Senior Officials Meeting (SOM), Philippine-Australia Bilateral Counter-Terrorism Consultations (BCTC), High Level Consultations on Development Cooperation (HLC), and Joint Defence Cooperation Committee (JDCC) and Defence Cooperation Working Group (DCWG) talks. Thereafter the US pivot, later rebalance, to Asia, under the Obama Administration spurred on by changing regional dynamics, as well as the transfer of Australian military equipment to the Philippines, mutual defence and security interests, and increased multilateral engagements have all driven closer cooperation between Australia and the Philippines.

Defence relations really accelerated with the occupation of Marwari in May 2017, a city of approximately 200,000 people (roughly equal to the size of the Australian cities of Hobart, Geelong or Townsville) on the southern islands of Mindanao by between 1,000-2,000 Islamic terrorists who pledged allegiance to ISIL. Australian support of the Philippines included P3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft that provided intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance support and well as advisors and maritime support. In Mid October 2017 the Australian Defence Force established Joint Task Force Group 629 to execute Operation Augury which includes the deployment of ‘around 100 ADF personnel’ on deployment to the Philippines’ for a broad range of engagement including an urban warfare training program.

While the operations in Marwari were successful, at the cost of the deaths of 920 Islamic fighters, 165 government soldiers and at least 45 civilians, as Samuel Cox has noted ‘the key message for Australian policymakers is that we can expect more Marawis in our region. The risk to regional stability posed by Islamic State’s goal of creating a ‘caliphate’ in Southeast Asia has by no means passed, and the urban conditions which led to this conflict remain widespread.’

New opportunities and risks

While opportunities now abound for deeper cooperation there remains a number of potential risks to developing deeper ties, in particular domestic politics. In the Philippines the unpredictability of President Rodrigo Duterte, concerns over human rights abuses – highlighted by the UN Human Rights Council censure and investigation of the Philippines over the thousands of killings since President Rodrigo Duterte launched an anti-drug campaign (including Australian support for the resolution) – presents a clear risk to closer ties. In Australia this was highlighted over the media controversy surrounding the picture of President Duterte with senior Australian intelligence official Nick Warner and concerns over the ‘dark’ nature of Australian military support for the Philippines in the post Marwari era.

In Australia the Morrison Governments’ election surprised almost everyone, expect perhaps for the Prime Minister. Thus, the Liberal-National Coalition has come to power short on a broad political agenda, with relatively new leadership in foreign affairs and defence, and rising concerns on Australia’s doorstep in the south Pacific. President Trump has called only his second State Dinner for the planned trip of the Australian Prime Minister to Washington in September. This high level engagement, security concerns about China’s influence in Australia’s backyard in the South Pacific and continued tension in the Middle East, which recently saw the extension of the deployment of a KC-30A air-to-air refuelling aircraft to the Australian Defence Force Air Task Group and redeployment of an E-7A Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft support US-led Coalition operations until late 2020, are all risks. In particular the high-level strategic engagement with the Trump administration in September as well as the continued Australian military engagement in the Middle East with the US – a large opportunity cost for a small military – could well lead to Australian political attention, and defence resources, moving away from its posture of a deeper engagement in the Philippines.

The conflation of changing Asian regional dynamics, a focus in both the Philippines and Australian on broader regional engagement and the turbo charge to the defence relationship from the highly successful interactions in support of the conflict in Marawi seem to have created the ‘goldilocks’ moment for Philippines-Australia. However, as the past has indicated the foundations to deep and ongoing relations have still not been set in concrete. Tangible progress, like an upgrading the relationship to a ‘strategic partisanship’, providing for long term defence engagement across a broad spectrum of operations from maritime security to urban warfare operations are critical, however it could well prove that the window for setting the conditions of lasting engagement in the Philippine-Australia relationship could close quickly leavening the porridge cold and setting off another era of missed opportunities.

Peter Dean, University of Western Australia Defence and Security Program

This commentary is based on the discussions in the Philippine-Australia Dialogue, jointly organised by the Asia Pacific Pathways to Progress and the Griffith Asia Institute, and with the support of the Australian Embassy in Manila.